Unless you’re heedless, greedy or desperate to ‘escape’ from Nigeria at all costs, there is absolutely no reason to get lured into landlocked Burkina Faso, locked in hell and unable or ashamed to either return to Nigeria or journey further forwards. The offer is too scintillating to be true, the red flags too numerous to overlook.

There is the ridiculous promise of a job offer with dollar earnings — $225 weekly initially, $450 weekly post-probation — but nothing is known about the job description. There is the smooth talk of “a company into gold, watches, jewelleries, necklaces productions [sic]”, but the name of this supposedly gigantic company is never mentioned. There is no job advert, no CV submission (albeit the peddlers pretend to indeed want one), no application portal. The only requirements are a sum of N1.1 million, an identity card, ideally an international passport but possibly the National identity Card.

I forged both, anyway, using my about-to-be-rested pseudonym Paul Runsewe. I knew quite early it was all a ruse: no job with the potential to pay N540,000 weekly, amounting to N2.16 million monthly (as of December 2023), would come that cheaply. But I knew too why many would fall for it: 37% of Nigerians live below the poverty line, according to the World Food Programme, with 4.4 million people being food-insecure in northeast Nigeria.

The victim who initiated the distress call to me in February 2023 was too mortified to even reveal his identity to me. To force his way into Burkina Faso, he had auctioned away his family inheritance, a piece of land handed down to him and his only sibling by their late father. When he reached out the first time, he told me it would also be his last. But before disappearing, he made me make a promise: to someday make my way to Burkina Faso and cover this scam in such a manner as to trigger the governments of Nigeria and Burkina Faso to cripple the operations of the trafficking syndicate. I told him I was uninterested in the story, but I knew I was. I have seen some strange things in my nearly two decades in journalism, but a source appearing and vanishing the same day, leaving no traces at all, is novel, never mind that he had provided me with enough information to stir something in me.

Over the next five months, I ‘found someone who knew someone who knew someone’ who linked me to Olanrewaju, another Nigerian who had fallen for the multi-dollar Burkina Faso job scam but had plotted his way back to Nigeria, his tail between his legs. He lied that he was still in Burkina Faso, chatting with me multiple times on WhatsApp with his Burkinabe line. The truth could no longer be hidden when I finally spent 11 days in Burkina Faso without the faintest sight of him. All of Olanrewaju’s initial conversations with me served to ascertain my seriousness. Once he became convinced of my determination, maybe desperation, to pocket $450 weekly, he handed me over to the self-christened ‘Anointed Femi’, a duplicitous fellow who veiled himself from his would-be victims by sporadically spraying them God’s blessings in his chats.

‘GOD BLESS YOU, MR. PAUL’

Anointed Femi, phone number +22656374175, and I started speaking on WhatsApp on December 5. Two weeks later, on Monday December 18, I left Lagos, destined for Burkina Faso, without knowing how to get there. “From Ojota alight at Mile 2 then call or chats me up [sic]” was all the instruction I had from him, save the occasional “God bless you, Mr. Paul” or “God almighty is your strength”.

It wasn’t until hours before the trip that he started to volunteer more information, again in typically atrocious English:

Happy Sunday Mr. Paul. As discussed you will leave the house very early tomorrow morning reasons are: firstly because of traffic and secondly because of limited Seme bus at Mile 2.

Although STM bus in Cotonou do leave the terminal by 5-6pm on that evening but you need to book on time [sic]. @ Seme boarder buy two big loafs of Nigeria bread and a paint of garri. When you get to Togo/Burkina Faso boarder buy Orange sim card… register it and use it to call I and the person that chatted you yesterday night [sic], why I directed you to do so is because immediately you are out of Seme, on your way to Coutoun… Nigeria sim will ceased you work.

By “the person that chatted you up,” Femi was referring to an unnamed fellow whom he had labelled the “protocol officer”. The protocol officer, phone number +22605079200 and marked Elisha Ayo M on WhatsApp, reached out two days before the trip with nothing of particular importance to say. However, by Monday he had sent me the +22966671569 phone number of Patrice Agbegbe, in whose hands I was to land in Seme, a Nigerian settlement bordering the Republic of Benin.

This trafficking ring was a well-oiled network, with members positioned in strategic locations in Nigeria, Benin Republic, Togo and Burkina Faso. Patrice’s task was to cross me over from Nigeria into Benin Republic. On the surface, it seemed straightforward; it was a motorcycle ride of no more than 10 minutes. But nobody of inexperience or familiarity with border officials could pull it off. Patrice paid N1,500 at the first Nigeria Immigrations security post and N500 at the next.

