Jessica Borge, School of Advanced Study

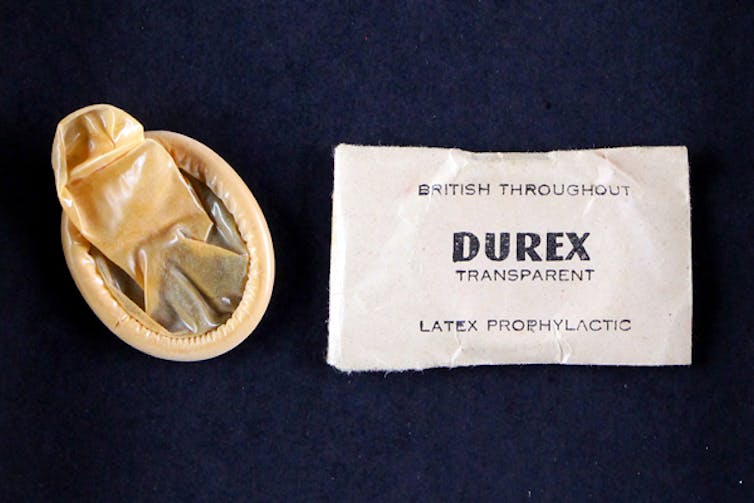

Around 975 Durex condoms are sold every minute. The global condom market is predicted to grow to over US$11 billion (£8 billion) by 2023, and Durex is in the privileged position of being the world’s most popular brand. Yet until recently, the young man who invented Durex’s mass-produced condom had been forgotten – even by the manufacturer itself.

The origins of Durex go back to the London Rubber Company, which began trading in 1915 and specialised in importing modern, disposable condoms for re-sale in Great Britain. In 1932 the firm underwent a game-changing switch from wholesaling to fabrication, when it started manufacturing in-house under the Durex brand. By the mid-1940s, London Rubber had the biggest production capacity in Britain, and by the mid-1960s, the world.

Listen to an audio version of this story on The Conversation’s In Depth Out Loud podcast, narrated in partnership with Noa.

As a social historian with an interest in businesses, I had been intrigued by London Rubber ever since a friend pointed out the then-derelict factory in Chingford in the late 1990s, after production was moved to Asia. I was fascinated by the idea that thousands of ordinary Londoners made their living from condoms, and set about researching the topic for my PhD. Turning this work into a book gave me the opportunity to deepen my research.

The one question I really wanted to answer was who actually invented Durex condoms. They have long been attributed to a man called Lionel Alfred Jackson, a third-generation Russian-Jewish immigrant who founded London Rubber in 1915. It was Jackson who, in 1929, patented the Durex trademark (standing for “Durability, Reliability, and Excellence”). But surely there was more to this story?

My style of research involves the painstaking examination of documents. But as no company archive for London Rubber is available to researchers, my investigation has involved forensic detective work, with discoveries often coming about through hunches.

The memorable name “Lucian Landau” had popped up in correspondence between London Rubber and the Family Planning Association (held at Wellcome Collection) and on patents. But Landau wasn’t mentioned in the few official documents archived at Vestry House Museum, or in the company magazine London Image, which had been supplied to me by ex-London Rubber employee Angela Wagstaff. This piqued my interest: Landau must have been somebody important if he was on the patents.

I checked the British Library on the off-chance it held some reference to Landau and was thrilled to find a rare copy of his self-published autobiography. Incredibly, Landau had written the story of his involvement with London Rubber. I was able to triangulate his account with the rest of my evidence, and the pieces fell into place.

