The biblical Christmas story, the one that announces the birth of Jesus, seems so sweet it can appear almost saccharine. It is so often told as a children’s story and a sentimental one at that.

Yet it is deeply political and has been from the beginning. The oldest extant texts to record the birth of Jesus go out of their way to locate him in his political setting. Moreover, they portray him as a threat to that empire.

This is not a kids’ story.

Read more: A Christmas story: the arrival of a sweet baby boy – or a political power to change the world

Biblical scholar Bill Loader asks us to imagine life in the first-century Roman Empire. He writes:

Ask Romans in Luke’s world, ‘Who is the Son of God?’ and they will point to the Emperor. Ask them: ‘Who is the bringer of peace?’ They will answer: ‘The Emperor’ and go on to explain that Rome’s armies cleared land routes of bandits and their ships, the sea routes of pirates, bringing the pax romana (Roman peace) to the world, making travel and trade safe.

So when the writer of Luke’s Gospel announces the birth of Jesus, describing him as the one who brings peace and calls him “son of God”, these are fighting words in an ancient context.

Luke, the author of the gospel that bears his name, doesn’t stop there. He records (Luke 1:33-34) Jesus’s mother, Mary, being told her son will inherit the “throne of his ancestor David” and “reign over the house of Jacob forever”. These are references to Jerusalem and Jewish self-rule over their traditional lands. It is a pointed promise given that Mary is living in occupied territory; land that Rome had conquered and colonised.

For Jesus to sit on David’s throne requires the emperor to vacate it. Jesus never threatened war, but subversion by force of ideas can be as dangerous as insurrection by violence. It’s perhaps no surprise that the imperially appointed client king, Herod, tried to kill Jesus while still an infant and the Romans killed him when a grown man.

Countless other examples could be offered of these early writers’ attempts to amplify the political environment of Jesus’s birth, life and death. They name the relevant emperors, use their epithets, evoke their iconography and claim the power and praise bestowed on the emperor more rightly belongs to Jesus.

That Jesus, a child from an ordinary Jewish family in non-urban, occupied Judea could be a threat to an emperor should be laughable hyperbole. Strangely, it is not presented as such in the gospels. Radical? Yes. Hyperbole? No.

This aspect of the Christmas story is often what sits most uncomfortably for Christians and non-Christians alike. I have frequently heard things like “keep politics out of it” (like when I write articles like this). I’ve heard colleagues criticised for mentioning things like the Black Lives Matter movement in a sermon because it’s “too political”. This is not universal, of course, but there is an unease when faith and politics combine.

In Australia we prefer faith to be private. We like our religion and our politics in two discrete categories, as if that is possible, as if one’s religion can be divorced from one’s values and life.

In a recent speech to parliament, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews referred to his faith as “personal and private”, acknowledging it is not something he usually speaks about as a politician. I can understand why, and this is not a criticism of Andrews. But it caught my attention because it is precisely what both the church and state have promoted for decades now – that religion is best in private. That is, if you just keep your religion to yourself we won’t have a problem.

Yet a robust notion of the secular includes religious and non-religious alike and is, I would argue, enhanced by open and public religious dialogue.

I suspect this emphasis on personal and private is why we are so affronted by obvious displays of faith like Muslim women wearing hijabs or Orthodox Jewish men wearing shtreimels or peyot. It’s too public, too visible a reminder of someone’s faith. It breaks the unspoken agreement that we keep our faith private and personal.

In the world from which the Bible emerged, the idea that religion and politics could be separated would have been considered ludicrous. Politics was religion and religion political. Both encompassed and informed the values that structured and organised society.

So when a group of Judeans proclaim their king has come and call him “Son of God”, they are proclaiming their allegiance to someone other than the emperor. That Christians would demand allegiance to Jesus alone was even worse in a religiously pluralistic society, leading others to call them “atheists” for their lack of general religiousity.

Are Christians still a political threat? It depends who you ask and where you live. Communist states and religion are notoriously poor bedfellows and the Christian church suffered greatly in Russia as it continues to in China.

In countries like North Korea, organised religions such as Christianity continue to be considered a threat to the state. What these states realise, perhaps more profoundly than the average Western churchgoer, is that Christianity is deeply political and, if lived out to its fullest potential, fundamentally threatening to those in power.

One way to mitigate such threat, of course, is to co-opt Christianity for nationalistic causes. Donald Trump has shown rare insight in doing just that.

Read more: Trump's photo op with church and Bible was offensive, but not new

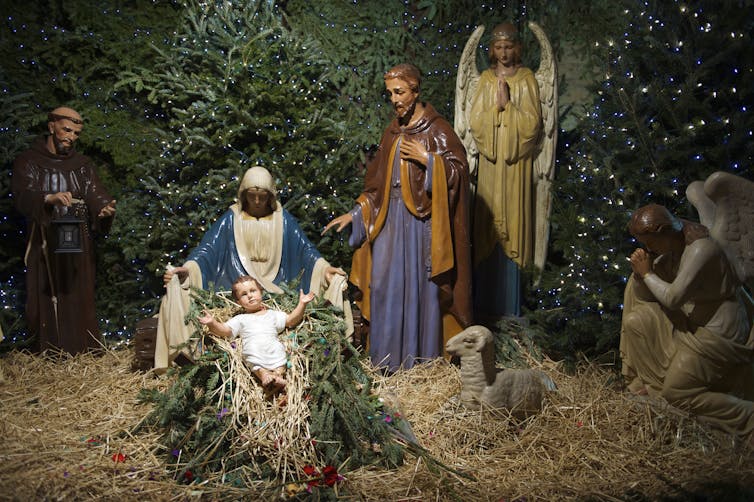

As a biblical scholar who spends a lot of time reading ancient texts, contemporary nativity scenes give me pause. They present a picture of domestic bliss, albeit a slightly strange one if you consider the stable scene (historically dubious and romanticised as it is).

Yet the Christmas story as told by Luke and Matthew in the Bible is not a safe, children’s story of domestic happiness. It is the beginning of a longer narrative of power challenged, justice demanded, love proclaimed, and certain worldly values overturned.

How can that not be political?

Robyn J. Whitaker, Senior Lecturer in New Testament, Pilgrim Theological College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.