Sallek Yaks Musa, University of Northampton

Nigeria’s new president, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, has promised to make security a top priority of his administration. In his inaugural speech he promised, among other things, to provide security personnel with better training, equipment, pay and firepower.

The new president has read the mood in the country well. A recent survey showed that 77% of Nigerians felt unsafe in their country.

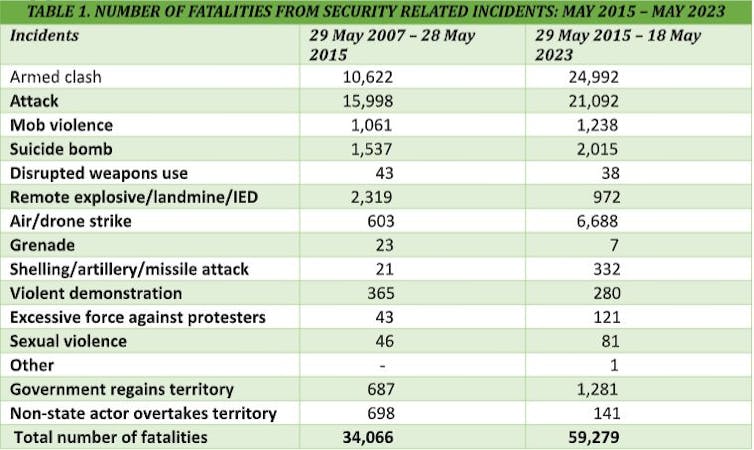

The security situation in Nigeria has deteriorated over the past eight years. Every region of the country is affected. Data compiled by this author, from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project shows that there were 59,279 fatalities from security related incidents between 29 May 2015 when President Buhari assumed office and 18 May 2023. This is opposed to 34,066 of such fatalities recorded between 29 May 2007 and 28 May 2015. (See table 1)

Boko Haram, which has existed in various forms since the 1990s, was for many years the country’s biggest security challenge. The insurgency, which started in Borno State, was concentrated in the north-east region. But now, other non-state armed groups are spreading violence all over Nigeria.

At least 7,222 Nigerians were killed and 3,823 abducted as a result of 2,840 violent incidents between January and July 2022.

Buhari made a number of promises to address Nigeria’s chronic security problems. But he failed to effectively address them.

As a sociologist with specialisation in civil-military relations, armed groups, criminology and security studies, peace and conflict management and human rights, I have been researching various aspects of insecurity in Nigeria. Based on this work, I outline urgent steps the Tinubu administration must take to turn the tide of insecurity.

It needs to audit the security budget allocation of its predecessor and take a close look at its implementation. This will help identify areas of inefficiency and corruption.

There is also a need for enhanced oversight and coordination among security agencies.

On top of this, the Tinubu administration needs to address underlying socio-economic factors that contribute to insecurity. Investment in education, healthcare and infrastructure development are crucial. So are job creation, poverty alleviation and inclusive economic growth.

Deteriorating situation

Buhari’s administration got off to a strong start in 2015 because it was able to secure arms from the US. This made an impact on the capacity of terror and insurgent groups in the north-east.

But, over his two terms, things got worse in every part of the country.

North-east Nigeria: ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province), in particular, remained resilient by continuously altering its operational strategies – using unmanned aerial vehicles, for example.

The group has attacked military and civilian targets in north-west Nigeria and remains a threat in the north-east.

The middle belt: This comprises states in the north-central and parts of north-west and north-east Nigeria. In Plateau State, Benue State and southern Kaduna, rural communities face attacks from ethnic militias identified by survivors as Fulani.

Most of the attacks are executed to dislocate locals. They destroy crops and farmlands, kill people and animals, burn houses, and make survivors afraid to return.

In 2018, these attacks claimed six times more civilian fatalities than the terrorist insurgency in the north-east.

Over 100 settlements in Plateau State and southern Kaduna have been occupied by Fulani groups and renamed after communities were displaced.

The issue has been raised in the National Assembly. And in 2020, the Plateau State government enacted a law against kidnapping, land grabbing, cultism and other violence.

But attacks continued in Plateau State communities.

North-west region: A new wave of banditry emerged in the region during Buhari’s administration. Initially it appeared to be driven by ethnic feuds between Fulani and Hausa groups. But militia groups who had taken refuge in forests also appeared to be involved.

Bandits attacked military locations, kidnapped hundreds of school students and abducted travellers. They even bombed a train and abducted passengers.

Numerous bandit groups now exist across the north-west region and Niger State. These groups are economically driven. When they are not kidnapping for ransom, they exploit the lack of state presence to impose taxes and protection levies on rural communities.

Kidnapping for ransom is currently a blooming criminal enterprise across urban areas in Nigeria and on major road networks.

South-east: Here too the situation deteriorated under Buhari. His lopsided appointments – known as Buhari’s 97% vs 5% – fuelled a violent secessionist threat in the region.

The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) championed the cause, and its leader, Nnamdi Kanu, was arrested.

But the group has remained resilient and, through threats and violence, it enforces days of sit-at-home in parts of the south-east.

Prison breaks: Eleven successful breaks between 2017 and 2022 have enabled 6,355 inmates, including high profile terrorists and bandits, to escape. My findings reveal that only 758 people have been rearrested.

Four successful breaks occurred during President Goodluck Jonathan’s regime, with 930 escaped and 274 rearrested or returned.

New administration’s to-do list

The security budget and its implementation must be audited to identify inefficiencies and corruption. Regular audits, citizen participation and whistle-blower protection would improve transparency and accountablity.

Security agencies need better oversight and coordination, along with performance monitoring and accountability. These measures can improve the impact of security budgets.

It’s also vital to address the socio-economic factors that contribute to insecurity. The country needs job creation, poverty alleviation and inclusive economic growth, particularly in areas affected by insurgency and insecurity.

Investment in education, healthcare and infrastructure will create opportunities that discourage criminal activities.

Inclusive governance is essential for peaceful coexistence and a sense of belonging. The government must also address the lingering crisis of displacement and occupation in the middle belt, and the secession agitation in the south-east.

Effective communication between communities and security agencies is essential.

The security sector must respond faster to early warning signs.

Finally, perpetrators of violence and their sponsors must be prosecuted.![]()

Sallek Yaks Musa, Lecturer, University of Northampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.