After moving me past the Seme border into Benin Republic, he rode me to a stall where I changed naira to CFA, shockingly discovering the worth of a naira to be half-CFA, meaning N100,000 only fetched me 50,000 CFA. Then he led me to a stall where I bought a loaf of bread for N1,200, a bottle of water for N800 and two Titus sardine cans for N2,000. Patrice also facilitated, although dubiously, my commute from Seme border to Seme roundabout and then to the STM transport park, where I paid 37,000 CFA to purchase a Burkina Faso ticket and another 2,000 CFA to reserve space for my luggage filled with personal effects I was prepared to lose if it came to that: one pair of jeans, three T-shirts, one polo shirt, toothbrush and paste, a bottle of perfume, body lotion and undergarments. Other than the pair of shoes I was spotting, I had no other in my bag.

Patrice had emerged from the payment counter asking me to “bring the 40000 CFA (N80,000)” without exactly stating the use it was for. He had also demanded 3,000 CFA to clear my luggage even though the attendant would later mention 2000 CFA when I personally inquired. And I believe the 2000 CFA I finally paid was still a rip-off to be shared by the duo, considering it was never receipted. Before all that, Patrice’s personal pay for crossing me through the border should have been N3,000, judging by messages I belatedly saw from the ‘protocol officer’. But Patrice had already fleeced me of N4,000 by then. He demanded 5,000 CFA to get me to the STM park, but he did not get me there himself, only declaring that his motorcycle was faulty after he had collected the cash from me. Instead, Patrice got us on two bikes after deliberately haggling the prices in vernacular even though both riders understood English like me; and he never disclosed the fares. Nevertheless, as I stood in the queue to board the STM bus to Burkina Faso, Patrice had the nerves to request “something for your guy, something from your mind”. I flashed him a curt, wry Lagos smile without muttering a word.

BENIN REPUBLIC TO TOGO

The STM bus departed from the park at 7:00pm prompt — not at “5 to 6pm” as tenaciously advertised by the protocol officer. By 10:17pm we had arrived at the Togo border, an announcer encouraging us to disembark from the bus and file into the Togolese Immigration office to present our passports. Some young men in mufti were soon milling around three passengers, including me, asking us to give up 1,000 CFA for them to take in our passports for stamping on our behalf. It seemed strange to me, so I recoiled, even though the other other passengers were on the cusp of paying. And they would have, had I not been hesitant, and had a gun-wielding officer not emerged to scare them away. The two passengers were effusive in their thanks to me, but I counted it as nothing; I did not live my adolescence in Lagos only to be fleeced by Togolese touts!

IN TOGO, YOU MUST PAY BRIBES WHETHER YOU STAMP YOUR PASSPORT OR NOT

We subsequently formed a queue in front of two young men who were to screen us before sending us to the Immigration desk.

“Show us your passport and Yellow Fever cards!” the darker one ordered. “If you do not have the Yellow Fever card, you pay 5,000 CFA (that is N10,000) to get it here. If you do not want the card at all, you pay only 500 CFA.”

I did have the card, but in my real name. I opted not to procure a second, so I paid 500 CFA and got moved on to the Immigration desk. There, I intentionally asked again what the options were.

“If you do not want your international passport stamped, you pay 2,000 CFA (that is N4,000). if you want it stamped, it’s 4,000 CFA (N8,000),” a rotund, wide-eyed female official told me.

“Thank you, madam,” I replied. “But what is the repercussion for not stamping my passport?”

There was none, she explained; it was all a matter of choice. So I opted not to stamp and pay the required 2,000 CFA. What’s the use of a stamp, anyway, when it isn’t my real passport?

I then walked some 700 metres from that desk to the exit where our bus was scheduled to rejoin us. Four other Nigerians behind me in the Immigration queue recognised me from inside the bus, so we literally huddled together pending the arrival of the bus. They were young guys, all ostensibly under 30.

“Where did you come in from?” one asked another. I could almost tell where the questioner was from. His accent was thick, his skin bleached into irritating fairness.

“I came in from Akure,” he said, after the other young man had answered that he was from Port Harcourt. Aha! ‘The Port Harcourt guy’, by the way, looked the smartest of the quartet by a mile. While the other trio appeared unschooled, he possessed the persona of someone who had tasted higher education.

“I am from Kogi,” the third answered. “If not for the poverty and hopelessness in Nigeria, what would I be doing on this bus?”

The conversation got interrupted by the honks of our bus, and we soon climbed in to continue the journey. At exactly 12:22am, we arrived at the ST\M office in Lome to pick up more passengers.

NIGERIAN IMMIGRATION IS CORRUPT, BUT FRANCOPHONE ONES ARE FANTASTICALLY CORRUPT!

As we approached Togo’s border with Burkina Faso, we were stopped by Togolese Immigration officials who screened us in exchange for 2,000 CFA (N4,000) each. It was a similar experience once we stepped into Burkinabe territory: the same 2,000 CFA. The next two checkpoints extorted 1,000 CFA and 2,000 CFA from us, meaning that three Burkinabe Immigration or Police checkpoints all spaced within 10km of one another fleeced us of a total of 5,000 CFA (N10,000) just to be granted passage. At the fourth checkpoint, in Cupela, we also paid 1,000 CFA.

