If there’s one coronavirus mutation that keeps scientists awake at night, it’s E484K. The mutation was found in both the South African variant (B1351) and the Brazilian variant (P1), but not in the UK variant (B117). This so-called “escape mutation” raised fears that the approved COVID vaccines may not be as effective against these variants. The E484K mutation has now been found in the UK variant as well – albeit in just 11 cases.

The coronavirus mutates slowly, accumulating around two single-letter mutations per month in its genome. This rate of change is about half that of flu viruses. Early in the pandemic, few scientists were worried that the coronavirus would mutate into something more dangerous. But in November 2020, that swiftly changed when the first “variant of concern” was discovered. The newly discovered variant B117 was associated with the huge spike in cases in south-east England and London.

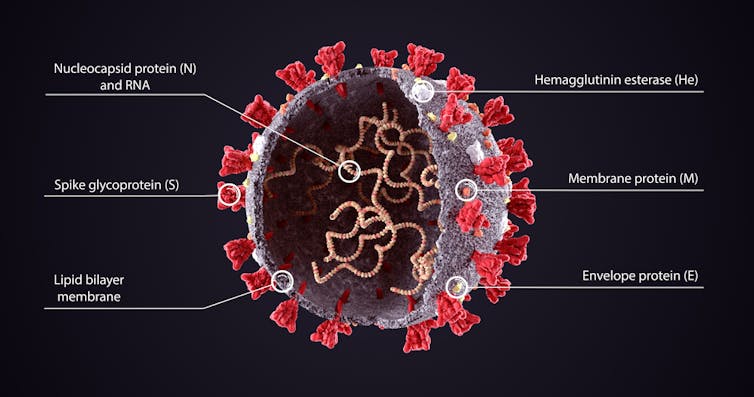

Receptor-binding domain

While all mutations found in emerging variants of coronavirus should be monitored, scientists are particularly interested in mutations occurring in the virus’s spike protein, specifically the receptor-binding domain (RBD) section of the spike protein. This section of the virus latches onto our cells and initiates infection. Mutations in the RBD can help the virus bind more tightly to our cells, making it more infectious.

The immunity we develop to the coronavirus, following vaccination or infection, is largely due to the development of antibodies that bind to the RBD. Mutations in this region can allow the virus to evade or partially evade these antibodies. This is the reason they are called “escape mutations”. E484K is one such mutation.

The mutation name comes from the position in the string of RNA (the virus’s genetic code) that it occurs (484). The letter E refers to the amino acid that was originally at this location (glutamic acid). And K refers to the amino acid that is now in that location (lysine).

Several studies have shown that mutation E484K stops antibodies that target this position from binding to it. However, after an infection or vaccination, we don’t produce antibodies targeting only one area of the virus. We produce a mixture of antibodies, each targeting different areas of the virus. How detrimental it is to lose the effect of antibodies targeting this one specific region will depend on how much our immune system relies on antibodies targeting this particular site.

Two studies, one in Seattle, the other in New York, investigated this. In the Seattle study, which is a preprint (meaning it is yet to be peer reviewed), scientists examined the ability of antibodies from eight people who had recovered from COVID to stop the mutated form of the virus infecting cells – in other words, to neutralise the virus.

In samples from three of the people, the ability of the antibodies to neutralise the virus was reduced by up to 90% when presented with the E484K mutated form. And it was reduced in samples from one person when presented with a different mutation at the same position. However, the neutralisation ability of samples from four of the people was unaffected by the mutation.

In the New York study, scientists examined the effect of a range of mutations on the ability of antibodies, collected from four people, to neutralise the virus. The researchers found that none of the antibodies were affected by the E484K mutation. Yet two of the samples saw a reduction in neutralisation ability when challenged with mutations occurring at different positions in the spike protein. This highlights the uniqueness of the antibody response produced by different people.

Both these laboratory studies used only a few samples collected from people who were naturally infected, as opposed to vaccinated, so the results may differ, as we know immunity gained through vaccination is generally more robust. Consequently, several research groups have recently released data, as preprints, examining the impact of this mutation on vaccine-induced protection.

Effect on vaccines

One of these studies, published by scientists in New York, looked at antibodies from 15 people vaccinated with either of the two approved mRNA-based vaccines (those produced by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna). The second, published by scientists in Texas in collaboration with Pfizer, looked at antibodies from 20 people vaccinated with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. A third, released by scientists in Cambridge, England,, looked at five people vaccinated with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Both the New York and Texas studies showed that while the effectiveness of the vaccine to protect against variants carrying the E484K mutation was slightly reduced for some people, it was still within an acceptable level. Decreases in antibody neutralisation ability are measured in “fold change”. As an example, the antibodies produced by an influenza vaccine would need to see a fold decrease of more than 4 before scientists would have to alter the vaccine.

The Texas study reported a fold decrease of 1.48 in antibodies, and the New York study reported fold decreases of between 1 and 3. However, the Cambridge study found that antibodies from three of the five people had a fold decrease greater than 4 when challenged with a virus carrying the E484K mutation.

A key difference between the Cambridge and US studies is that the US studies used the South African variant, whereas the Cambridge study introduced the E484K mutation into the UK variant (B117) and used this in their tests. This may indicate that the recent reports of the detection of this mutation in B117 should be of greater concern to UK health officials than the importation and subsequent circulation of the South African variant. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that the above studies are based on very small sample numbers and any conclusions should be drawn with caution.

Nevertheless, it highlights the importance of examining the combined effect of multiple mutations as opposed to studying only individual ones, as it is unlikely that any single mutation would lead to complete escape from natural or vaccine-derived immunity.

Claire Crossan, Research Fellow, Virology, Glasgow Caledonian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.