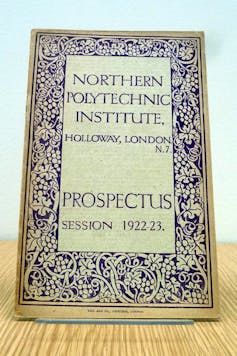

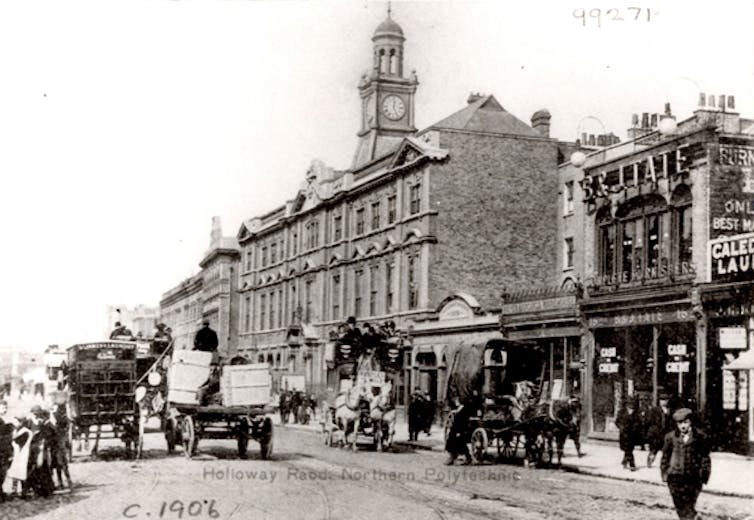

What I discovered was that while Jackson came up with the business model for supplying condoms, the technology behind Durex was invented by Landau, a Polish teenager living in Highbury and studying rubber technology at the former Northern Polytechnic (now London Metropolitan University).

His story is fascinating: Landau had left London Rubber under a cloud in 1953 and was erased from the official company history. He then built a new life for himself as a medium and psychic investigator. Until now, Landau’s centrality to the modern condom has gone unrecognised. But if Landau was so important to London Rubber, how did he come to be erased from the history of Durex condoms?

Landau in London

Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1912, Landau was sent to London to study rubber technology by his family, who were small-time industrialists dealing in rubber, perfume, cosmetics and soap.

It was 1929 and he was only 17. The expectation was that, once trained, he would return to Poland and take over his father’s business. But Landau soon realised he adored London and did not want to leave. “I felt more at home here than I ever felt in Warsaw,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I felt I could never leave this place.”

Attending rubber technology classes in Holloway and living with other boarders (and a singing parrot) in Highbury Place, his great pleasure was to explore the local area on foot. Upper Street and Chapel Market were favourites, and Landau quickly learned the streets of Islington, Hackney and Camden, the City and West End. “I was mainly interested in shop windows,” he said, “and particularly in various rubber articles.”

Having tasted independence, Landau was ready to go it alone in London but was ineligible to seek employment under his student visa. He could, however, start a business. His fascination with shop windows in this nation of shopkeepers would prove key.

Unconvinced of the quality of rubber toilet sponges available, Landau developed a new sponge process in the polytechnic’s lab, set up a manufacturing firm and offered employment. The Home Office granted him leave to remain, so long as business continued.

But Landau was dissatisfied with toilet sponges. It was while experimenting with a Pirelli latex sample and some glass tubing, Landau writes, that he hit upon the idea of making latex condoms. “I knew that these products were all imported from Germany and America and there was no British manufacturer,” he wrote. “The plant required would be simple to construct and I could probably make it myself.”

Condoms have been around since ancient times. Early versions were often made from

discovery of vulcanisation – the heat treatment of rubber – in the 1840s, heavy-weight, re-usable rubber sheaths were made. But these were far from ideal, having a bulky and uncomfortable seam along the lower edge.Improvements towards the end of the 19th century led to condoms being made by dipping condom-shaped formers into a sort of rubber cement. This got rid of the seam but the process involved inflammable solvents that sometimes led factories to catch fire. But by the 1920s, condoms were being made using a safe latex dipping process developed in Germany and America. Latex was relatively new in Britain, giving Landau a first-mover advantage.

Travelling condom salesman

Hoping to generate interest in his new product, Landau revisited the shops from his walks. As luck would have it, a “Mr French” who ran a retail pharmacy at the corner of Mare Street and Well Street, Hackney, suggested that Landau seek out the legendary Lionel Jackson.

A travelling condom salesman, Jackson had put in the leg work visiting retailers – chemists’ shops, herbalists and “hygienic stores” – up and down the country, selling bought-in condoms wholesale for his company, London Rubber. Well known and respected, Jackson offered stockists a personal service and competitive margins.