At the next checkpoint, we filed out of the bus as usual to an Immigration officer on the expressway who screened our IDs and waved us to his colleague standing some 70 metres away. Here, 2,000 CFA was demanded from each of us. We had arrived here at 4:35am, so it was pretty dark. The driver had also picked up more dark-complexioned passengers at the STM park in Ouagadougou. Egged on by a combination of the dark skin colours, the darkness of the late hours, and how we huddled around this second officer rather than queue before him, I turned back towards my bus without paying just as I noticed one of the new passengers had paid and turned. An elderly passenger noticed me and repeated the trick when another old passenger paid. If security men were going to rob me of my hard-earned money, it was my job to fashion out an escape!

I could not pull the trick off at the checkpoint leading to Bobo Dioulasso, though. The driver of our bus himself was the one appointed by the officers to number us and produce the total cash in multiples of 1,000 CFA.

‘BOBO’ IN BOBO DIOULASSO

We arrived at the STM park in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, on Wednesday at about 6:50am Burkinabe time to great relief. It had been three days on the road nonstop, and the toll had become full-blown. I was flustered, dusty and cold, my lips already blistering and my nose starting to redden. My body was quaking and hungering for a warm bath. Femi received news of my arrival with warmth, writing: “Alright I am on my way to receive you. Just stay calm and talk less.” That was the moment I established the true reason for his “talk less” admonition.

When I left Seme for the STM park in Cotonou, Femi had similarly warned me against cultivating friendships on the bus. “Be careful with people you mingle with inside the bus, you understand,” he told me in a WhatsApp voice note. “Most of the people are drug traffickers, you understand. Just be careful. Stay on your own and stay focused; you will get to Burkina Faso.”

At that time, the advice felt strange — what they call ‘bobo’ in Yoruba street lingo. How do you tell an adult whom to mingle with and not? How can most — not some, but most — of travellers be drug traffickers? It looked improbable, but I restrained myself from reaching any hurried conclusions. Asking me not to interact with anyone at the park was the crescendo; I became certain it was a ploy to prevent me from disclosing my mission to anyone capable of setting me free, knowing the invalidity of this supposed multi-thousand-dollar-paying job.

I retrieved my luggage from the trunk of the luxury bus and picked a spot on the median of the first of three wooden benches at the park. I had barely settled into the chair when I felt the pangs of the accidental weight of someone’s leg on mine. It was the Port Harcourt guy!

“Man, I didn’t know we were both coming to Bobo Dioulasso,” I said, paying loose attention to his profuse apology. “Why are you here?”

“Work,” he replied. “And you?”

“Business.”

“What kind of work?” I asked him. He spoke for close to a minute without really saying anything. It was a job. He had interviewed for the role over the Internet. He would earn better than the average Nigerian. But he withheld the specifics, such as name of employer, job designation and pay range.

“Will you be paid in dollars?” I probed further, hoping to establish if we had been recruited for the same venture. He denied, although he mentioned some mouthwatering hundreds of thousands of naira.

“Well, I will be paid in dollars — $225 weekly at the start and $450 weekly later,” I announced unceremoniously, hoping it inveigles him into becoming more comfortable with me. It did not. In fact, he seemed disinterested in the conversation.

“Will you be working for a company that deals in gold, watches, jewelleries and necklaces?”

His answer was a perfunctory “no”, so I figured he had also been warned to “stay calm and talk less”. I let him be, but not without sticking an I-will-definitely-see-you-later parting shot into his face.

Independent, public-interest journalism has never been more vital than in times like this when truth is constantly being suppressed. With your support, it will be easier for us to continue speaking truth to power and preserving your right to know

Make a donation to FIJ today

Donate Now

FROM GOLD TO DUST

There was nothing about the streets of Bobo Dioulasso to suggest the presence of a company with the financial clout to shell out several hundreds of thousands weekly to the thousands of expectant Nigerians in Burkina Faso. Many of the roads were untarred, dusty and bumpy. Most of the taxis plying the city were ramshackle and dingy. There were all sorts of strange moveable engines conveying people around, not least one that felt like an expanded tricycle conjoined to a motorcycle. The air was hot, dry and unfriendly.

Anointed Femi took forever to come and shortly after he did, we hopped into a rickety taxi and headed to an undisclosed location, a drive of roughly half-an-hour . Once we veered off the main road, we were let into one of several streets with clusters of houses without landmarks.

Bobo Dioulasso felt like a village rather than a city, nothing close to the elegant city of gold Anointed got me dreaming of. It seemed implausible that this was Burkina Faso’s second largest city by population, the colonial capital in the era when the country was the Republic of Upper Volta.

‘WELCOME, GENTLEMEN OF THE PRESS’ — HAS MY COVER BEEN BLOWN?

“Welcome, gentlemen of the press,” the chisel-chested man at the other end of the nondescript table said as I attempted to recline into the only vacant of three seats opposite him.

