Anastasiya Fiadotava, Jagiellonian University and Anna-Sophie Jürgens, Australian National University

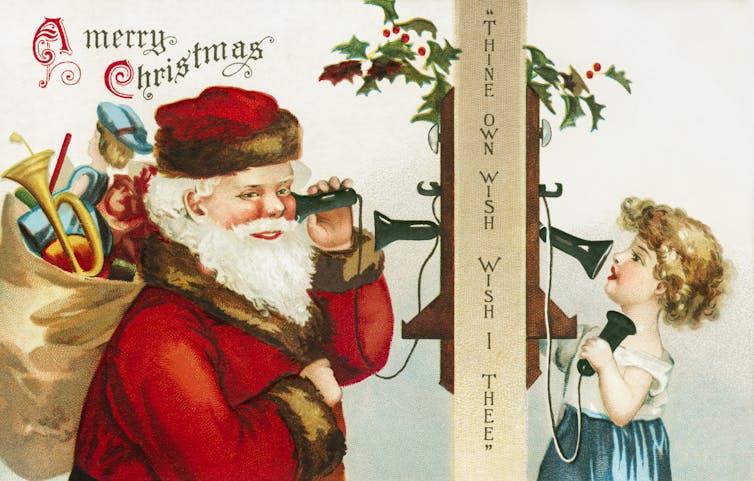

Here it is again: the merry, festive Christmas season with its glitter balls, tinsel and the typical “Ho Ho Ho!” Holding onto his red belly, Santa grins and laughs at us from everywhere. Like Halloween pumpkins and clowns, Santa is one of our most popular cultural symbols associated with laughter. In fact, Father Christmas, clowns and demonic veggie visages have more in common than you might think! And our pop culture depictions of Santa’s laughter tell us a lot about the pitfalls and promises of humour, and the not obvious links between humour and laughter.

Santa’s laughter is often benign. In the 1970 fantasy musical

.

The surreal 1959 Mexican fantasy film

is another great example. The film, which is hilariously outrageous from today’s perspective, shows Father Christmas as a good-natured, chubby bloke who lives in space and hardly says a word. Whether he peeks into children’s rooms on Earth through his cosmic telescope or gives them knockout drugs so that he can hand out his presents undisturbed, his sole comment and universal reaction to everything is a juicy “Ho ho ho!”This full-bellied “jolly old gentleman” might be a slacker 364 days a year, but he’s generally perceived as a harmless creature. His laughter seems to be inseparable from the festive Christmas atmosphere and is one of the most important audio stimuli in any holiday film. However, even the most good-natured cinematic Santa can’t help playing tricks on the devil and laughing heartily as they succeed. Thus he signals happiness, but also reveals that he and his laughter are not as harmless as they seem to be at the first sight.

The gloomier side of Santa

In stories where Santa is a laughing killer robot (e.g., in the Futurama episode

, humour and laughter here are not meant to foster social cohesion and community spirit. They rather signal the power one has over enemies, the malicious enjoyment of their failures or even an intention to kill them.In these cases, Santa’s laughter echoes the deadly laughter of Joker and other comic villains; it is a psychological weapon, yet another way to attack and defeat. Laughter is often accompanied with a grin, and barring the teeth can easily become threatening (“smiling” Halloween pumpkins do give us shivers!). In fact, these maliciously laughing monsters can surface before Christmas, adding a frightening layer to this holiday. Tim Burton’s Nightmare Before Christmas illustrates how evil creatures might try to hijack Christmas – including hijacking Santa’s laughter, which is clearly recognisable but sounds all the more scary when we hear it from a Pumpkin King Skellington. Such laughter has no connection to humour and comes rather closer to the risus sardonicus.

The different shades of Santa’s laughter mirror the various roles that laughter plays in human societies. It can represent and provide enjoyment but it can also have a darker side: when laughing at someone (as opposed to with them), we exclude them from the group, humiliate and denigrate them. Laughter can signal agreement, embarrassment, superiority, aggression – and paradoxically, these feelings can be mixed all together in the single utterance of laughter. Thus there is no clear line between merry and scary in our laughter.

Just like Santas and monsters, we enjoy the ambiguity of our laughter and know that sometimes it can tell much more than a thousand words. Laughter is often tightly connected to humour, but it is even stronger connected to human relationships. The time and context of our laughter – or, on the contrary, our unlaughter when we want to show explicitly that we are not amused – are also of crucial importance.

So keep an eye on your Santa this weekend and watch out if he is a benign “Ho Ho Ho!” dude or a side-splitting Joker Santa. And as you laugh at or with him, think of how much your laughter can mean to you and the people around you.![]()

Anastasiya Fiadotava, Assistant professor, Institute of English studies, Jagiellonian University and Anna-Sophie Jürgens, Assistant Professor in Popular Entertainment Studies, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.