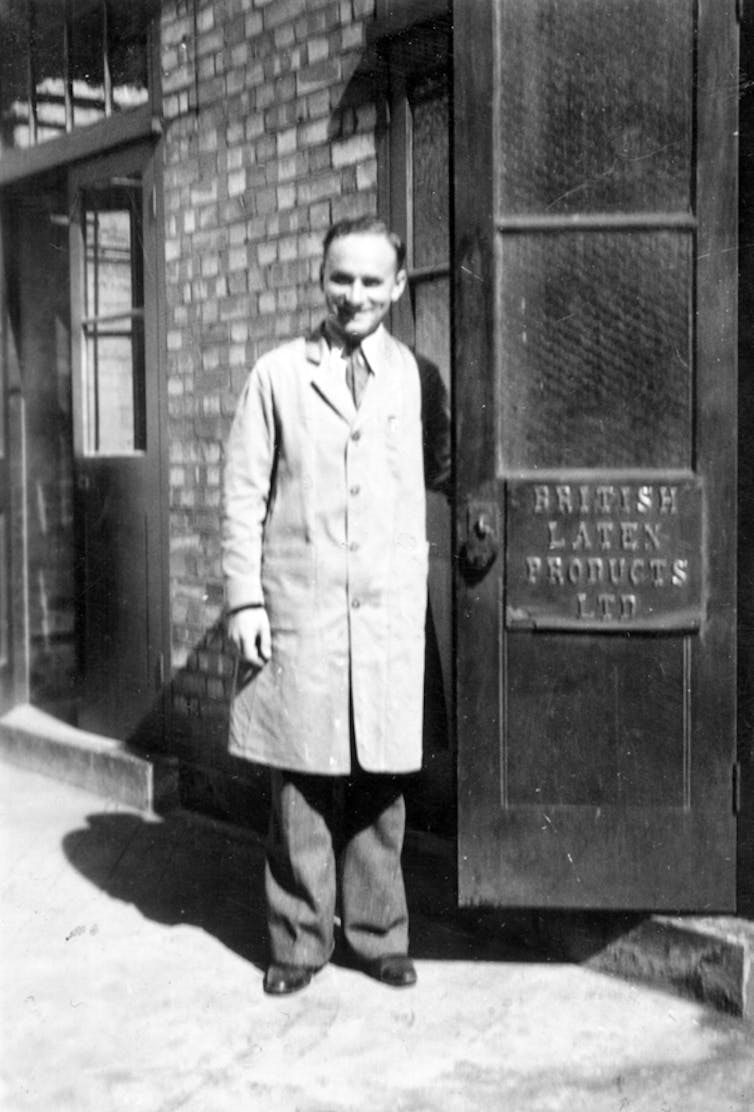

Landau’s expertise in the production of rubber consumables presented Jackson with an exciting prospect: the chance to compete directly with manufacturers. So Jackson loaned Landau £600 to set up British Latex Products, to supply condoms to London Rubber under the Durex brand. Jackson took a 60% controlling share, retaining Landau at £5 per week.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Manual condom production began in 1932 underneath the “Rock-A-Bye” baby shoe works on a small industrial estate on Shore Road. Landau was barely 20 years old. Jackson gave Landau freedom to design and organise his plant without interference, and the two got along, Jackson being one of the few people at London Rubber whom Landau ever genuinely liked.

But in 1934, aged just 40, Jackson died from cancer of the spine. According to Landau’s autobiography, this had spread throughout his body and caused him enormous pain. His death was unexpected and there was no will, so his brother, Elkan, and sisters, Mrs Collins and Mrs Power, inherited the company. Operations were run by the young Angus Reid, who had been the first hire outside of the family eight years before Landau entered the scene.

Landau was not pleased with the new setup. He felt the remaining Jacksons to be “of limited intelligence” and found Elkan in particular a thorn in his side, although others at the firm spoke warmly of the man, who laughed a lot and brought everybody cakes. Years of animus followed and Landau experienced little contact with executives, preferring the methodical calm of his workshop.

