Richard Bean, The University of Queensland; Frode Weierud, CERN, and George Lasry, University of Kassel

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Biafran conflict in 1970.

The trigger for the conflict was the proclamation by Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu on 30 May 1967 that Biafra had become a republic. After 30 months of war, Biafra surrendered and was once again incorporated into Nigeria.

According to the author John de St Jorre, between half a million and a million Nigerians died, mainly from starvation, during the war.

Through the efforts of their roving diplomats during the war, Biafra achieved recognition from the states of Tanzania, Gabon, Haiti, Ivory Coast, and Zambia. But the fledgling state struggled to secure wider diplomatic support. It also found it difficult to purchase weapons and smuggle them into its controlled territory via airlift.

The efforts of these diplomats have recently come to light through the decryption of telexes sent from Portugal to Biafra during the war. Telex, short for teleprinter exchange, was a method for transmitting messages electronically over land lines or radio. Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, had become the centre for Biafran diplomacy in Europe because the government of Portugal under António de Oliveira Salazar supported Biafra with air landing and communication privileges. Paris and London were also key centres for Biafran diplomats.

In our paper we set out what was in the encrypted messages, and how we solved them. Three of us worked on the project, each with different disciplines – a mathematician, a computer scientist and a radio technologist. We used manual and computerised cryptanalysis methods to decipher a series of transposition ciphers sent by Biafran officials in 1968 and 1969.

It took us three months to figure out how the encryption worked and what keys were used. We also needed to read about the context of the war to understand and interpret the messages. The historical figures were unfamiliar to us and many codewords were used for people, countries and objects.

In the end, the decrypted messages provided a treasure trove of information about how men and women working for the breakaway state in Europe tried to garner support for Biafra from afar during the war.

Decades long decryption project

At the time, the Biafrans sent some of their messages in plain English text and made some extra effort to encrypt some in order to ensure that at least casual eavesdroppers couldn’t read the encrypted ones. However, they made mistakes which meant that professional as well as amateur eavesdroppers could have read them.

We know of at least two professional organisations that did intercept them: the Swedish signals intelligence agency, the FRA, and the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Some were also intercepted by at least one amateur radio operator, Frode Weierud, in Oslo, a co-author of our academic paper.

At the end of July 1969 Weierud discovered a signal in the shortwave band transmitting a regular message in radioteletype: “This is Biscaia testing to LDA/3”.

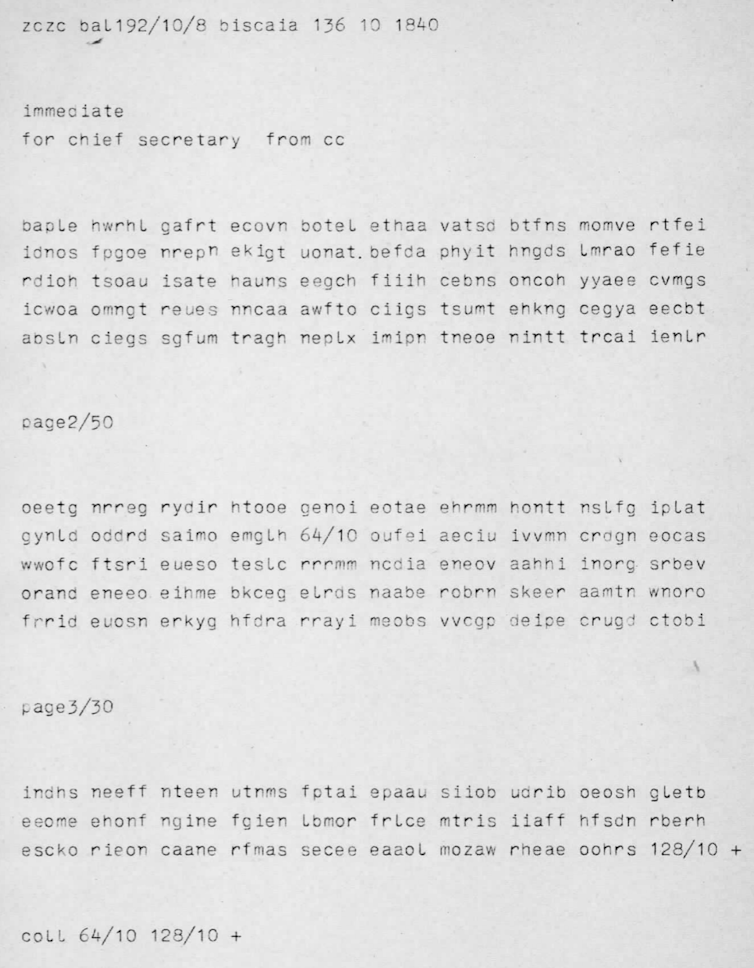

Using teleprinter devices, he was able to intercept a series of messages from the station “Biscaia”. The messages were initially in understandable English, but soon they started arriving in ciphertext, in both five-letter and five-figure groups.

