Mark Frydenberg, Monash University

When compared with mammograms and pap tests, the PSA test isn’t as effective in detecting early prostate cancer. But for now, at least, it’s the best test we’ve got. And if it means lives will be saved from this deadly disease, it’s certainly worth the effort of getting tested.

The prostate explained

The prostate is a walnut-shaped reproductive organ that sits just below the bladder and is responsible for producing ejaculate fluid.

Prostate cancer, like other cancers, occurs when cell growth becomes uncontrolled and excessive. The abnormal cells continue multiplying until they invade the blood vessels and spread to other parts of the body. Eventually these cell mutations reach the vital organs and the body shuts down.

The cause of prostate cancer is unknown, but genetics and age are key risk factors. The older you get, the greater your risk of prostate cancer.

In fact, by the age of 80, more than 75% of men will have been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Aside from skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed male cancer. It’s the second leading cause of male cancer death, after lung cancer.

PSA tests

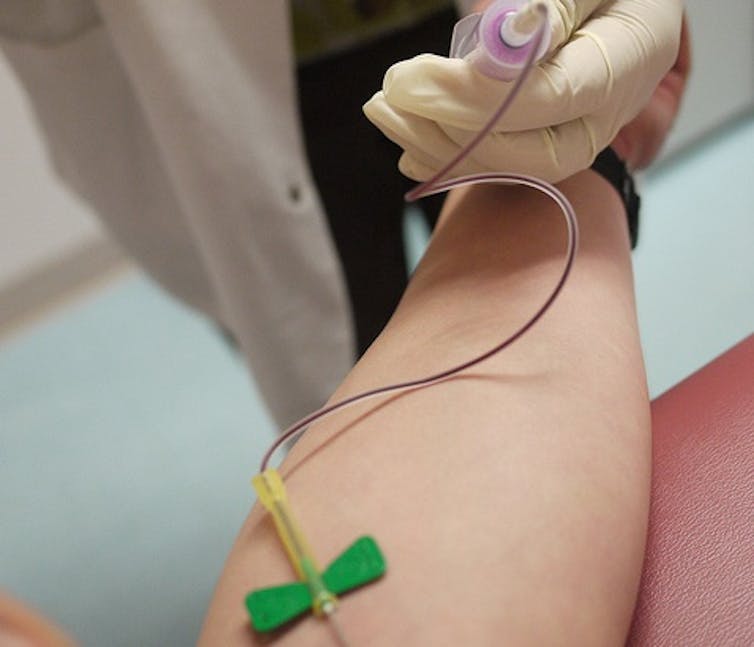

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is a protein made by the prostate. Small amounts of PSA make their way into the blood stream and the higher these levels of PSA, the higher the risk of developing prostate cancer.

So measuring blood levels of this protein has been the cornerstone of any early detection strategy over the last two decades.

Interest in the use of PSA as a screening tool began 1993 when urologists in Tyrol, Austria, introduced free PSA-based testing to its men over 50 years of age. The trial was a success, with the prostate cancer death rate reducing by 25% compared with the rest of Austria.

Since then, randomised controlled studies comparing death rates of men who have had PSA tests with those who haven’t have delivered conflicting conclusions so it’s worth taking a more detailed look.

The American PLCO (Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovary) trial found there was no difference in death rates between men had PSA tests and not.

But the problem with this trial was the follow up was too short, with men only being watched on average for seven years. And in the group of men who were not supposed to have a PSA test, about 50% actually did, which largely invalidates the results of this study.

The second recent study, the European Randomised Screening Trial in Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), did show a survival benefit in the long term (greater than nine years follow up), with 31% of men less likely to die from prostate cancer if they were tested compared to those that were not.

Another recent study from the Swedish arm of the ERSPC followed men for 14 years after their PSA test and found a 44% reduction in cancer death rates.

So it is now clear that PSA-based testing will save lives, but at what cost?

Over treatment

Some men will be diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer (who perhaps don’t need this intervention) in order to save other men from dying of prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer treatments such as surgery and radiotherapy can cause erectile dysfunction, and bowel and urinary problems, in a small percentage of patients which significantly reduces their quality of life.

But this problem of over-treatment is overcome by “active surveillance”: monitoring but not immediately treating every prostate cancer that is diagnosed.

At least 50% of new prostate cancer diagnoses in Australia are small, relatively non-aggressive prostate cancers. In these patients, the urologist will just monitor the disease. If it appears to be getting worse, they’ll be treated, otherwise they’re left alone.

Most studies show that after 10 years of active surveillance, the prostate cancer death rate is as low as 1%, with 30% to 50% of patients requiring treatment during that period.

As such urologists carefully individualise treatment decisions and only recommend treatment to those men who are at risk of their prostate cancer progressing.

Who should we test?

This is a major problem because of the mixed messages that GPs are receiving from peak bodies – in this country and elsewhere.

A recent US study showed only 24% of men aged 50 to 54 years had undergone a PSA test, even though this is the population group that would most benefit from prostate cancer testing.

Compare this with the 46% of men aged 70 to 74 years, and 24% of men greater than 85 years of age who were tested. These men are far less likely to benefit from prostate cancer testing because at that age, the threat of death from prostate cancer is surpassed by the risk of heart disease, stroke and other causes.

In this sense, older men are more likely to die with prostate cancer, than die of prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer is quite rare in men under 50 years of age, so annual PSA testing is also a poor use of resources. We need to find a balance.

Studies show a single PSA test at age 40 years of age predicts the likelihood of prostate cancer developing over the next 10 to 15 years.

For example, the ERSPC study showed that a single PSA level of greater than 2 nanograms per millilitre (ng/ml) increased the risk of prostate cancer death (not just diagnosis) by 7.6 times compared with a PSA of less than 1 ng/ml.

So there is a lot of value in a single test at age 40. If the levels and risks are low, the doctor can recommend delaying the next PSA test for five to 10 years, while those men with higher levels are watched more closely.

This is a way of testing “smarter” and using resources responsibly. However to do this, all health agencies must provide a clear and consistent message to consumers and guidelines to GPs, which is something that’s been lacking in this debate for the last 20 years.

The efficacy of Government-funded population-based screening needs to demonstrate not only a survival benefit but also cost effectiveness, and the latter has not been fully evaluated.

Until it is, it will be difficult to fully recommend population based screening.

But individual early detection cannot be refused to a well-informed man who requests a PSA test. It may well save his life.![]()

Mark Frydenberg, Head of Urology at Monash Medical Centre and Associate Professor of Surgery, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.