Laura Harper, Monash University; Alysia Bennett, Monash University, and Ross Brewin, Monash University

The question of what to do with abandoned mine sites confronts both regional communities and mining companies in the wake of Australia’s recent mining boom. The companies are increasingly required to consider site remediation and reuse. Ex-mining sites do present challenges, but also hold opportunities for regional areas.

Read more: No to rehab? The mining downturn risks making mine clean-ups even more of an afterthought

Old mine sites can provide a foundation for unique urban patterns, functions and transformations, as they have done in the past. It is useful to look at historical gold-mining regions, such as the Victorian goldfields, to understand how these sites have shaped the organisation and character of their towns.

Research by The University of Queensland’s Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation suggests Australia has more than 50,000 abandoned mine sites. Some are in isolated places. But many others are close to or embedded within regional settlements that developed specifically to support and enable mining activity.

Abandoned mines present unique challenges for remediation:

- the sites are large (sometimes enormous)

- their landscapes are environmentally and structurally degraded

- sites are often contaminated by substances used in processing – like arsenic in the case of historical goldmines.

Read more: Soil arsenic from mining waste poses long-term health threats

These characteristics exclude mining sites from reuse for activities such as residential development. The sites are often considered fundamentally problematic. At times former mining sites have been reused opportunistically, accommodating functions and uses that could co-exist with the compromised physical landscape.

How have old mines shaped our towns?

The industrial patterns established during the Victorian gold-mining boom are traceable through observing the street layout and the location of civic buildings, public functions and open spaces of former gold-mining towns.

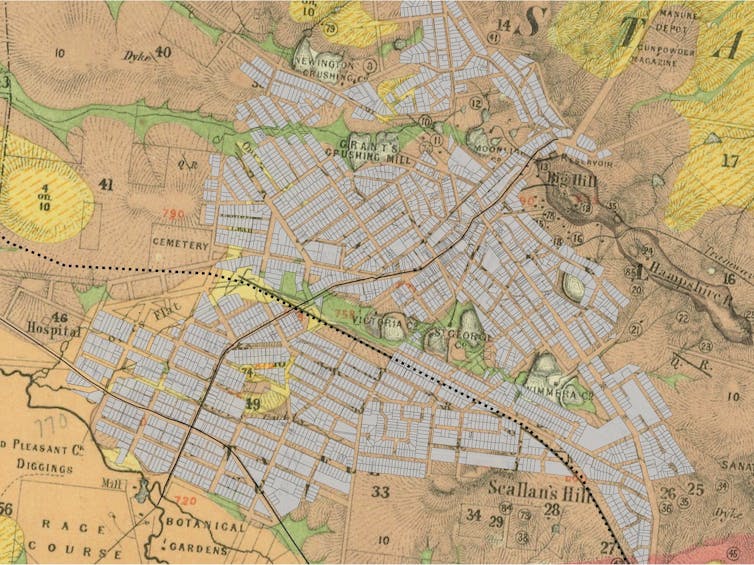

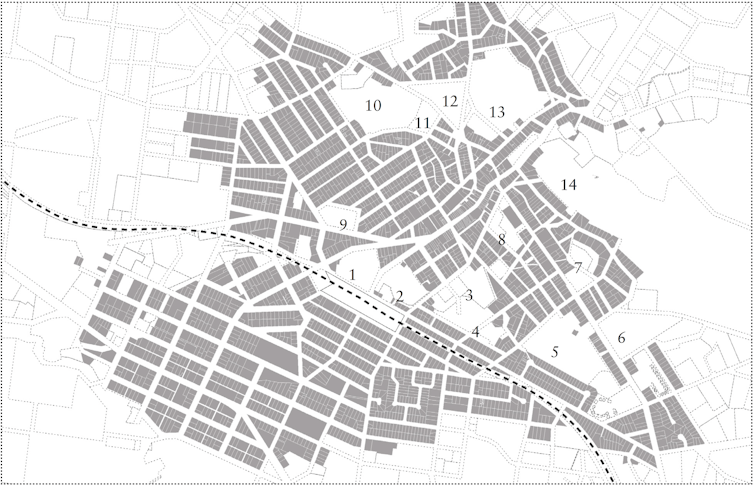

For example, in the gold-mining town of Stawell, a pattern of informal and winding tracks was established between mining functions. These tracks later provided the basis for the town’s street organisation and land division, including the meandering Main Street, which forms the central spine of the town.

Cato Lake, behind Main Street, was transformed from the tailings dam of the Victoria Crushing Mill. St Georges Crushing Mill and its associated dams became the Stawell Wetlands.

Other mining sites were transformed into the car park for Stawell Regional Health, the track for Stawell Harness Racing Club and the ovals for the local secondary college. A survey of public open spaces in Stawell shows that over time former mining sites accommodated most of the town’s public functions.

Many other Victorian goldfields towns developed in similar ways to Stawell. These towns have lakes or other water bodies in and around their central urban areas that were born out of mines.

Calembeen Park and St Georges Lake in Creswick and Lake Daylesford in Daylesford were all formed through the planned collapsing of multiple underground mines to create urban outdoor swimming spots.

In Bendigo, the ornamental Lake Weeroona was formed on the site of the alluvial diggings. Other sites in these towns became parks, ovals, rubbish tips and public functions that could be accommodated on the degraded land.

Abandoned mine sites outside towns have also been used for unique purposes. Deemed unsuitable for use by the farming and forestry industries, these sites have developed into havens for flora and fauna, including endangered species. A 2015 article in Wildlife Australia magazine details instances of the Eastern Bentwing-bat and the Australian Ghost Bat adopting abandoned gold mines as replacement habitat for breeding and raising their young.

The neglect of other gold-mining sites has preserved historical remnants by default. The Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park in Victoria is one example. Here, water races, puddling machines and crushing batteries are hidden amid dense bushland.

The town of Gwalia in Western Australia, abandoned after its mine closed, has been transformed into a town-sized open-air museum.

And what uses are possible in future?

Historical gold-mining sites in or near towns continue to be adapted for unusual uses. The Stawell Goldmine on Big Hill in Stawell is being converted to accommodate the Stawell Underground Physics Laboratory (SUPL), a research laboratory one kilometre below the surface. Cosmic waves are unable to infiltrate the abandoned mining tunnels, so the conditions are ideal for exploring the theorised existence of dark matter.

Read more: Digging for cosmic gold: the hunt for dark matter at the bottom of a gold mine

In Bendigo it is proposed to use the extensive historical mine shafts under the town to generate and store pumped hydroelectricity. This scheme, recently explored as a feasibility study by Bendigo Sustainability Group, would use solar panels to create power to pump underground water up through the mining shafts to be stored at the surface. When power is required the water would be released through turbines to generate electricity.

The lack of demand for remediating sites for market-led uses (such as urban development, farming or forestry) broadens their potential for uses that might otherwise seem marginal or improbable, such as new forms of public space.

Read more: From mine to wine: creative uses for old holes in the ground

The scale and remoteness of many post-industrial mining sites in Australia – such as Western Australia’s Super Pit gold mine, which is 3.5 kilometres long and 600 metres deep – might mean that approaches to reuse different from those taken with historical goldmines are required. We don’t have to wait until a mine’s closure to think about how it might be used in the future.

The Conversation is co-publishing articles with Future West (Australian Urbanism), produced by the University of Western Australia’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts. These articles look towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point, with the latest series focusing on the regions. You can read other articles here.

Laura Harper, Lecturer in Architecture, Monash University; Alysia Bennett, Lecturer and Researcher, Department of Architecture, Monash University, and Ross Brewin, Senior Lecturer, Department of Architecture, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.