These messages were from a telex link between Biafra and Lisbon. During the war, Biafra had only one telex machine. It was the only communications link to and from the outside world. The machine was moved around Biafra depending on what territory was controlled.

The unencrypted, or “plaintext” messages sent over the link were often intended for wider distribution via Biafra’s public relations firm in Geneva, Markpress. The encrypted messages were between Biafran diplomats in European cities and the leaders of Biafra and were not intended for public distribution.

Although Weierud tried to decipher the messages in 1974 and wrote to a cryptography journal about them in 1978, the messages remained publicly undeciphered until he published them on his website in 2019. A Swedish signals intelligence veteran, Jan-Olof Grahn, also described the content of some messages in a 2019 book.

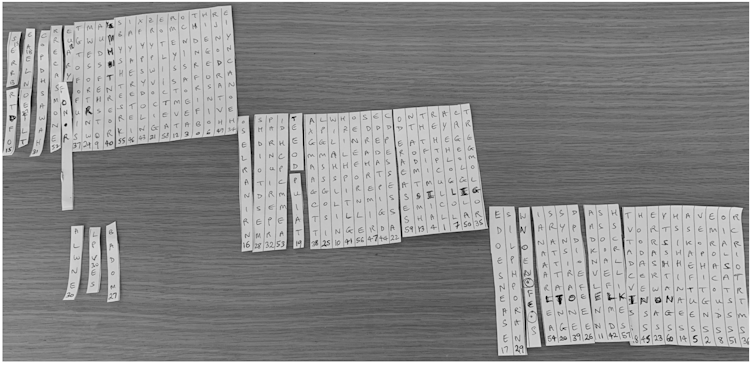

After Weierud published the messages, I joined him, as did George Lasry, a computer scientist from Israel, to decipher the messages. This was a difficult task as the cipher system was unknown. In fact, we used advanced computer algorithms, and also needed to improve them, to decipher some of the more challenging traffic. We also had to resort to manual methods at some points, writing out the letters on strips of paper and rearranging them by hand to form readable English.

The task took many hours across all the messages. In general, the task for a code breaker is easier when more “ciphertext”, or encrypted messages, are available. The Swedish intelligence agency would have made short work of the messages, given the great number of messages intercepted by their superior equipment and the regular nature of the messages.

For instance, each message begins with the word “SECRET” followed by the name of the sender and recipient, which is given in both plain and ciphertext. If the codebreaker knows a particular phrase like this, called a “crib”, occurs in the plaintext, this can make the process of deciphering much easier.

Being able to see the original texts allows for a more accurate record of history, as the messages offer a contemporary, first person view into the conflict. Later accounts may well be whitewashed or self-serving by contrast.

What we found

The broad subjects covered by the messages included travel arrangements, arms deals, expenses and public relations.

The longest message was from Austine Okwu, the Biafran representative to Tanzania, to Colonel Ojukwu about taking the Biafran cause to the United Nations General Assembly. Other key characters in the messages were Christopher Mojekwu, described as “Ojukwu’s closest confidant of all”, and Chris Onyekwelu, Ojukwu’s brother-in-law.

One of the messages referred to members of the delegation bringing Biafra into disrepute by not being able to pay their hotel or telephone bills. The leaders urged frugality in the message.

Other messages referred to logistics, travel and shipments. For instance, one message from Mojekwu to Ojukwu referred to a weapons transfer and contacting “Achebe” – perhaps referring to the famous author.

Another message from October 1969 referred to the possibility of flights for salt and meat, and the extension of a hospital under the direction of Edgar Ritchie, an Irish obstetrician.

What next

Many of the cities and characters are still obscured by acronyms or codewords and remain to be identified, such as “HY” and “Chabert”. On the other hand, we were able to identify a whole series of other codewords concerning places because the plaintext described public events using codewords.

The key to the solutions was increased by computer power, storage, improved algorithms and international collaboration. The five-figure ciphers remain unsolved for any readers who want a challenge; although if a “one-time pad” encryption system has been used correctly, they may never be solved. Such a system provides perfect security if certain conditions are met.

In contrast, the system used would not have provided security to a determined eavesdropper. This gave us a rare window to see diplomatic communication – often protected by strong encryption – in action. To listen in, intelligence agencies either break the codes or insert a “backdoor” into the machines used.

Apart from being a fascinating project, we also believe the messages we decrypted provide a useful complement to the later written accounts of the participants in the war.

Richard Bean, Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Frode Weierud, Electronics engineer, CERN, and George Lasry, Ph.D., the DECRYPT Project, University of Kassel

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.