Jan Machielsen, Cardiff University

On International Women’s Day this year, Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon apologised at Holyrood to “all those who were accused, convicted, vilified or executed under the Witchcraft Act of 1563”.

Her apology follows a social media campaign for an apology, legal pardon and national monument for more than 2,000 people executed between 1563 and the act’s repeal in 1736. This has been led by two new organisations set up in the wake of the #MeToo movement: Remembering the Accused Witches of Scotland (RAWS) and Witches of Scotland.

Witchcraft monuments dot the European countryside. They have been erected at many sites of intense witch-hunting such as Cologne and Bamberg in Germany, and in the French and Spanish Basque Country.

Pardons are more of a novelty. In 2008, the Swiss canton of Glarus pardoned Anna Göldi, whose execution for witchcraft in 1782 was Europe’s last. In January, Catalonia became the first territory to pass a blanket pardon of all its witches, with plans to rename streets in their memory.

Scotland was the epicentre of witch-hunting in the British Isles. Wales and Ireland saw a negligible number of executions, whereas Scotland executed at least 15 times as many witches as England relative to its population.

In 1597, King James VI of Scotland (and later I of England) became the only European monarch to publish a treatise defending the reality of witchcraft. A supposed sect of North Berwick witches had allegedly sought to sink the king’s ship upon his return home from marrying Anne of Denmark.

These 1590 trials witnessed exceptional levels of torture and James interrogated some suspects himself, becoming convinced of the satanic conspiracy when a suspect “declared unto him the verye woordes” which he had exchanged with his new queen on their wedding night.

The king, a proponent of divine right monarchy and a leading claimant to the English throne, was delighted to hear that he was indeed “the Lord’s annointed” and “the greatest enemy the Devil hath in the worlde” and arranged for a pamphlet to be published in London to let his future subjects know.

Scottish historians and institutions have long confronted this bloody history. The 2003 Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, a database which documents all known accused, remains a vital resource. The University of Glasgow has made many texts available online, while the National Galleries organised a deeply impressive exhibition of witchcraft engravings.

Most recently, the National Trust for Scotland published a report on the connections of its properties to the witch-hunts. A BBC Scotland podcast series has also helped raise public awareness.

Prejudice, misogyny and grievance

Given the great strides that have already been made, is a pardon the next step? Pardons have traditionally been reserved for miscarriages of justice where the victims or their immediate descendants were still alive.

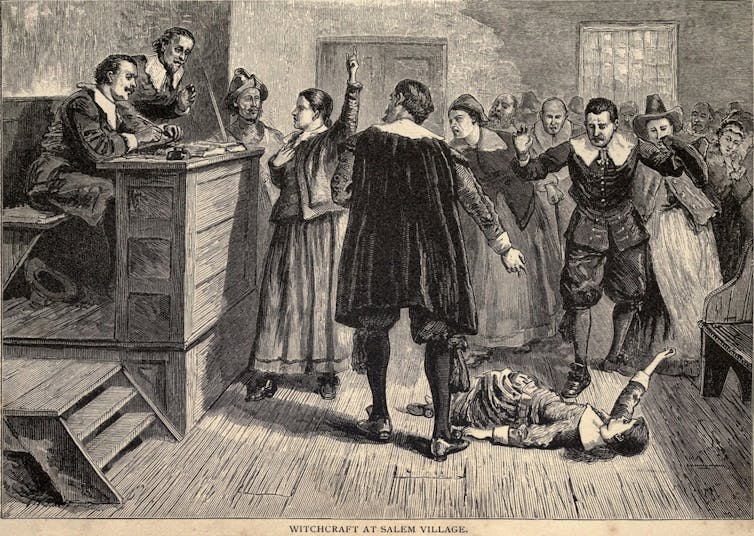

What makes the 1692–93 trials in Salem, Massachusetts, unique within the wider history of witch-hunts is the swiftness with which public opinion changed. Within a matter of years, the first survivors had their names cleared and received financial compensation, providing a foundation on which later posthumous pardons were built.

As Sturgeon noted in her speech, Scotland has already offered a general apology and automatic pardon to gay men convicted prior to 2001 under discriminatory laws. The case for a pardon, therefore, can appear straightforward. Witchcraft did not exist. Pardoning long-dead witches will not help them, but if we decide that it will help us as a society we should officially acknowledge the injustice.

The case for witch museums, memorials, even street names is similarly strong. They can foster reflection about the negative impact of our own biases and prejudices on others – especially the vulnerable “other” – in the present.

From a historian’s perspective, the case for an official apology is much more challenging, however. At a time when powerful politicians claim to be the victims of witch-hunts, historians are wary of the ways in which the past can be reclaimed to legitimise present grievances. Comparisons to the Holocaust or other modern acts of genocide are also deeply problematic.

We are also acutely conscious of the danger of official narratives. Nicola Sturgeon’s assertion that Scotland’s witches were killed “in many cases, just because they were women”, unconsciously evokes and rejects the memorable claim by Christina Larner, Scotland’s most famous witchcraft historian, that witches were accused not because they were women, “but because they were witches”. Indeed, one in six were men.

The deep misogyny of the witch-hunts is not in doubt, but the workings of the patriarchy were (and are) complex. It was also by no means the hunt’s only driver: the worsening climate, growing economic inequality and tensions within communities all played important roles.

We may also ask what the first minister was apologising for. If historians have learned anything in the past 50 years, it is that stronger states with greater central oversight such as England, France and Spain saw much lower levels of witch-hunting than weaker ones, like Scotland.

James VI may have approved of witch-hunting, but Edinburgh normally performed a more passive, enabling role, allowing local communities and elites to root out the witches in their midst.

Witchcraft accusations blamed a community’s ills – unexplained deaths, harvest failures, ill feeling – on a single, often vulnerable, individual, absolving the consciences of all those around her. Her confession and death showed that her neighbours had been right to mistreat her “because” she was an evil witch.

We should ask whether representing the witch-hunt as a “state-sanctioned atrocity” risks doing something similar. Early modern communities prosecuted witches collectively. It is facile to claim that only the state, or even only elites, were responsible; there is a potential witch-hunter in all of us. If the purpose of an official apology is to pin blame for the witch-hunt primarily on the Scottish state, then that would be precisely the wrong lesson learned.![]()

Jan Machielsen, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.