Gentlemen of the press? My heart raced a thousand steps in the following three seconds. Had my cover been blown? What could have given me out? Had my disguise failed me for the first time ever?

“Gentlemen of the press, how?” I summoned the courage to retort, stone-faced, shifting my gaze elsewhere in the room as though wondering whom he was referring to.

“No, it’s you,” he replied. “I mean welcome to you.”

Better!

It was my first time in the flat-turned-office of my new multi-thousand-dollar employers. From the outside, it stood out as the only painted edifice among several blocks of scattered, plastered houses, but the picture inside painted a grim story. The entrance was dotted by a half-a-dozen forlorn faces, the first room littered with close to hundred, scrawny, hungry-looking Nigerians, no more than five of whom were girls, listening to nobody in particular, appearing to be jobless, unhappy and lost.

Meandering my way through to the room inwards was straightforward; a number of them easily recognised ‘Anointed Femi’ and made way for him while I trudged on behind. The next room we entered was west of the building, and the smallest, so it naturally contained the least number of people, four in all, no less scrawny than the ones outside but only pretending to be busy when actually idle. Femi instructed me to “wait here”, then returned within a minute to fetch me for the chisel-chested boss.

“We were already discussing some things,” the boss, whose name I hadn’t yet deciphered, said of his interaction with the two ‘prospects’ opposite him. “But I will go over them again.” A ‘prospect, by the way, is someone to whom the job is being marketed.

Over the next hour, he would ramble on and on about Chinese produce and the chain of marketing that ended in their consumption by African end users, the network of companies burgeoning in Malaysia and entrenching their roots in Nigeria, and a series of high-value products that had become indispensable to humans. To the three of us being newly recruited, he passed round a glass object with the unthinkable ability to neutralise a poisoned drink. He called it a Chi Pendant. The lengthy talk was incongruent and lopsided, replete with multiple unrelated scenarios and tales with no real or apparent connection to the job being offered.

MENTAL OSTRACISM BY ‘SIM ACTIVATION’

When Prince, as I later understood his name to be, was done, he invited Anayo, a tall, languid and widely-travelled Nigerian from Ebonyi State, to administer a biometric form to the three of us as the climax of our registration. The form was basic: full name, date of birth, Nigerian phone number, email address. All through Prince’s remarkably dour speech, three men stood behind us, watching our every move. When we started filling the forms, they edged closer. The last phase of registration was what they called ‘sim activation’. Anayo told us to extract our Burkina Faso sims from our phones and hand them over to him. I found the directive strange.

“My sim cannot be removed from my phone,” I protested. “I don’t have the pin to unhook the sim insertion port.”

“I have it,” Stanley, the thinly-built man behind me, interjected. And before I could turn round, he was already producing it. With it, Anayo retrieved my sim and took possession of it, rolling it into a paper on which he wrote my name, plus the inscription ‘sim activation’.

I kicked. “Removing my sim for activation? Nowhere in the world is that standard practice. You have my number already; it’s enough for any ‘activation’. Nobody needs to actually remove my sim.”

My protestations fell on deaf ears. Anayo tucked my sim away in his paper, anyway, neatly wrapped, and eased his attention to the next recruit. I instantly told myself I needed to discreetly purchase another sim. Therefore, I pocketed Stanley’s pin. Without it, I would be unable to insert the new sim into my phone.

They started to look for it but I denied having it. All seven of us in the room spent some five minutes scouring the room for that pin, but I wouldn’t release it. By then, I had also begun wondering what they would do with my seized sim. Were they going to bug it? Would they hack into my WhatsApp to see whom I had been communicating with. With my Nigerian number, I quickly texted the three people I’d communicated with to clear our chats on my Burkinabe line and ignore any call or text from me.

Then I heaped pressure on Femi: “As long as my sim is with them, your phone hotspot will serve as my Internet.” Knowing the priceyness of Internet access in Burkina Faso, I expected him to press for the swift return of my sim in his own interest. It worked. Femi mounted pressure on Anayo and my sim was returned after five hours. The other two guys, though, had to wait nearly a week to have theirs back.

As I would later find out from other trafficked Nigerians, the sim collection was to deliberately create a communication blockade from the outside world. They didn’t want us to relay our daily experiences to anyone back home, fearing we would be discouraged from proceeding with the process. I could not establish if there was any privacy breach on the line, but I abandoned communicating with anyone on that line altogether.

THE HARD LIFE IN STANLEY’S LODGE

At Stanley’s Lodge, the house Anointed Femi hurled me into, 15 of us occupied a two-bedroom apartment. The thought of sharing a kiosk-size bathroom with 14 flatmates scared me stiff, but I soon understood I was ‘this lucky’ only because I arrived at an off-peak period of the year: December. Normally, in the over 30 lodges in Bobo Dioulasso and Ventura brimming with hordes of fortune-seeking Nigerians, 30 people typically slept in a two-bedroom flat. Someone who left Burkina Faso in March 2023 told me he was “sick and almost dying” from the overcrowded flats.

