Sophie Lund Rasmussen, University of Oxford

The European hedgehog is in decline all over Europe. In Britain, the species is already deemed vulnerable to extinction having seen its population fall by at least 46% in the past 13 years to an estimated 500,000 animals.

I have researched what is causing their disappearance for a decade. This has involved several research projects at the University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit focused on optimising conservation strategies to protect wild hedgehogs.

One of these projects – the “Danish Hedgehog Project” – involved more than 400 volunteers collecting 697 dead hedgehogs from all over Denmark, where my research is based. My colleagues and I then studied how long these hedgehogs typically lived for and why they died.

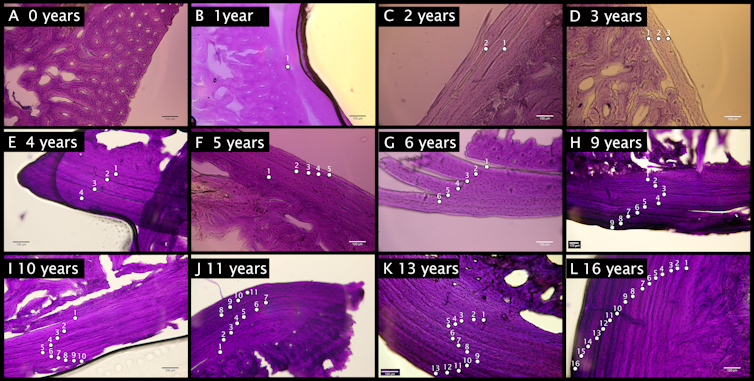

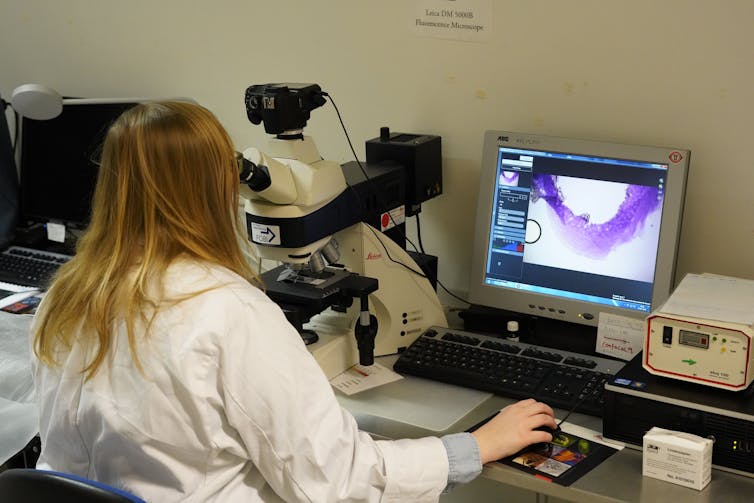

The method for ageing a dead hedgehog is similar to counting growth rings on trees. When hedgehogs hibernate over winter, their calcium metabolism slows down, which shows as a line of arrested growth in their jawbones. This allowed us to determine how old 388 of these hedgehogs were when they died.

We found the world’s oldest scientifically-confirmed European hedgehogs. The oldest, called Thorvald, was 16 years old and surpassed the previous record by seven years. Thorvald died in 2016 after being attacked by a dog, a sadly rather common cause of death for hedgehogs, but alongside the other hedgehogs we studied, he now contributes important knowledge on the mysterious lives of these animals.

The state of Denmark’s hedgehogs

A few more surprisingly old hedgehogs, aged ten, 11 and 13 years, were also collected. But on average, the Danish hedgehogs we studied only lived to around the age of two.

The male hedgehogs tended to live longer than females. Males lived to 2.1 years on average compared to just 1.6 years for the average female. This finding is uncommon in mammals and is likely caused by the fact that it is simply easier being a male hedgehog.

Hedgehogs are not territorial, so males rarely fight, and females raise their offspring alone. The high fitness cost of raising offspring alone may partly explain why the risk of death for female hedgehogs increases with age compared with a constant risk of death for male hedgehogs throughout their life.

Over half (216) of the hedgehogs had been killed when crossing roads. These deaths, 70% of which were males, also peaked in July during the mating season. Male hedgehogs tend to have larger home ranges than females and as they expand their range during the mating season, they will frequently cross roads. Research that I co-authored in 2019 found that the home range size of male hedgehogs in suburban areas around Copenhagen in Denmark increased fivefold during the mating season.

Of the animals not killed by road traffic, 22.2% (86) died in wildlife rehabilitation centres after having been found by the public either sick or injured and a further 21.6% (84) died from natural causes in the wild.

Low genetic diversity

We also investigated the impact of inbreeding on the life expectancy of European hedgehogs. My previous research found that the Danish hedgehog population has low genetic diversity, indicating a high degree of inbreeding. Low genetic diversity can reduce the fitness of an individual animal and may lead to several potentially lethal hereditary conditions.

Inbreeding can occur when hedgehogs are restricted in their search for suitable mates. The likelihood of inbreeding increases as their habitats become fragmented by roads, buildings, fences and railway tracks, and as population decline restricts the pool of potential mates.

Surprisingly, we found no association between the degree of inbreeding and age at death in our hedgehogs. This is interesting, as there is a general lack of knowledge on the effects of inbreeding in wildlife.

How you can help

Hedgehogs are increasingly inhabiting areas that are occupied by humans. But our study reveals that humans are the major drivers behind the decline of hedgehogs.

Many hedgehogs will only live long enough to take part in one or two breeding seasons. Yet our discovery of Thorvald and several other old hedgehogs suggests that their ability to avoid dangers such as cars and predators will improve if they manage to survive a minimum of two years.

There are several steps that you can take to help hedgehogs navigate the dangers they face. Hedgehog Street, a conservation campaign jointly funded by People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) and the British Hedgehog Preservation Society (BHPS), offers some useful advice.

For example, removing barriers between our gardens to create hedgehog highways will allow hedgehogs to move freely between gardens in search for food, nest sites and mates. This may reduce the need for hedgehogs to cross roads so often.

Making sure our gardens are hedgehog-friendly is another option. Log and leaf piles, or purpose-designed boxes called hedgehog houses provide safe and secure sites for breeding and nesting. Ensuring your garden has plenty of greenery will also attract insects, slugs, earthworms and snails for hedgehogs to feed on.

But it’s important to remove anything from your garden that can harm hedgehogs. This includes poisons, netting, garden tools, aggressive dogs, deep holes and steep edges around pools or ponds.

Any improvement in our knowledge of hedgehogs in the wild will also be important. The Zoological Society of London surveys Greater London’s hedgehog populations through its London Hogwatch project. And the BHPS funds the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative which offers universities, colleges and primary schools awards for completing actions to help hedgehogs thrive on their campus.

The BHPS and the PTES’ latest report on the state of Britain’s hedgehogs indicates that the decline in UK hedgehog populations may be stabilising in the urban areas. This could be due to the efforts of the public that have been inspired by these campaigns.

The fact that Thorvald lived to the age of 16 offers hope for the future of European hedgehogs. If we work together, we can save this charismatic species.![]()

Sophie Lund Rasmussen, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.