Kathleen McPhillips, University of Newcastle

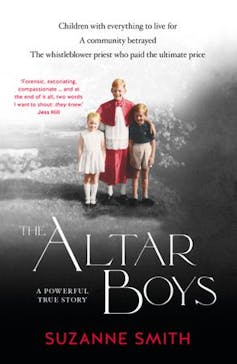

Investigative journalist Suzie Smith’s new book The Altar Boys is a searing read that raises new questions about the suicides of three former victims of Catholic clergy child sexual abuse.

Smith, a former award-winning ABC journalist, has been covering the clerical abuse crisis in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese for many years. She wrote the book in part to bring new attention to the three victims, whose suicides remain shrouded in mystery, despite two public inquiries.

The Altar Boys recounts the lives — and deaths — of Glen Walsh, Steven Alward and Andrew Nash. All three of them were victims of child sexual abuse by Catholic clerics in the diocese.

Andrew Nash was just 13 years old when he committed suicide in 1974 after being sexually abused at St. Francis Xavier College in Hamilton, NSW. Andrew was in the care of two Marist Brothers who have since been convicted on child sex offences.

Walsh committed suicide in 2017, just weeks before he was due to give evidence at the trial of Archbishop Philip Wilson. Wilson had been charged with failing to report to police that paedophile priest James Fletcher was abusing boys in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese. He was convicted in 2018, but was set free after the judgement was quashed.

And Steven Alward, a respected ABC journalist and close friend of Smith’s, took his own life shortly after Walsh, in January 2018.

Both Walsh and Alward grew up together in Newcastle and were altar boys at the local Catholic church. They were also victims of child sexual abuse.

According to the book, Alward told his brother he was abused by notorious paedophile priest John Denham at St. Pius X High School in Adamstown. Smith details how Walsh was allegedly abused by Marist Brother Coman Sykes while he was staying at a Marist brothers-owned house west of Sydney.

Calls for new inquiry into the death of Glen Walsh

This area of New South Wales is recognised as one of the epicentres of clerical abuse in Australia, along with Wollongong and Ballarat in Victoria.

Since the Wood Royal Commission investigated paedophilia in this area in the 1990s, there have been numerous police task forces and two public inquiries into child sex abuse — the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry and the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse. The royal commission held public hearings in the Maitland-Newcastle region for over a month in 2016.

Smith’s book sheds new light on the institutional child sexual abuse and alleged cover-ups in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese, especially related to the treatment of the whistleblower priest Glen Walsh.

Last week, NSW Greens MP David Shoebridge called for an urgent judicial inquiry into Walsh’s suicide and the events leading up to the tragedy.

A letter from Bishop Bill Wright to the Catholic community in response, however, said church leaders see no reason to investigate these matters further as they are “historical” and have been addressed by previous inquiries.

The story of Walsh’s decline and suicide

In her book, Smith details what happened in Walsh’s life after his abuse, when he became a priest himself in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese.

In 2004, Walsh was sent to work in the upper Hunter parishes of Branxton/Greta to take over following the arrest of Fletcher on child sex abuse charges.

When two young men told Walsh about being abused by Fletcher, Walsh defied church practice and reported the matters to the police, including detective sergeant Peter Fox. Fox’s explosive allegations about the links between the police and Catholic clergy in the diocese would later spark the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry.

Read more: The Catholic Church is headed for another sex abuse scandal as #NunsToo speak up

By taking this action, Walsh was ostracised and banished from the diocese. Smith recounts how his health deteriorated and he became homeless, asking to return to the diocese on numerous occasions. He finally got his wish in 2017 when Wright invited Walsh back to Newcastle.

After Wilson, the archbishop, was charged with covering up child sex abuse, Walsh became a key witness for the prosecution.

Smith describes an episode - until now not public knowledge - where prior to Wilson’s court case, Walsh was called to Rome for a private interview with Pope Francis. The pope reportedly wanted to know what Walsh would say in court, as Cardinal George Pell waited for him outside the room.

Just weeks before he was due to give evidence, Walsh took his own life.

He was vindicated during the trial when Magistrate Robert Stone found Walsh had in fact telephoned Wilson in 2004 and reported the child sexual abuse inflicted by Fletcher on numerous boys.

Questions still need to be answered

There are many unanswered questions about the deaths of all three victims. Importantly, Smith also links these deaths to the issue of ongoing suicides and sudden deaths among survivors of alleged child sex abuse in the Maitland-Newcastle area.

The Clergy Abused Network, a regional support group for survivors and their families, has kept a register of deaths by suspected suicide — the number now totals over 60.

To continue to frame this issue as “historical”, as Bishop Wright did in his letter, is problematic and harmful and ignores the ongoing tragedy of suicides in this region. This issue is hardly historical — it is happening now.

Read more: Royal commission hearings show Catholic Church faces a massive reform task

If there is further evidence, as Smith’s book suggests, of failure by Catholic officials in the investigation of suspected child sex abuse cases, then another judicial inquiry is justified.

What has compounded the trauma for survivors and their families that the findings of the Child Abuse Royal Commission’s case study 43, which examined child sexual abuse in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese, have yet to be released.

Survivors and their families should have access to the final report, which continues to be withheld. They deserve to see if it contains more answers to these tragedies.![]()

Kathleen McPhillips, Senior Lecturer, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.