I could easily relate with his ill-health. In my 15-man flat, five of us slept in each room, the last five occupying what should have been the sitting room. There were only six mattresses at the rate of two per room. This meant one of two things: that two men slept on a mattress while the other three slept on the bare floor, rendering them susceptible to pneumonia; or all five distributed themselves over two mattresses, leading to the cross-exchange of inhaled and exhaled air. And all this was luxury; the last 30-man set to stay in this house included two ladies. How the duo managed to share two rooms and a parlour with 28 men remains a mystery.

The feeding was sickening. Food, served twice daily, was always a certain meal in the morning, repeated in the evening. When it was rice, it came with bland soup made from semi-ripe pepper; and it was topped with fish the size of a baby’s fingers. When it was beans, it arrived watery and yellowish, crying for pepper and palm oil. I gobbled the rice on my first day because I needed to play along, to ensure nobody grew uncomfortable with my presence. But extending that nicety by a further day by eating the beans sent me tumbling in the toilet. It was the first and last time I neared the plate of beans, but it was too little too late: I was the toilet’s guest for an additional six times over the following two days!

It would take me a further three days to know, but all these were in fact honeymoon-phase luxuries. The midget-size fish garnishing my rice was a gesture scheduled to last only the first week, to be excised from the start of the second. The uninterrupted electricity I enjoyed was merely a two-day welcome package; from Day 3, Stanley, the lodge owner, started to turn off the prepaid metre from 6am until 7pm! I was enraged by the 13-hour outrage, but who was I, a common trafficked person, to complain? Even my half-access to the mat-like mattress was a three-day allowance; from the fourth day, I was told I needed to cough up 10,000 CFA (N20,000) if I wanted a mattress and another 1,000 CFA if I desired a bedsheet.

PARADIGM SHIFT!

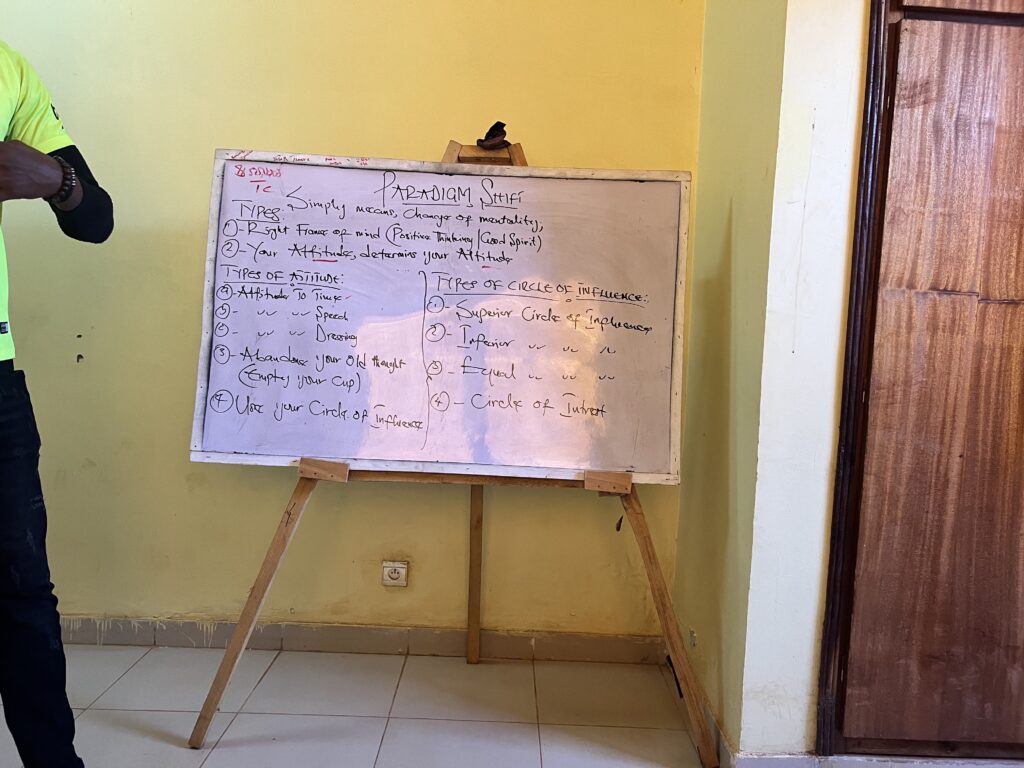

On Thursday December 21, the fourth day of my journey but second in Bobo-Dioulasso, I reported for the next round of training with the other two recruits. The session, typically handled by Anayo, was titled ‘Paradigm Shift’. It was another long-winding session, but Anayo’s presentation was at least more articulate and calculated than his boss’s. With the benefit of hindsight, it was painstakingly prepared to achieve three things: get the victim hooked on patience, believing the dollars would eventually come even if it took forever; motivate the victim to pass on their most immediate and important contacts to the traffickers; and, finally, get the victim intoxicated with huge dollar numbers to the extent that they could do almost anything for this imaginary windfall.

