The landlocked nation in west Africa recently announced it was ending military cooperation with the US after 11 years. This was after the military in Niger overthrew the country’s democratically elected president.

Niger has been a strategic military partner of several countries, including the US, France, Germany, Italy and Russia. In addition to helping west African countries fight terrorism, these countries were also there to promote and secure their own economic and commercial interests.

Before the 26 July 2023 coup in which the Niger junta seized control, the US operated two drone bases and had more than 1,000 military personnel in the country.

As a scholar of the politics and security of west Africa and the Sahel, I have previously analysed the impact of foreign military presence, especially the US drone base in Agadez.

I argued in 2018 that the presence of the drone bases would not eradicate terrorism in the region. And indeed, six years on, terrorism has been on the increase in the region.

This is because of the lack of understanding of local conflict dynamics, inability to address the root causes of terrorism, and a disconnect between human rights adherence and counter terrorism.

How has the US fared?

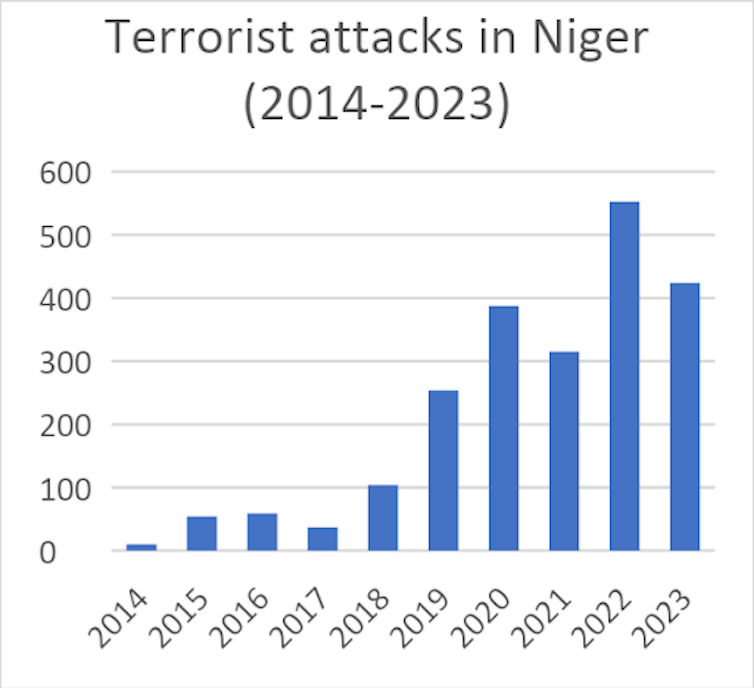

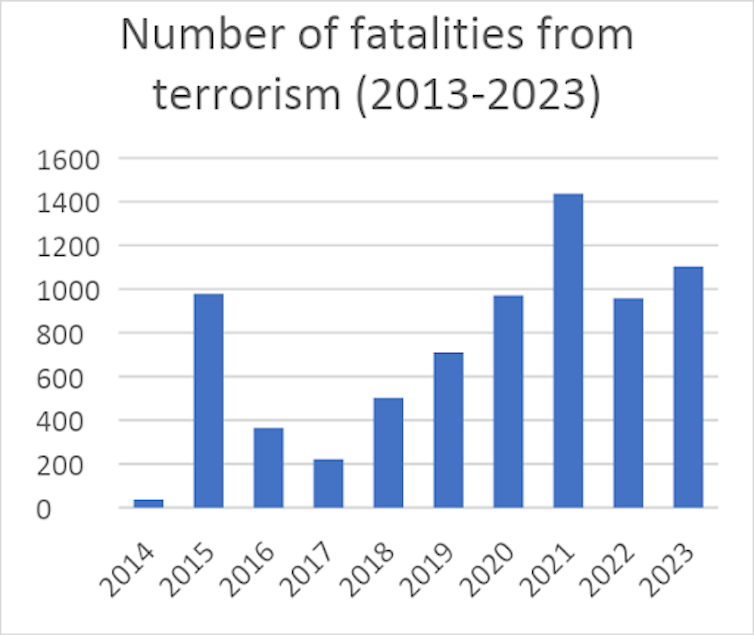

Using data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data – an independent, non-profit organisation collecting data on violent conflict and protest in all countries and territories around the world – I analysed the impact of foreign military presence and the US drone base on counterterrorism in Niger. The analysis is based on the number of attacks carried out by terrorist groups in the country and the resulting fatalities.

