Nicolas Florquin, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID); Alaa Tartir, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID), and Anthony Obayi Onyishi, University of Nigeria

In January 2022, in a bid to stem a tide of violent attacks and kidnappings in north-western Nigeria, the government labelled the armed groups involved in the violence “terrorists”.

The relationship between these groups and the internationally designated terrorist groups Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa Province in north-eastern Nigeria was unclear.

But the decision illustrated growing concern that violent extremism might spread to the country’s north-west. It also raised questions about the types of measures that were needed to prevent escalation of violence.

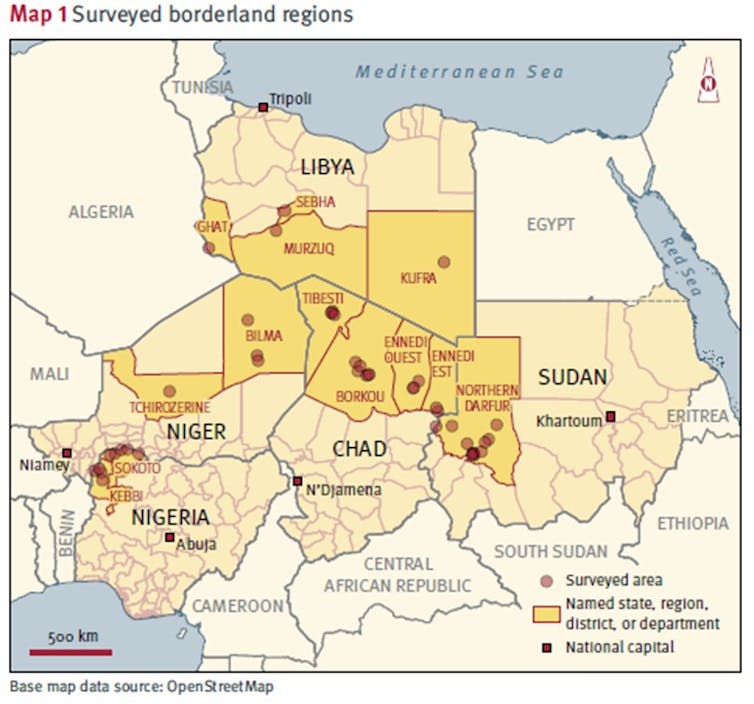

The Small Arms Survey and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) recently launched a new report assessing the threat of violent extremism in this border region, as well as in four other border areas in northern Chad, southern Libya, north-eastern Niger, and western Sudan.

We contributed to the report, which builds on the UNDP’s 2017 Journey to Extremism in Africa study. That study found that individuals raised in marginalised borderlands can be especially vulnerable to recruitment by violent extremist groups. Hence the focus on border regions and prevention in the new report.

The Small Arms Survey is an internationally funded programme. It has an extensive track record in research on weapons and armed actors in Nigeria, and the broader West Africa and Sahel region.

Marginalised border communities are also seen as vulnerable to the proliferation of illicit small arms.

By relying on general population surveys, the report shows how local societies are, or could be affected by violent extremism. It aims to inform policy making and programming for prevention.

The study

The study surveyed people’s perceptions of drivers (or root factors), actors and values associated with violent extremism. It is based on 6,852 interviews between December 2020 and July 2021, including 1,643 in north-western Nigeria.

The surveyed regions were not considered to be hotspots of violent extremism. We selected them due to concerns that terrorist organisations operating nearby might eventually expand their activities to these areas.

The study included north-western Nigeria because of the conflict there between Fulani herders and Hausa farmers over pastoral and agricultural resources, as well as competition over emerging mining opportunities.

It was also important to take into account the transnational dimension of conflict drivers. Government policies on border management, such as permissive immigration policies, might be relevant.

A range of armed groups have perpetrated violence in north-western Nigeria. Among them are vigilantes, criminal gangs, herder-allied groups and jihadists. Local “bandits” also appear to be mingling with violent extremist groups.

Armed groups in the region have used locally manufactured firearms and factory-produced small arms. The weapons reportedly come from other countries in the region and from within Nigeria.

Drivers of violent extremism

The seven drivers of conflict we focused on were:

hardship and deprivation

lack of adequate security and justice

limited access to basic services

the growing importance of ethnic or religious identities

chronic instability and insecurity

blocked political participation and the influence of non-state armed groups

the illicit proliferation of small arms and light weapons.