To achieve the first, Anayo sermonised about having the right frame of mind, abandoning old thoughts, and embracing the right attitude to time, speed and personal grooming. It was the classic your-attitude-determines-your-altitude pretentious talk. To achieve the second, he highlighted every individual’s possession of four circles of influence — superior circle, inferior circle, equal circle, and circle of interest — that must either contribute to this dollar course or get discarded. And for the third, he drew a diagram on the whiteboard marker representing potential earnings of the phoney company’s employees during an incredulous 90-year-long contract. He also made us multiply $250 by four weeks, then by one year, and finally by 90, after which he made us convert the earnings to dollars. At the then exchange rate, our monthly earnings amounted to N4.8 million or — if you like — N57.6 million annually and N5.184 billion at the end of the 90 years, never mind that none of us in the room could guarantee living for the next half of 90 years! The current average life expectancy for Nigeria in 2024 is 54.1067 years of age, and nobody in that room was under 20.

To bring the session to a close, he gave all three of us an assignment: to pen the names and contact details of 150 people from Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and our personal lives whom we could ‘prospect’ to Burkina Faso! These 150 were those in the much-vaunted circles of influence. In clearer terms, each trafficked person was being encouraged to become a trafficker!

TOO MUCH AT STAKE

The ensnarement to traffic more Nigerians into Burkina Faso is one that few trafficked persons can extricate themselves from. Nearly every Nigerian currently in Bobo-Dioulasso courtesy of the fake job promise has a story of immense personal loss to tell. My anonymous whistleblower had managed to unwittingly fritter his inheritance away, believing it was a worthy sacrifice for a multi-thousand-dollar-monthly job in Burkina Faso. In my lodge, there was ‘Mr. Dayo’, a sexagenarian from Osun State whose lush dark colour was nicely embellished by his delicately-trimmed white moustache. Before jettisoning his former life in Ilesha for the uncertainty of Bobo-Dioulasso, he had sold his car to raise approximately N1.1 million in travel and job-securing funds. “My money and my car cannot go to waste,” he told me, unaware he was talking to an undercover journalist. “So, my stay in Burkina Faso must work. I’ll give it whatever it’d take.”

Then there was Leke, a young, soft-spoken, likeable, ostensibly under-30 man from Akure who gave up his job at Bet9ja and sourced extra funds from friends and family to make it to Burkina Faso. Leke arrived in Bobo-Dioulasso some two months before me but was determined to stay back until he had brought at least two Nigerians in. “I cannot just return to Akure like that with nothing to show for my journey,” he murmured.

Outside my lodge, there was Akin, a mid-aged father of two who threw away his Bolt riding livelihood, selling his car at a giveaway price to raise travel funds despite the repeated protestations of his wife. Now stuck in Bobo-Dioulasso for three months without having touched a single dollar, Akin cannot bring himself to tell his wife she was right and he was wrong, much less disclosing to her that they must now rebuild their life from scratch. He cannot even contemplate the mortification of an empty-handed return to Nigeria. Akin is still scheming to bring two Nigerian replacements for himself, a quest that has thus far been unsuccessful.

‘CE QUOI AS A BUSINESS. ALONZO!’

On Friday December 22, I was promoted to the general class for the first time. The room was filled to the brim, and there were more participants on the doorway and the courtyard. By my estimation, there were roughly 150 of us. Networker Ajala from Ekiti State, a middle-aged man with a protruding belly and a distinct Ilu-Oke accent, was addressing the audience when I stepped in at about 9:30am.

He encouraged the audience to maximise their Burkina Faso stay by labouring hard for themselves, their loved ones and “the people whose destinies are attached” to theirs. He had his listeners where he wanted them by occasionally adding, “may God help us in Jesus name”, to which they heartily responded, “amen”. At other times, he punctuated his exhortation with “ce quoi as a business”, to which the audience chanted “Alonzo!” Once he even told them: “You are here in Burkina Faso to learn how to shout Hallelujah forever, because Hallelujah is a unique language”.

He ended his talk with a lengthy prayer session during which he willed the destructive fire of God upon “witches and wizards, or powers in your father’s house or mother’s house gathered against your upliftment and prosperity”.

The next speaker was much like Ajala. Although he motivated the dollar-seeking Nigerians for only a third the duration of Ajala’s session, he was more blatant, dedicating some 95 percent of his time to praise, worship and prayers. He did not only pray for his audience, he made them pray for themselves — “against every satanic manipulation” against their business. These satanic manipulations, he fervently prayed, were to “catch fire”. To disperse the crowd of ‘employees’ for the day, he joined them in “sharing the grace”.