Nonetheless, Landau was vital to London Rubber and remained in charge of production and R&D, overseeing the firm’s relocation to a purpose-built factory in Chingford in the late 1930s. It was here that Landau really began developing his technical ingenuity in condom production, especially during the second world war. Tested by wartime conditions, Landau had to find ways to produce a consistent product with varying qualities of latex.

From 1942, and under the wartime rationalisation scheme, latex was diverted to Chingford (and, crucially, away from competitors) so that London Rubber could supply the British forces with condoms. For a period, production was moved to a safer site underneath the Chingford viaduct, to protect workers (and condoms) from enemy bombing.

At this stage, condom production was still a largely manual process, although some of the actual dipping was electronically assisted. Important parts of the process, such as stripping and testing the finished product, were done entirely by hand. The Herculean efforts involved in wartime production saw Landau maximise yield under pressured conditions. This ensured that, coming out of the war, London Rubber was Britain’s biggest condom manufacturer.

The machines that made Durex

After the war, Landau was made a director of London Rubber. But although he oversaw some important business decisions (such as taking the company public in 1950) his strength and legacy lay in technical achievements, which I have been able to corroborate by comparing his autobiography with my databank of documentary sources.

In particular, he was responsible for designing the sophisticated “automated protective” lines installed at the Chingford factory, “protective” being the preferred London Rubber word for condom. Together with the Durex brand, forever synonymised with condoms following the war, Landau’s automated machines constituted the strongest barrier to competition wielded by London Rubber.

Though developed by Landau in the 1940s, the first two automated machines were not installed until 1950 and 1952, after the wartime rationing of steel had ended. Each was about 200 yards long and had two “double decker” production lines, wherein hollow glass formers were dipped into two latex baths, on a large conveyor belt. These “double-dipped” condoms were then heat-treated, rinsed and rolled up by spinning brushes before being passed through a chalk solution to prevent sticking. They were then collected into a chute for air testing.

Incredibly, colour footage of this entire process survives, having been included in an award-winning educational film, According to Plan, produced by the company in 1964, which I have written about elsewhere.

Thanks to these marvellous machines, production increased from 2 million condoms a year in the early 1930s, when the latex dipping was done manually, to the same volume each week in the early 1950s. By 1954, weekly production ran at 2.5 million, and there was there was a 29-fold increase in output overall as lines were added between 1951 and 1960.

Landau wasn’t the only inventor to create dipping chains. Fred Killian in Akron, Ohio, developed a similar technology in the 1930s. But whereas American condom manufacturers (such as Youngs) had to lease the Killian model, London Rubber’s machines were unique in Britain and protected by patent, meaning London Rubber could produce at economies of scale unmatched by other local producers. The product was also top quality, as I found out when I repeated a 1960s consumer test by filling an original 1967 Durex Gossamer with five pints of water as part of a

I delivered.But success also marked the end of the line for Landau, who had been harbouring ill feeling ever since Lionel Jackson’s death. This had been exacerbated by alleged dodgy dealings during the war when, Landau claims in his autobiography, Elkan Jackson and Angus Reid sold condoms on the black market.

After the war, a taxman shadowed Landau for a whole month while the company was under investigation for tax evasion related to the alleged black-marketing. In the end, Landau was cleared but Jackson and Reid (Landau wrote) were fined. Landau insisted upon his appointment to the board and 20% of London Rubber shares as compensation for being put in such a difficult position.

But these incidents never left him. Bad feeling was compounded by a series of unfortunate events in the 1950s, which led to his leaving the company for good.

Landau’s last days

London Rubber was a family firm with a positive ethos, routinely marking the achievements of its staff with a characteristic sense of occasion that made it an eventful and pleasant place to work. Life events (such as marriages and babies), as well as loyalty, were marked by the ceremonial giving of clocks, watches, layettes and other gifts.

Landau, by all accounts a deep-feeling but standoffish man, tended to keep himself to himself. Nonetheless, by the time his 21st work anniversary came up in 1953, he had a reasonable expectation that his tremendous accomplishments would be recognised. But the anniversary slipped by unmentioned and Landau did not receive the customary gold watch. This is seemingly corroborated by the absence of his name on the Long Service wall of fame (which was photographed for the company magazine, London Image, in 1969) and Landau was completely elided from official company histories – until I rediscovered him.

