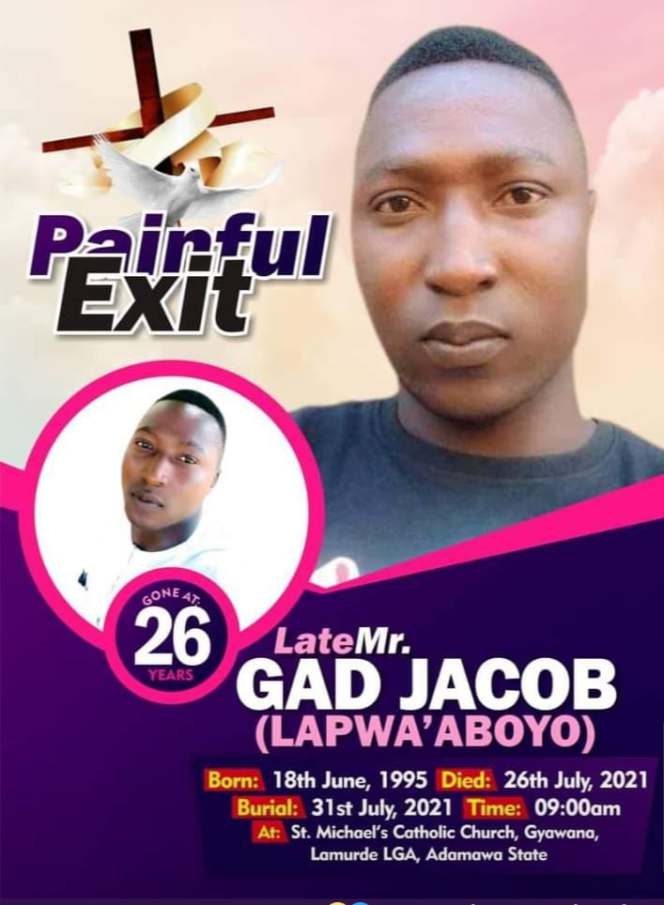

When Gad Jacob jumped on his motorcycle in mid-July 2021, to head home after a shift at Dangote Sugar Refinery, Nigeria’s biggest sugar factory, he had no idea it would be the last time he would be making the journey.

As the 26-year-old wound his way through Numan, a sleepy town on the outskirts of Yola, the capital of Adamawa State, he encountered a roadblock.

Dozens of youths were preparing to protest against the activities of the Dangote Sugar Refinery, the factory where Jacob worked.

Dangote Sugar Refinery had been accused of denying local people permanent jobs and exploiting its thousands of casual workers.

As Jacob tried leaving the scene, one of the protesters seized the license plate of his motorcycle, forcing him to stay,

With time, the crowd grew large and became restless, chanting slogans and preparing to march to the refinery’s entrance.

“There was no violence,” said Victor Jeremiah, one of the protesters. “We were simply shouting outside their perimeter fence.”

As tension between the protesters and the refinery’s officials grew, armed soldiers were invited to the scene.

The incident that followed as soon as the soldiers arrived has remained an object of dispute till date.

The military, on its part, claimed youths attacked the troops with machetes and tried to break into the factory.

To stop the youths from breaking in, the soldiers responded with “non-violent” means, firing warning shots into the air and using tear gas to repel the crowd.

According to a statement from the refinery managers, known by the acronym DSR, three people sustained minor injuries in the fracas, and nothing more.

However, a dozen eyewitnesses, backed up by medical documents, photographs, police statements, and an autopsy obtained by reporters, told a very different story.

By these accounts, most of which had never been reported before, at least 12 people were injured that day. The injured include five protesters who were allegedly shot by soldiers. One of them, Jacob, was killed.

A bullet tore through his calf, leaving him in a pool of blood on the road. He was taken to a specialist hospital for surgery, but died there 10 days later. An autopsy found the cause of death to be a bone marrow embolism caused by a gunshot wound which had fractured his right leg.