FENCED OUT OF CLASSES

My secret filming device failed me during Prince’s opening-day presentation on Wednesday. I hoped to get a second opportunity but it never came. By Friday afternoon, fearing the prospect of leaving Bobo Dioulasso without capturing the most senior member of that office, I demanded to see him, insisting I had questions he alone could answer. His boys obstructed the passageway by his door but my resistance triggered a shouting match that attracted Prince.

When Prince eventually joined me, I asked him basic questions designed to serve no other purpose than getting him on the record. It worked.

I left the class with the knowledge that we were to regroup the following day, Saturday December 23. I was therefore taken aback on Saturday morning when Anointed told me classes had been cancelled, only for me to discover hours later that they indeed held. It became clear my insistence on retaining my sim on Wednesday and my defiance in questioning Prince had betrayed my scepticism of the project; they felt it was best to fence me out of future classes. As Leke would later tell me, it also meant eyes were now on me, and I needed to start hatching my exit from Bobo Dioulasso. But first, I needed to convince ‘Anointed’ that returning to Nigeria would not incapacitate me from ‘prospecting’ for vulnerable Nigerians. He agreed to let me go, provided I furnished him with a ‘hot list’ and a ‘cold list’ — the former containing names of Nigerians who could be persuaded to enter Burkina Faso without fuss, the latter representing those with whom additional time, pressure and manipulation would be required.

ESCAPE FROM BOBO-DIOULASSO

My exit from Bobo-Dioulasso at about 12:30pm on Christmas eve was turbulent. Anointed had led me to the Nour Transport Voyageurs park in Bobo-Dioulasso and my intuition kicked against it, more so after the arrival of a roughly-used bus pungently smelling from the stench of urine, sweat and unbathed bodies. But despite my protestations, Anointed obstinately egged me on. Paying the 35,000 CFA fare proved a horrible decision. The driver ignited the AC as we boarded but switched it off once we took off, leaving us gasping for aeration from the dusty road.

On Christmas Day, at about 12:15am, he pulled up in the middle of nowhere without announcing this was it for the night. The perennial long-distance travellers among us, mostly Nigeriens, took the cue, retrieved their blankets, and settled into deep sleep on our lane of the expressway, much to my disbelief and distress. Inter-country transport services usually have two drivers who alternate to ensure an uninterrupted journey regardless of the duration of the trip. But not Nour.

It was a sleepless night for me. The journey resumed just before dawn, and by the evening of December 25, we had entered Benin Republic territory. But tragedy awaited us. The driver missed his way and started to dangerously overspeed after retracing it, to atone for lost time. The journey became turbulent; he crashed into bumps without caring for the potential damage to the bus, once almost dislocating the television affixed to the roof of the bus. By this point, we had paid bribes ranginging from 5,000 CFA to 4,000 CFA to security officials in Burkina Faso, Togo and Benin Republic at the same points where we did during the first leg of the journey.

At about 7:25 pm in Djougou, some three-hour drive away from Parakou, the largest city in northern Benin, the driver unsurprisingly knocked two bicycles off the road, one rider injuring his right knee while landing in a culvert. Police involvement held us back by five hours and by the time we took off, the driver knew this was no night for him to pull up in the dead of the night for another sleep. At about 3:45 am on December 26, he emptied us in Parakou — not Cotonou — promising a bus would arrive at 6 am to convey us to Cotonou. That did not happen. Instead, we were roused from sleep at 6:27 am by the sudden screeching of two motorcycles stationed at the gateway to take turns ferrying us to Biou Park in Parakou for the seven-hour bus ride to Cotonou. It was a nightmarish trip from start to finish.

The transfer was anything but plain sailing, courtesy of needless penny-pinching by Nour Transport. The riders wanted more money than Nour parted with. Biou Transport, the bus service I settled for, wanted 7,000 CFA but Nour’s offer was a fairly distant 5000 CFA. After endless haggling, we came to a middle ground: we topped Nour’s 5,000 CFA with 1,000 CFA while Biou reluctantly consented to a 6,000 CFA fare. When Biou finally took off, it was not only the final lap of the journey, it was goodbye to any form of bribe paying until we touched Seme, Benin Republic’s border with Nigeria.

CROSSING INTO NIGERIA

Cotonou was our original stop from Biou. From Cotonou, I hired a motorcycle for onward transport to the Seme border, where I easily converted all my CFA to naira. Of note, I had experienced extreme difficulty sourcing naira in Lagos this previous week, meaning that naira, the Nigerian currency, was more available in Benin Republic than in its home country! The bike rider had been honest enough to admit he lacked the powers to cross me from Beninese to Nigerian territory — it was a job reserved for specialists who had forged a reputation for such shady dealings with corrupt border officials — but he would link me to one. At the border manned by Benin Customs officials, my new specialist rider paid 4,000 CFA on my half. He then demanded N10,000 to settle Nigerian Customs and Immigration officials. On each occasion, he pulled over, went in to confer with them and, as I could see from afar, handed them wads of naira notes.