The tables above show that despite the US operation starting in 2013, terrorist activities and fatalities have steadily increased since 2014. In fact, the number of attacks has increased significantly since 2018 when the US opened Air Base 201 in Agadez.

My predictions that the drone base could worsen the security situation and position the country as a magnet for insurgency seem to have come to pass.

The military junta cited rising insecurity and declining economic prospects as reasons for taking power. The tables above show they were right that insecurity has been on the increase despite the presence of foreign military personnel in the country. Many Nigeriens who protested the presence of the US and France military in the country also raised similar concerns.

America’s success in the Sahel

While the charts above do not show any significant positive effect of the US in Niger, there are a few.

The US supported some of the countries in the region (Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Benin) to establish a joint task force to combat terrorism.

The Multi-national Joint Task Force was established in 1994 by Nigeria to curtail trans-border armed banditry in the Lake Chad Basin area. In 2015, the mandate of the task force was changed to combat terrorism in the region. The US played a role in establishing the platform.

In addition, the US provided logistics and advisory support to the task force and the now defunct G5 Sahel grouping. The US drone bases were particularly important for information gathering across the Sahel. The information was relevant to the counter-terrorism operations of the task force.

The US defence department also provided financial support to other foreign troops and groups involved in the fight against terrorism in the region. In 2018, for instance, the US provided $59 million to support and build the capacity of African partner states.

America’s failure in the Sahel

Despite some of the successes recorded, foreign military presence and the establishment of the drone base have not weakened terrorist organisations in Niger and the Sahel region more broadly.

In my opinion, three main factors explain the reasons for America’s failure in Niger.

First, there was too much emphasis on military operations without addressing the economic reasons for terrorism. Research has shown the link between poverty and terrorism. Poor economic prospects, unemployment and a large youth population have all contributed to the expansion of terrorist groups in Niger.

A recent report by the Lake Chad Basin Commission highlights the importance of non-kinetic (non-force) measures in counterterrorism. Terrorism in the region cannot be addressed militarily. The issues resulting in terrorism need to be addressed to reduce the incentives for people to join terrorist groups.

Second, the US and its allies did not fully understand the local dynamics of the country or the roles of traditional rulers in aiding or countering terrorist groups.

In my previous research, I found that political patronage played a role in the formation and growth of insurgent groups.

The same is the case in Niger and some other African countries. Local political dynamics, ethnicity and religion shape the scope and dimensions of terrorism. A military approach without corresponding dialogue with relevant local groups, especially traditional rulers, will not produce any significant positive outcome.

Third, the emphasis on human rights in the fight against terrorism is pushing Niger and other juntas to embrace Russia and China. The US and their allies routinely deny sales of specific weapons to African countries based on human rights records. In 2021, the US Congress blocked the sale of important weapons needed to fight terrorism in Nigeria. Russia and China, however, do not put such restrictions on weapons sales. Niger has been building stronger military ties with Russia lately.

Finally, some Nigeriens, analysts and experts believe the primary aim of the US and its allies in the country is not to fight insurgency but to promote their own interests. This was a message that resonated with the Nigerien public after the coup and which the military junta seized to garner support.

Insecurity and terrorism in Niger could be described as a “wicked problem” – complex and difficult to solve.

Some of the failings of the US are not its fault. But the US should look inwards and rethink its security alliances, making sure the will of ordinary citizens is catered for.![]()

Olayinka Ajala, Senior lecturer in Politics and International Relations, Leeds Beckett University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.