DSR, which supplies its products to major global brands like Coca-Cola, Unilever, Nestlé, Cadbury, and Pepsi Co., appeared to shrug off the incident, not mentioning it in the company’s annual report for the year.

The company, in its 2021 update to the world’s largest sustainable business initiative which the United Nations backs, made no reference to the protests or the allegations that casualties were recorded.

Speaking on the incident, Philip Jakpor, director of the Renevlyn Development Initiative, a Nigerian organisation that seeks to challenge corporate impunity, said, “No firm can be greater than the state.”

DSR did not respond to multiple requests for comments on the incident prior to the time this article was published.

No one has been prosecuted in relation to the events of July 15, 2021, the day the incident happened.

The Nigerian military denied any wrongdoing while the protest went on.

Major General Jerry Akpor, the Defence Headquarters’ spokesman at the time, said an internal investigation was carried out, but declined to give details.

Brigadier General Tukur Ismaila Gusau, the forces’ current spokesperson did not also give any reply to requests for comment.

‘LET HIM DIE’

Nadiye Obasanjo, a 27-year-old delivery driver, said he was standing on the sidelines watching the protests outside the DSR factory when he was shot in the stomach.

He collapsed onto the road, where he lay for hours before help arrived.

“Some soldiers wanted to take me to the hospital when they saw the bullet wound,” Obasanjo recalled.

“But their superior stopped them, saying “Let him die, drop him there”.”

Obasanjo subsequently had an emergency surgery on his gut and spent four months in hospital recovering, according to medical records and photographs. Those memories are still etched in his flesh, where a huge scar bisects his body from his chest down to his stomach.

Obasanjo said his digestive system has never been the same since he got shot. He now eats solid food in pain.

Presently, he survives on mashed vegetables and pap, a type of bland corn mush eaten as a side dish in many places in Africa. The pain from his scars now also prevent him from working on the small farm he inherited from his father, where he grows rice and soybeans.

“I have not been able to take care of it myself because I can’t bend for a long time without pains in my back area. I have to pay manual workers,” Obasanjo said.

JUSTINE IGNATIUS WAS SHOT IN THE CALF

Justine Ignatius spent two months in the hospital after being shot in the calf while protesting. The surgery to remove the bullet left him with one leg shorter than the other, dashing his dreams of one day becoming a soldier himself.

Ignatius now wears shoe lifts to help address his uneven height.

“I still feel pain whenever I walk,” the 25-year-old told a reporter who visited his modest one-bedroom home.

“My leg cannot do what it used to do. If I take off my shoe, I walk haphazardly without it.”

AUGUSTINE PHILEMON AND PETER AMOS

Two other protesters, Augustine Philemon and Peter Amos, were also shot that day, according to their accounts, the testimony of other witnesses and medical records sighted by reporters.

Amos said he was shot in the back as he tried to escape the teargas that troops fired at the crowd.

“We had planned to stand face-to-face with the soldiers, but when we saw the teargas we started dispersing,” Amos said.

“That was when I was hit by a bullet while trying to run back.”

For others, the scars left by the incident are more than skin deep.

SPECIAL JACOB AND HER DAUGHTER

Special Jacob works 12-hour shifts waiting tables in the canteen at the DSR factory, not far from where her husband was shot. Because she is only a casual worker her hours are unpredictable and she is paid very little, leaving her struggling to provide for Success, her daughter.

Only four when her father was shot, Success has been plagued by nightmares in the years that followed, sometimes dreaming that she is being chased by his killers.

“My daughter sometimes wakes me up to tell me that her father is in the room. And when that happens, I begin to feel his presence,” Special told a reporter in the living room of her small home, now largely empty after she was forced to sell her furniture to pay off debts.

“We have to keep pushing,” Special said. “I have to be a father and mother for my daughter.”

