Rebecca Simson, University of Oxford

Many newly independent African countries in the 1960s inherited regional and ethnic inequalities in formal educational attainment. These new states bound together sub-national regions of diverse ethnic and religious communities. The regions differed in their exposure to missionary activity – the main vector in the spread of formal western education in the colonial era.

Inequalities in educational access increased the higher up the educational ladder one climbed. Access to university education was both extremely limited and highly skewed.

As access to higher education determined which people would come to hold some of the most important positions in society, politicians cared a great deal about how higher education spread. Given this context, how did regional inequalities in university access evolve after independence?

While several recent papers have highlighted considerable social inequalities in access to higher education in African countries today, there’s little work that looks at how and why such inequalities have changed over time.

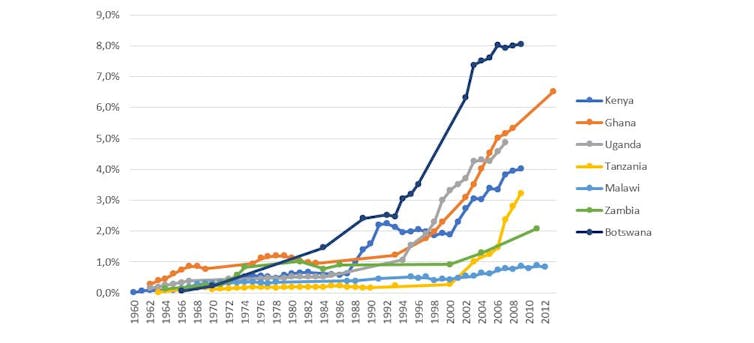

In a recent paper I therefore traced the regional origins of university graduates since the 1960s in seven African countries: Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. I constructed a measure of regional inequality for each country and examined some of the factors that influenced this inequality trend.

The results show that regional inequality fell in the first two decades of independence. However, from the 1980s regional inequality remained stagnant or grew across this group of countries. Inequality grew primarily because the main urban metropolises have been pulling ahead, leading to a growing urban bias in university access.

I used recent census data which contains information about where people were born and what level of education they attained. I grouped these people by their district or province of birth, depending on the administrative structure of the country. In Ghana for instance, people were grouped into the country’s ten regions, while in Kenya they were grouped into the country’s 47 current counties.

By grouping people by age bracket, and assuming that most people who attend university do so around age 20, I could then trace how the regional distribution of university education changed over time.

Slow start

University education was slow to develop across these former British colonies. The share of the population attending university in the late colonial era was extremely low.

Around the time of independence, Kenya had roughly 400 university students (1961), while Tanzania and Zambia had 300 students each (1963). The distribution of these scarce educational opportunities was regionally skewed. University attendance tended to be highest among those growing up in the main cities and in the regions with the most economic production (particularly cash crops and mining).

This historical legacy has been long lasting. On average, the regions with higher than average university attainment in the 1960s continue to have higher university attainment rates today.

Trends in access

But the picture is not all bleak. In the first decades of independence there was some catching-up by some of the lower performing regions within each country. The regional inequality trend for each of the seven countries shows that inequality fell in most countries in the 1960s and 1970s. In this period the number of university students was growing quite rapidly. Bursaries for students were generous and governments made some efforts to ensure regional balance.

In the 1980s many African countries ran into financial difficulties. Governments struggled to finance their largely public university systems. During this period, the rate of university expansion reduced. University access became increasingly competitive. This ended the period of regional convergence in university enrolment. Regional inequalities in university access began to grow again.

My analysis found that those best placed to access the highly competitive university system were increasingly those students born in the main cities where incomes were higher and parents more educated. Measures of regional inequality with the exclusion of the capital cities show there was no or very little growth in regional inequality since the 1980s. This shows that most of the inequality rise was driven by the capital city region.

In the 1990s many African countries reformed their university systems again by introducing or raising fees. They also allowed more private universities to establish themselves. This increased the number of students that could be educated and led to the rapid rise in university enrolment. But from the available data it seems that regional inequalities in university access have remained high or risen further.

Concentrated in cities

There are many reasons for this continued growth in inequality in access. The most important factor is one that’s difficult for policymakers to address. The census data shows that the focus countries have a considerable rate of rural-urban migration. These migrants are a small share of the university educated. As a result, university graduates are increasingly concentrated in the cities. University students tend to be the children of the highly educated – they’re in turn more likely to gain higher education. This perpetuates the concentration of the highly skilled.

The slightly better news is that because cities tend to be ethnically mixed, the growing urban bias does not seem to have resulted in a sharp increase in ethnic inequality in university education. In three countries (Ghana, Malawi and Uganda) the censuses also asked respondents to state their ethnicity. Using these self-reported ethnicities, I measured ethnic inequality by cohort. I found much less inequality growth on an ethnic compared to a regional basis.

Since migration is a major driver of this regional differentiation, this trend will probably continue unless there’s more economic development and more job creation outside the main urban centres. This implies that the face of Africa’s educational high-achievers is changing. From a slim educational elite of the 1970s, where most university-educated people had rural or small-town roots, the highest educated ranks are increasingly dominated by people born and raised in the main, multi-ethnic urban centres.![]()

Rebecca Simson, Research Fellow in Economic History, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.