Historians of contraception and condoms (and, indeed, the companies that subsequently inherited the Durex brand) cannot be blamed for overlooking Landau. I did the same before I looked deeper, particularly as the Lionel Jackson founding story was so convenient.

But at the time, the neglect of Landau’s milestone seemed deliberate to him, and in the absence of internal company records, his is the only account of the incident we have. Personal misfortune befell Landau in the summer of 1953 during a love affair with switchboard operator Alice Maud (during his second divorce), which made them the subject of office gossip. Tragically, Maud took her own life, leaving Landau reeling. He kept the two aspirin bottles she had emptied for the rest of his life.

Back at London Rubber, tongues were wagging and Landau was miserable. “I asked myself why I should continue to work with people whom I did not like, and who did not really appreciate all I was doing,” he wrote. Enough was enough, and he resigned. Although some colleagues were markedly upset (his secretary also resigned in sympathy) there was little love lost. Landau picked up his things in September 1953 and never set eyes upon London Rubber again.

At 42, Landau was still young and, with abundant shares and savings from London Rubber to support him, was free to pursue other interests alongside occasional consultancy work. He possessed a strong interest in spiritual matters, including mediumship (making contact with the dead), which was not unusual in the 20th century and was referenced fairly regularly in popular culture.

Landau’s interest became more important when, as Landau wrote in his autobiography, he began to hear Maud speaking to him after her death, advising on day-to-day matters such as catching the correct tube train, which Landau reported finding useful. Apparently she had also passed a message from beyond the grave to the clairvoyant Florence Thompson, who Landau happened to see shortly after resigning. The message was to the point: Maud was sorry for what she had done but could not undo it.

Economically independent, making new friends and forever moved by his relationship with Maud, Landau spent the next 50 years developing his abilities as a medium through the London Spiritualist Alliance (now College of Psychic Studies) and the Society for Psychical Research, in combination with investigating psychic phenomena.

Landau’s early adulthood had been monopolised by London Rubber, but his awareness of strange and seemingly inexplicable happenings had been with him since at least the 1930s, when he first started making condoms. Amazingly, there is video footage of a very elderly Landau recalling his “psychic experiences”, which I was directed to by the author Christopher Josiffe. It was only when I actually watched the video that I realised Landau had been captured describing a supposed incident of psychic healing that took place in the first factory in the 1930s, and described in his autobiography.

A girl’s hand had been crushed by a condom dipping rack but Landau, he wrote, healed her bloody, mangled fingers by holding them. The girl was apparently so grateful that she named her son after him. The video of him recounting this incident was filmed by Landau’s friend and colleague from the SPR, the late Mary Rose Barrington, who was a loyal supporter and wanted Landau’s achievements recognised. The society has kindly granted permission for me to show this excerpt for the first time.

Landau had many mysterious experiences throughout his life, which are recounted in various volumes written by and for the wider community of people interested in psychic phenomena. He also published many papers on dowsing, but never lost his aptitude for everyday technical solutions, doing odd jobs around the College of Psychic Studies, such as mending televisions and plumbing.

But it was through his participation in London psychic and spiritualist communities in later life that Landau ultimately found happiness, meeting his third wife Eileen in 1955, and moving to the Isle of Man in 1967. Lucian Landau, psychic investigator, medium, dowser and original Durex technologist died in 2001, satisfied that his life’s work was complete.

Landau’s automated machines were in use up until the closure of the Chingford production plant in the summer of 1994. Today, delightfully, Landau’s name has been restored to the official history of Durex following early publicity for my book.

I was hoping this would happen. It is easy to be cynical, but sometimes we only need look a little deeper to find the human story behind that which we take for granted.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Robots were dreamt up 100 years ago – why haven’t our fears about them changed since?

‘We will not forget our colleagues who have died’: two doctors on the frontline of the second wave

This is what happened the morning the first atomic bomb created a new world

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Jessica Borge, Digital Collections (Scholarship) Manager at King’s College London Archives and Research Collections; Visiting Fellow in Digital Humanities, School of Advanced Study

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.