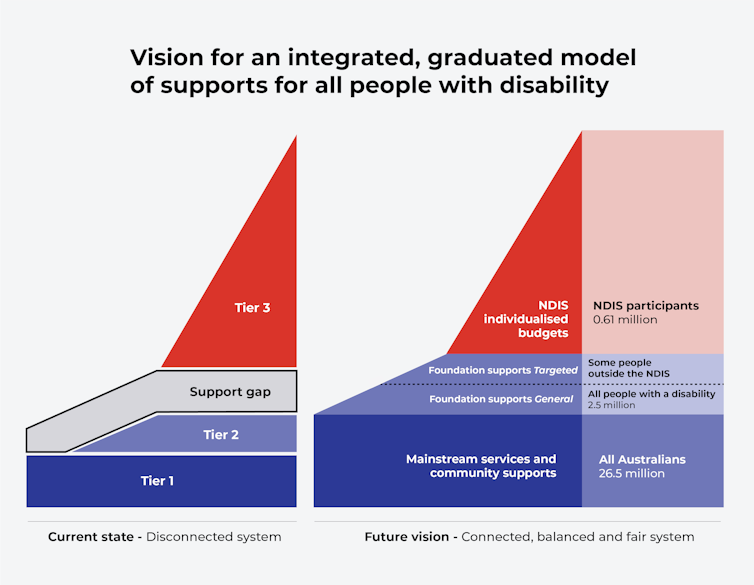

The long-awaited NDIS review has looked far beyond the National Disability Insurance Scheme, taking a bird’s eye view of disability services in Australia. Critical to the future of the NDIS are services for people with disability outside of the scheme.

More than 85% of the 4.4 million Australians with disability are not in the NDIS. As services to support them have shrunk in the ten years since the NDIS was introduced, they’ve been scrambling to join the scheme.

The very first of the NDIS review’s 26 recommendations is a separate tier of disability services, called “foundational supports”, outside the scheme and accessible to many more people with disability. This will sound familiar to those familiar with the scheme’s original design when it was proposed by the Productivity Commission.

What could this look like in practice? And has the review resolved the problem of woolly definitions around “reasonable and necessary” supports?

The states are on board

National Cabinet’s decision on Wednesday for the states and Commonwealth to split the funding of foundational supports promises some relief to the majority of disabled Australians who can’t get support from the NDIS.

Establishing foundational supports outside the scheme is the end of a long battle. The states have cried poor, while the Commonwealth has insisted the NDIS cannot be the only source of services to people with disability.

On the face of it, the states got a great deal at National Cabinet.

States and territories agreed to increase their NDIS funding cap by 4% and signed up to a capped contribution of A$10 billion over five years for foundational supports. The Commonwealth agreed to tip in billions to strengthen Medicare, which is itself a provider of foundational supports – another win for the states.

What that could look like

More foundational supports should mean all people with disability, including hundreds of thousands of children, can get the services they need. Many supports which have been sucked into the NDIS vortex and itemised at high cost, could be removed from the scheme and funded on a more sustainable basis.

For example, providing services through schools and early childhood centres means more children get early intervention. These children don’t need an NDIS plan but rather the reasonable adjustments these settings are already obligated to provide.

Making mainstream services available should curb escalating demand for the professional diagnoses and reports currently needed to get onto the NDIS.

It should mean allied health professionals can visit multiple children at one school, and children can spend more time in the classroom.

More foundational supports will help the NDIS budget, too. If more disability services are available to people outside the NDIS, fewer people with disability will have to join the scheme to get what they need. It should mean people with higher intensity needs will be directed into the NDIS where they can get specialised services.

What about ‘reasonable and necessary’ supports?

The NDIS review found a lack of clarity about what supports should be considered “reasonable and necessary” was at the heart of many of the scheme’s problems. The review panel wrote:

It has contributed to a breakdown in trust between participants and the NDIA. It has also placed pressure on the sustainability of the scheme […] The criteria for reasonable and necessary supports were deliberately kept broad, to make sure supports can be tailored to the individual.

Foundational supports, for people outside the NDIS, are the sorts of services best funded through grants, contracts or government infrastructure. It would be neither practical nor cost effective to fund them on an individual fee-for-service basis.

In contrast, reasonable and necessary supports, for people in the NDIS, are more targeted, sometimes more specialised, and often more intensive. These are services such as attendant care at home, support with personal care, access to a range of therapies, and one-off costs such as assistive technology or home modification. These supports need to be tailored to the individual. This lends itself to individualised funding.

Having both foundational and NDIS supports should make life much better for Australians with disability – but only if the federal government announces reforms to create “NDIS 2.0” and foundational supports with ongoing funding, rather than an uncertain series of short-term project grants.

Meaningful support

Exactly what is reasonable and necessary remains undefined after this year-long review, but a new landscape of disability services should imbue the phrase with fresh meaning. Instead of being an ambiguous and threatening concept, a well-implemented level of funding should provide what is necessary for an Australian with disability to pursue their life goals – taking into account the foundational supports available outside the NDIS.

Aside from outlawing certain expenditure (for example, rent, groceries and utilities) and ensuring NDIS funds do not duplicate costs within the scope of other systems, what is reasonable and necessary becomes a simpler matter of fairness and equity. It is not a dehumanising debate about what you can and can’t have.

That is a disability scheme worth fighting for.![]()

Sam Bennett, Disability Program Director, Grattan Institute and Hannah Orban, Associate Disability Program, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.