Once we crossed Customs and Immigration at the border, the rest of the journey was easy. The five-passenger cab that conveyed us from the border into the heart of Lagos was driven by a policeman who enjoyed some popularity among the policemen, soldiers, NDLEA, Customs and Immigration officials manning the numerous checkpoints along the route. Some waved him bye once he wound down and they spotted his face; others let him give them of his own freewill. Some others demanded payment of fixed bribes, ranging from N500 to N2,000.

As we scaled the last checkpoint and began approaching the last stretch of the journey leading to Mile 2, I started to marvel at the porosity of Nigeria’s land borders. Here I was crossing into Nigeria all the way from Burkina Faso with a fake travel document with me that nobody spotted. But I had far bigger worries: in faraway Burkina Faso are thousands of Nigerians who, having lost their live savings to the wild goose chase of fake dollar jobs, have become unable or ashamed to return to Nigeria even with their real travel documents.

LIFE AFTER BURKINA FASO

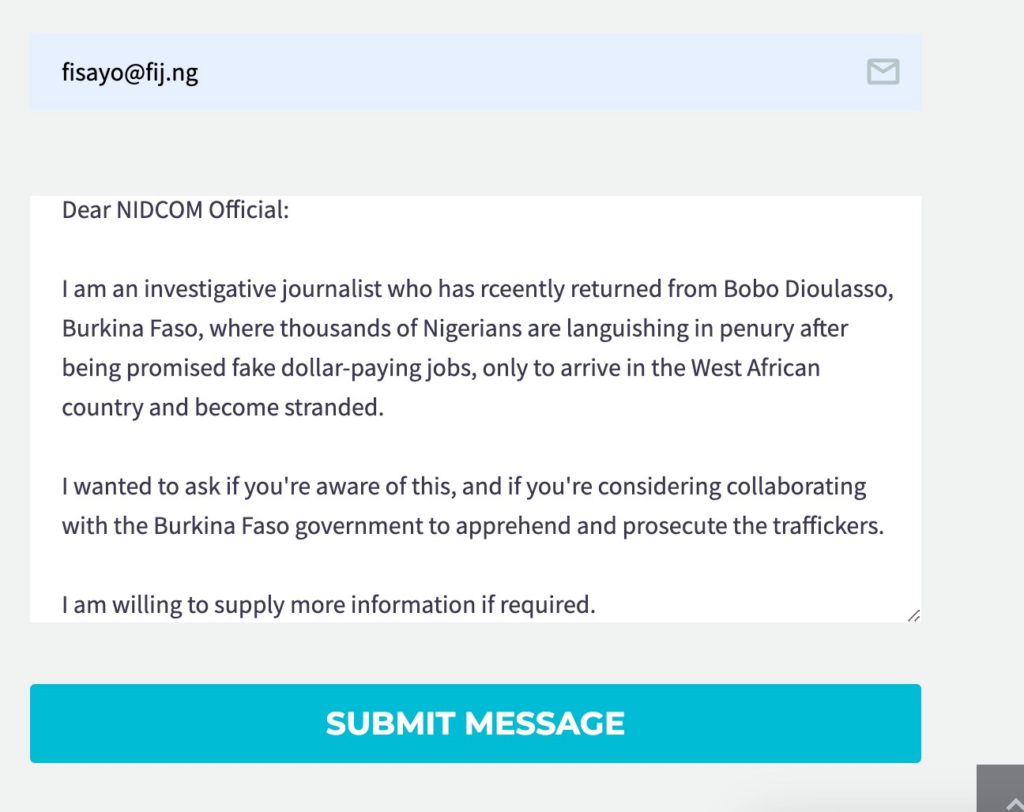

Attempts to notify the Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM), but a feedback form filled on the commission’s website on August 22 has not been responded to as of press time.

Aware of the fraudulent use to which its name was being put, Qnet has since inscribed a bold disclaimer on the homepage of its website.

“We are aware of fake job offers circulating on social media and online forums in the name of QNET,” it states.

“This is not what we do. QNET does NOT offer employment, either domestically or abroad, in exchange for payment.”

Meanwhile, between my return to Nigeria and now, a few things have changed. Some trafficked persons have returned home to Nigeria, having experienced the futility of their mission. They had eventually discovered there were no gold or necklace-making companies in Bobo Dioulasso; just human traffickers operating a ponzi scheme in which humans are the ‘products’.

Some more unsuspecting people have been ‘prospected’ into Bobo Dioulasso. Anointed Femi, unable to lure more Nigerians into Burkina Faso, has now packed his bags and returned to Nigeria. I am told Leke, the man who first warned I had become a source of suspicion, has also returned.

Meanwhile, I returned to Lagos with no job, no dollar – and none of the over N2 million I invested in the trip.

Editor’s Note: A documentary of this investigation will be published on Wednesday, August 28

Independent, public-interest journalism has never been more vital than in times like this when truth is constantly being suppressed. With your support, it will be easier for us to continue speaking truth to power and preserving your right to know

Make a donation to FIJ today

Donate Now

This report was produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation