China experienced a massive economic boom in the 1990s and 2000s which increased its demand for resource imports, like oil, from Africa. This led to a model of development finance in which China funded infrastructure in African countries in return for access to resources. This approach became known as the Angola model, because it all started with an infrastructure-for-petroleum partnership between China and Angola in 2004.

Within a decade, however, a shift in China’s approach was needed, for a couple of reasons.

First, African countries are vulnerable to shocks and they struggle to keep up with mounting debt repayments. For instance, in Angola’s case, the price of oil fell from a high of US$115 to below US$50 in mid-2014. More recently, the impact of COVID’s economic shutdowns and supply shocks around the war on Ukraine are taking a toll.

Second, China’s domestic needs are changing. In recent years, climate change and changing diets have put pressure on China’s domestic supply of food. This triggered interest in partnerships that could help. China is also moving away from being an exporter of heavy-industry and energy-intensive manufactured goods. Its focus is more on growth areas, such as higher value-added agriculture and manufacturing. Geopolitically, it also wants to support African development and its own food security.

My study of these shifts reveals a changing relationship between China and Africa, moving beyond a focus on mainly oil and extractive commodities. The new focus is more on industrial production, job creation, investments that lead to African exports, and productivity-enhancing agricultural and digital technology opportunities.

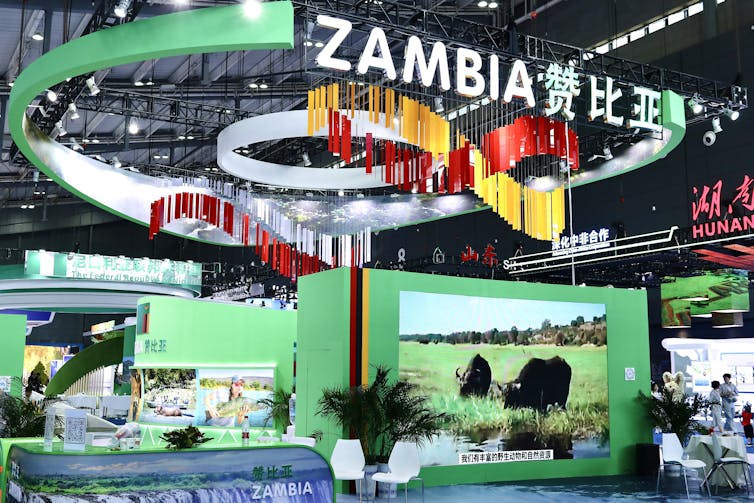

This model, called the “Hunan model”, is named after the province in southern China that is leading the push. African bureaucrats, researchers, trade associations and businesses should understand what’s happening in Hunan. It’ll help them to grasp new opportunities and ensure that African companies are competitively placed.

What is the ‘Hunan model’?

The Hunan model aims to support the 2035 Vision for China–Africa Cooperation by pushing for:

medical cooperation

poverty reduction and agricultural development

trade

investment

digital innovation

green development

capacity building

cultural and people-to-people exchange

peace and security.

The delivery of those goals happens under the umbrella of the China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo and a pilot zone for in-depth China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation. Both are centred on Changsha, the capital of Hunan province.

Hunan province was chosen as the new frontier of China-Africa relations partly because many of China’s competitive industries are based there. They include major agri-tech companies, a leading Chinese electronic vehicle company (BYD Changsha), and manufacturing equipment and construction industry companies. Many of these companies have a presence in, and long-run strategy for, African markets.

China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo

The China-Africa Economic and Trade Expo has many activities and events hosted in big exhibition centres. This allows new business partnerships to be forged with speed and logistical ease. At a 2023 event with 10,000 Chinese and 1,700 foreign participants, it was reported that 120 projects, worth a total of US$10.3 billion, were signed. All 53 African countries with which China has diplomatic relations were present.

Pilot zone

The pilot zone for in-depth China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation is a huge area that’s been developed with the aim of expanding bilateral trade, dealing with bottlenecks in trade and cooperation and improving logistics between the two regions. Examples of typical bottlenecks include market access, finance, logistics, talent and services such as marketing and law.

Some of the initiatives that can be found in the pilot zone include vocational and education training and a digital services hub that supports Chinese companies in the efforts to economically engage Africa. The zone includes a permanent exhibition platform and a demonstration park.

Some implications of the shift

The Hunan model’s specific focus is on agriculture, heavy industry equipment, and transport such as electric automobiles and trains. These are areas where Hunan is a leader within China. And they are growth industries in many countries in Africa.

For China it may lead to new sources of food security as well as new markets for technology products and opportunities to set technology standards. The approach thus places Africa in an important position for grasping new opportunities and shaping related areas of cooperation – at home, with China and globally.

The Hunan model also seeks to support more efficient trade. New trade passageways by rail, river, air and ocean are being forged to better connect Hunan with African countries, especially trade hubs.

There are also efforts to tackle issues of access to foreign exchange and foster greater use of local currencies. At the moment a lot of international trade is done in the US dollar, because it is widely accepted across all countries. But many developing countries struggle to accumulate dollars if they don’t have a commodity like oil or gas to export. Small and medium-sized (SME) traders struggle in particular, and are less able to bear any currency risks against the value of their own local currency. The zone in Hunan includes a centre that is testing trade payment systems based on other currencies. This could become a broader model for SME-based trade in local currencies.

Ultimately, China’s Hunan agenda will mean different things for different African countries and will evolve over time. It’s a recent shift, since 2018 especially, but beyond its potential to elevate food security and production capacity in China and African countries, there will be other important implications. It may facilitate digital and communications logistics for trade between China and Africa, as well as research on technology, industry and trade standards, and trade flows and trends.![]()

Lauren Johnston, Senior Researcher, South African Institute of International Affairs and Associate Professor at the China Studies Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.