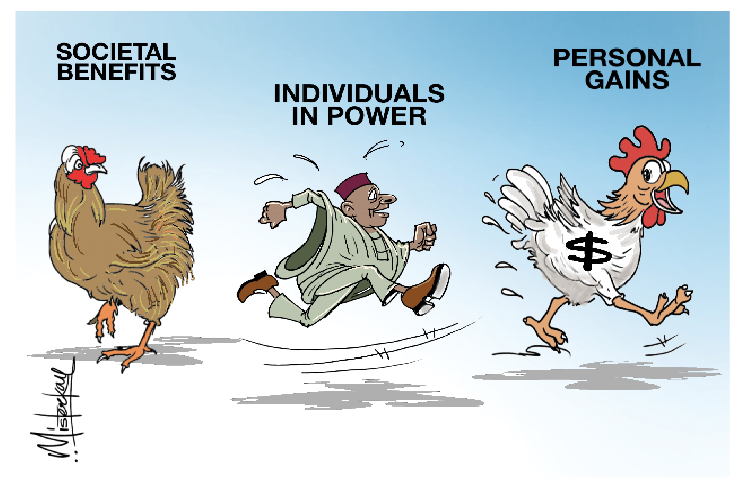

In Nigeria, public policies frequently miss the mark, leaving their intended beneficiaries wondering where the promised benefits went. Large-scale initiatives, from economic reforms to infrastructural projects, often falter before they even take off. The underlying reason for this recurrent failure isn’t usually a lack of ambition or well-meaning intentions – it’s something deeper. That something is agent interest, a concept rooted in public choice theory, which explains how individuals in power pursue personal gains rather than societal benefits. In a context like Nigeria’s, where corruption is rampant, agent interest has proven to be one of the greatest obstacles to achieving real policy change.

The failure of public policy is not merely a reflection of inefficiency or poor governance. Public choice theorists such as James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, and Mancur Olson have long argued that people in positions of power are not angels or altruistic actors but self-interested individuals responding to the incentives around them. When these incentives push officials to enrich themselves or their allies at the expense of the public, policies – no matter how well-designed on paper – fail to deliver. The most successful policies are often hijacked by those entrusted to implement them, diverting funds, delaying projects, and ensuring that resources meant for public welfare end up in private pockets.

Although the dynamics of agent interest are not unique to Nigeria, but the country’s weak institutional framework and entrenched corruption make them more pronounced. In a system like ours where accountability is lacking, agents – whether politicians, civil servants, or contractors – respond to the incentives around them. If the consequences of misusing public resources are minimal and the rewards of doing so are significant, public policies will always face an uphill battle.

The Mechanics of Agent Interest

Consider a scenario where a state governor allocates funds for the construction of a major road project that is supposed to connect rural areas with urban centers. This road promises to open up markets, enhance trade, and bring vital services to the rural population. However, instead of ensuring the timely completion of the project, the governor – or the agents involved in the project – diverts the funds for personal enrichment. They inflate the costs, give contracts to politically connected but unqualified contractors, and pocket the difference. As a result, the road remains half-built, and the farmers who would have benefitted from it are left stranded.

This behavior is exactly what public choice theory seeks to explain. that individuals in the public sector – just like those in the private sector – are driven by self-interest. Their primary concern is not delivering on the promises made to the electorate or improving public welfare, but securing financial rewards, political support, or other forms of personal gain.

Mancur Olson’s work on “concentrated benefits and dispersed costs” provides insight into how agent interest plays out in practice. According to Olson, when a policy benefits a small group of individuals – such as corrupt politicians, contractors, or bureaucrats – while the costs of that policy are spread across the entire population, those individuals have a strong incentive to exploit the system for personal gain. For example, a government subsidy designed to ease the burden of the masses might be hijacked by well-connected elites who siphon off funds or manipulate the system, leaving the intended beneficiaries with little to no relief. The broader public bears the collective cost of this exploitation, while the agents involved reap concentrated rewards.

Weak Institutions: The Fertile Ground for Agent Interest

While agent interest is a natural human tendency, its corrosive effect on policy outcomes is magnified when institutions are weak or ineffective. Institutions, in this context, refer to the formal and informal rules that govern public decision-making, accountability, and enforcement. These include laws, regulatory agencies, courts, and oversight bodies. Strong institutions are supposed to act as a check on individual behavior, ensuring that public servants and politicians remain accountable to the people they serve. When these institutions are compromised, it becomes easy for agents to act in ways that serve their personal interests instead of the public good.

In Nigeria, the lack of strong, independent institutions has allowed corruption to flourish unchecked. Take the example of Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), an agency tasked with combating corruption and holding public officials accountable. While it has achieved some success in prosecuting high-profile cases, it is often accused of being politically influenced or selective in its enforcement. Political interference, lack of resources, and inconsistent application of the law undermine the agency’s effectiveness. This lack of accountability creates a system where public officials feel free to siphon off public funds with little fear of retribution.

Similarly, procurement processes in Nigeria are often marred by lack of transparency and weak regulatory oversight. Billions of naira allocated for infrastructure projects or social programs often disappear into the hands of well-connected individuals or companies. The absence of stringent auditing mechanisms, independent oversight committees, and robust enforcement of anti-corruption laws makes it incredibly easy for agents to divert public resources for their own benefit.

This situation creates a vicious cycle: weak institutions allow agent interest to thrive, and the unchecked pursuit of personal gain further weakens institutions. Over time, Nigerians become disillusioned with the government and its policies, believing that there is no point in hoping for change because the system is rigged in favor of a small elite.

The Path Forward: Aligning Incentives for the Public Good

Addressing the issue of agent interest requires more than just reforming institutions—it requires a fundamental shift in how Nigerians view public service and governance. If the country is to break free from the cycle of corruption and policy failure, there must be a concerted effort to realign the incentives that drive the behavior of public officials and citizens alike.

First and foremost, institutional reform is critical. Nigeria needs stronger, more independent bodies to oversee the implementation of public policies. The creation of transparent e-governance platforms, real-time monitoring of public spending, and rigorous auditing of public projects are some of the steps that can be taken to reduce opportunities for corruption. Public servants should face real consequences for mismanaging public resources. The EFCC and ICPC must be given the tools they need to hold individuals accountable, no matter their political affiliation or social status.

Second, civic education and public awareness are essential for changing the mindset of both the electorate and those in power. Nigerians need to recognize that policies fail not because of a lack of resources, but because resources are being stolen or misallocated. An informed electorate is more likely to demand better from their leaders and less likely to accept short-term handouts or empty promises. The media, civil society organizations, and educational institutions all have a role to play in fostering a culture of accountability and transparency.

Finally, cultural change is needed. In Nigeria, wealth is often celebrated regardless of how it is acquired. The “big man” syndrome—the tendency to revere individuals who accumulate wealth, even if it comes from corrupt means—perpetuates the idea that self-interest and exploitation are acceptable. A shift in cultural values toward integrity, honesty, and public service is necessary if the country is to break the stranglehold of agent interest.