TOOTHLESS UN GLOBAL COMPACT

DSR is one of the most profitable companies listed on the Nigerian stock exchange. Originally state-owned, the facility was bought by Aliko Dangote — Africa’s richest man with an estimated fortune of $10.3 billion — more than two decades ago.

As the largest of three sugar refineries in Nigeria, the most populous nation in Africa, DSR has made huge profits in recent years.

In 2023, the company’s profits after tax soared to N73.7 billion ($68.2 million), a 35 percent increase on 2022’s N54.7 billion after tax profit.

For the people of Numan and its environ, the refinery is both a blessing and a curse. Though it employs over 6,000 people more than any other company in the region, some workers have accused the company of being poorly treated. Protests first erupted in 2017, when the factory laid off some 3,000 people, and resentment between both parties has continued to soar ever since.

In June 2021, DSR got a restraining order to stop youth leaders who were advocating for more jobs for local people from entering its premises. This led to some soldiers being permanently deployed to guard the refinery. A month later, the deadly protests ensued.

DSR presents itself to customers and investors as a socially responsible company. Anyone driving through its front gates is greeted by a banner proudly displaying the logo of the UN Global Compact, the world’s largest initiative for promoting sustainable business.

Launched by the United Nations in 2000, the UN Global Compact (UNGC) brings together more than 13,000 member organisations from 162 countries. Companies that sign up for the agreement must submit reports every year guaranteeing that they are not complicit in human rights, labour, or environmental abuses and outlining any incidents in their operations.

The 2021 submission by DSR’s owner, the Dangote Group, made no mention of the protests, the allegations of poor treatment by workers — or the violence of July 15.

“There were no reported cases of violation of human rights in any of our business operations,” said the report covering that year, which was accompanied by a letter from Aliko Dangote praising his group’s track record.

This statement appeared to ignore the accounts of eyewitnesses and official sources. The day after the protests, local media quoted a spokesperson for the police as saying five people had been taken to the hospital with bullet wounds after soldiers fired on protesters. This claim was accompanied by photographs of a wounded protester.

Three days later, the governor of Adamawa State, Ahmadu Fintiri, was filmed visiting the patients with gunshot wounds at Lamurde General Hospital.

“The military have gone too far,” the governor said in an interview with TVC News, calling for restraint by protesters.

A spokesperson for the UNGC declined to comment on the findings made by this article, saying only allegations made against its members can be reviewed by its offices.

Penelope Simons, a law professor and human rights expert at the University of Ottawa, said the UNGC had proved itself toothless when faced with complaints of abuses by other members in the past.

“I certainly don’t see it as an effective mechanism in any way,” she said.

The Nigerian branch of global accounting giant PricewaterhouseCoopers did not mention the protests in its 2021 audit of DSR, one of the thousands the firm conducts every year to ensure that companies’ labour, environmental and financial practices are up to standard.

The audit notes that people had made complaints about pollution and the lack of employment opportunities for the locals. But it makes no mention of the demonstrations or the ensuing violence, saying only that the “grievances were promptly addressed and closed out”.

According to the victims and community leaders, DSR has never acknowledged their complaints or paid any compensation. The medical bills of the 12 people who were injured, as well as the funeral rites and autopsy of Jacob’s husband’s body, were all paid for with monies raised by the community.

“Since I lost my husband it has been difficult … especially with the bills I have to pay,” said Jacob.

“The financial burden has been huge on me and my child is feeling the effect because I spend more time at the refinery where I work without much time to see my daughter.”

A spokesperson for PwC Nigeria also declined to comment on the issue.

INTERNATIONAL INVESTORS

The accusations of human rights and labour violations at DSR are not just a problem for the refinery. They also impact its customers, which include the Nigerian branches of some of the world’s largest food and beverage companies.

DSR lists Nestlé, Coca-Cola, Unilever, Cadbury, and PepsiCo — all members of the UNGC too — among its clients. All of these food giants claim their products are sustainable, with no human rights or labour abuses in their supply chains.