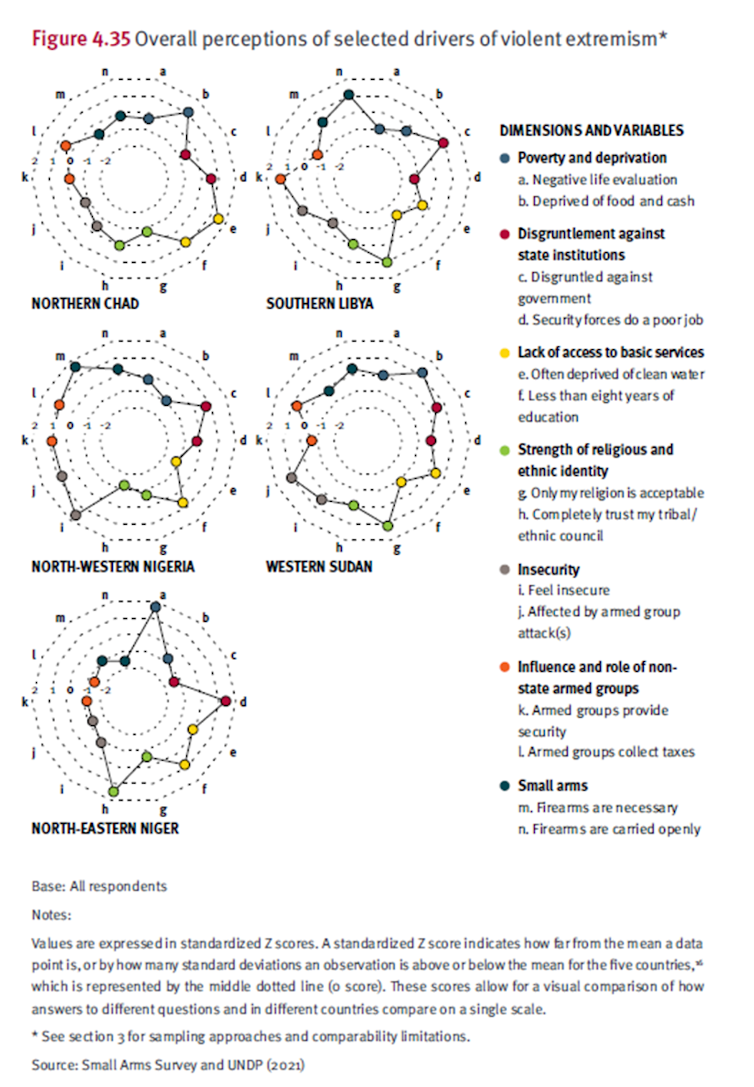

Figure 4.35 shows that exposure to the various drivers depends on the context of each region.

Reducing vulnerability to violent extremism will require putting each region’s most relevant needs and grievances first.

The situation in north-western Nigeria

Overall, north-western Nigeria appeared less exposed to strong religious and ethnic identities, and to poverty and deprivation than the other four case studies.

On the other hand, the Nigerian respondents reported higher than average levels of disgruntlement with the government, and north-western Nigeria also stood out as vulnerable to discrimination and marginalisation along identity lines. Interestingly, dissatisfaction with security forces was not as strong as with the government. But perceived insecurity was the highest in north-western Nigeria.

Respondents felt strongly that women and youth were under-represented in leadership, community and political roles. The region also reported the study’s highest levels of victimisation to gender-based violence — by a significant margin.

The region’s respondents reported the highest levels of proliferation of small arms. They reported flows of small arms with other regions of the country and other countries in the region. They were particular about Niger, Chad, Libya and Mali.

A significant 19% of respondents in all regions reported being aware of recruitment by local or foreign armed groups in their communities. The rate in north-western Nigeria was the highest at 35%. This shows the border region’s particular exposure to the activities of non-state armed groups.

Interviewees in all regions said armed groups recruited both men and boys, and women and girls.

Armed groups were not only seen as a threat. In some instances their role was perceived as positive. For example, some respondents noted that armed groups offered protection, owned businesses, and provided cash income.

Respondents also felt more secure where security providers were a mix of national and local actors, including non-state actors.

What must be done

Policies and responses need to take into account these complex dynamics. Interventions that focus purely on security could have a negative impact on local economies and informal trade flows.

The report’s findings can be challenging to interpret. This is because we do not have a baseline to compare them to. But the study shows that extreme views are held by about 3% of the population in the five regions surveyed.

If measures don’t address the specific needs, vulnerabilities and grudges of border communities, radical views could well gain more ground and translate into increased violence.

Implementing timely and context-specific preventive measures will be critical for reducing the risk of violent extremism in these border regions.

Such measures should form part of broader regional development and stabilisation efforts, to prevent extremist groups from taking advantage of a vacuum or lack of state services.

They may also involve community-led engagement and dialogue to address social cohesion challenges. Interventions in areas that are highly dependent on cross-border trade will be essential, yet particularly challenging.

The affected population and their perceptions should be at the centre of interventions.

Acknowledgement: The report discussed in this article is a joint publication of the Small Arms Survey and the UNDP’s Regional Prevention of Violent Extremism Project for Africa - which is a joint initiative of the UNDP Regional Bureaus of Africa and the Arab States. It benefited from the support of the governments of the Netherlands and Sweden. In addition to the authors, Darine Atwa, SANA project assistant, and Gergely Hideg, survey specialist, both at the Small Arms Survey, contributed to the writing of this article.![]()

Nicolas Florquin, Head of Data & Analytics and Senior Researcher for the Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID); Alaa Tartir, Senior Researcher and Coordinator of the Security Assessment in North Africa project at the Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID), and Anthony Obayi Onyishi, Professor of Political Science & International Relations, University of Nigeria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.