DSR’s top customers in 2021, according to a data that was recently made available, were a local franchise of Coca-Cola known as the Nigeria Bottling Company and the Seven-Up Bottling Company Limited. Neither of them replied to requests for comment.

Simons said it was difficult to hold companies liable for alleged abuses in their supply chains because they operate through different companies.

“A corporate structure hides off liability in different subsidiaries,” she explained.

European and US investors, who have poured millions of dollars into DSR’s operations, are also required to conduct due diligence to make sure they do not finance human rights abuses under rules laid out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

One of the investors is Dutch asset managers Trustus Capital Management BV, which as of the end of last year (2023) owned more than 14 million of DSR’s shares.

Figures from Trustus’ annual reports show that between 2019 and 2021, the fund managers received more than $192,000 in cash dividends from the sugar company.

Marco Balk, the company’s portfolio manager, rejected the evidence of rights abuses collected by the authors of this article, saying the accusations were not “corroborated with evidence.”

He also noted that the Nigerian military and DSR had “refuted key elements of the story, particularly the use of lethal force and the reported fatality”.

Another major DSR investor, The Netherlands-based Robeco Institutional Asset Management BV, which owns €563,000 worth of shares in DSR as at the end of 2023 financial year, said the protests had not been flagged by their data providers and pledged to investigate.

US asset managers Global X Management Company LLC and Parametric Portfolio Associates also both held millions of shares in DSR before and after the July 2021 protests. Both declined to comment.

‘THEY BEAT ME MERCILESSLY’

The dozen people hurt on July 15, 2021, were not the only ones claiming to have suffered losses as a result of the demonstrations.

Pwavi Philip, a farmer on DSR’s sugar plantation, said she was beaten by troops who accused her of spying on the company for the protest organisers.

Two days after the shootings, she claimed she was accosted by four soldiers who were guarding DSR’s facilities as she made her way through the plantation back to her plot.

“I told them I was going to the farm, but I was ordered to get on my knees,” Philip said.

“I tried to explain to them that I was a farmer on the Outgrower Scheme. At that point, they beat me mercilessly.”

She said the guards hit her with rifle butts and stomped on her with their boots, breaking her arm in the process. Pictures from the time show her arm in bandages, though Philip said she turned to a traditional healer when she could no longer afford her medical expenses.

Two years on, the arm still hurts when she labours on her farm.

‘CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILTY’

The Dangote Group has long worked with Nigeria’s police and military in the area of philanthropy.

Rather than employ its own security, however, the company relies on state forces to protect its assets, which it funds as part of its corporate social responsibility.

In 2018, one of the group’s other companies, Dangote Cement, bought 150 cars that were worth $800,000 for the Nigeria police, according to its annual report.

At the time, the force’s Inspector General said it was the largest single donation ever made by a private sector company.

Over the past five years, the Dangote Group has built training facilities for the police, paid for its training programmes and sponsored its officers to deliver protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It has also made cash donations to police commands in towns where its factories are situated.

DSR’s other corporate social responsibility initiatives have, regrettably, received less attention.

These include the Government Day Secondary School in Gyawana, one of the surrounding communities near the refinery, which DSR said it gave N33 million ($43,157) in 2020 to build three blocks of classrooms. The company also claimed it gave the school another N27 million ($35,303) for what it called “stakeholder engagement”.

“The company’s investment in the school is a part of its corporate social responsibility and not legally obligated to support the school,” the company said then.

When this articles authors visited the school late last year, however, they found many of the classrooms in ruins. In some places, the roofs had caved in, while the blocks built with DSR’s funds had no doors.

Knee-high weeds cracked through the floor of the school’s dilapidated toilet. Chief Amos Oseni, one of the community’s chiefs, said the facilities no longer work, and that hundreds of students who attend the school have been forced to relieve themselves in surrounding bushes.

“We’ve brought this to the attention of the company. Still, they’ve simply ignored us,” Oseni said.

This report was produced with support from JournalismFund.EU