USA & CANADA (901)

Latest News

US poverty statistics ignore millions of struggling Americans

Monday, 01 July 2019 15:14 Written by theconversation

Sophie Mitra, Fordham University and Debra Brucker, University of New Hampshire

Who counts as poor in the U.S. today?

Measuring the share of the population that experiences poverty is important to understanding and monitoring how the country’s economy is doing. It also informs the administration of safety net programs, such as Medicaid and food stamps.

Poverty is measured in the U.S. in two ways – but both focus on a lack of income. Currently, those who may have some income but lack other key necessities, like health insurance and access to quality education, are invisible in official poverty data.

Other countries, like Colombia and Mexico, as well as international organizations like the United Nations Development Program, are ahead of the U.S. when it comes to considering the many dimensions of poverty.

Measuring by income alone

The first way that the U.S. monitors poverty is through the official poverty measure. This compares a family’s pre-tax income to a threshold. For instance, in 2017, a family of four was considered poor if their pre-tax income fell below about US$26,000.

Using this measure, in 2017, 12.3% of the U.S. population, or 39.7 million people, were in poverty.

The second, newer measure is the Supplemental Poverty Measure. This is an income-based measure that reflects more comprehensively the resources and needs of families, adjusted to geographic differences in housing costs. It adjusts after-tax income by adding resources, such as food stamps, and taking away essential expenditures, such as medical out-of-pocket and childcare expenses.

According to this measure, in 2017, 13.9% of the population, or 44.9 million people, were poor.

However, people who are not deemed “poor” by these measures may still be struggling and disadvantaged in many ways. The experience of poverty is not exclusively about income.

Say a family of four has an income of US$50,000 and two employed adults but does not have health insurance. One child becomes chronically ill, and the family incurs high out-of-pocket medical expenses, defaults on their mortgage and gets evicted from their home.

This family’s sudden multiple deprivations are currently invisible to policymakers, analysts and journalists looking only at income poverty.

Measuring as multiple deprivations

In a April 2016 study, we applied a multidimensional measure of poverty to the U.S.

Using this method, called the Alkire-Foster measure, we looked at five different types of deprivation: income level below the official poverty threshold; poor health; education below a high school level; unemployment for at least the last week; and insecurity due to a lack of health insurance.

We considered individuals or families with two or more deprivations to be poor. Our example family above has at least two deprivations: poor health due to a chronic illness, as well as economic insecurity due lack of health insurance.

Using data from the Current Population Survey, a survey collected by the U.S. Census Bureau, our study found that, in addition to the 40 million Americans who are income-poor, another 5%, or 16 million people, experience at least two deprivations.

Not low-income, but struggling

In May, the U.S. Census Bureau published a report exploring a new multidimensional poverty measure which uses the American Community Survey.

Their measure incorporates more and somewhat different dimensions compared to our study: economic security, education, housing quality, neighborhood quality and standard of living.

Strikingly, like in our study, the Census Bureau study found that about 5% of the population, or 16 million Americans, experienced multidimensional poverty in 2017, but are not income-poor.

In other words, according to both studies, 16 million Americans are struggling, yet they do not show up on poverty monitoring radar screens and may not be eligible for assistance programs.

Trends over time can look different through this multidimensional lens. We found that, from 2013 to 2016, both the income poverty rate and the multidimensional poverty rate decreased significantly. However, in 2017, the decline in multidimensional poverty stalled due to a rise in the share of Americans without health insurance, while income poverty continued to go down, albeit at a slower rate.

Moving forward

While there is no magic bullet for poverty, we feel that it certainly cannot be addressed only through raising wages or increasing the number of jobs.

As the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights noted during his 2017 visit to the U.S., “There are indispensable ingredients for a set of policies designed to eliminate poverty. They include: democratic decision-making, full employment policies, social protection for the vulnerable, a fair and effective justice system, gender and racial equality and respect for human dignity, responsible fiscal policies, and environmental justice.”

A lack of income is not the whole story about poverty. We believe that the Census Bureau and other U.S. organizations that play a role in poverty reduction should adopt a multidimensional measure of poverty, in addition to existing income-based measures. It will provide a comprehensive tool to monitor and address Americans’ disadvantages.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

Sophie Mitra, Professor of Economics, Fordham University and Debra Brucker, Research Associate Professor at Institute on Disability, University of New Hampshire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Strict US Anti-Abortion Laws Forced a Woman to Give Birth to a Baby Without a Skull

Friday, 28 June 2019 00:55 Written by sciencealertModern medicine has allowed humankind more control over life and death than ever before, and yet sometimes, the idea of 'choice' is simply a lie, writes an anonymous US physician.

Whether a lawmaker, a doctor, a nurse or an expectant parent, our hopes, desires, beliefs and choices cannot save those who are doomed.

In these situations "all we can control is our grief", and in some states, this particular doctor argues, we are not allowing pregnant women or the professionals who treat them that ultimate dignity.

Recently published under the title "The Myth of Choice", this doctor's harrowing essay is a vivid reflection on one such experience, when a heavily pregnant woman was forced to give birth to an infant with no skull.

Known as anencephaly, this fatal birth defect affects only 1,206 pregnancies a year in the US, and at the severity this doctor detected - with no brain or skull at all, and only a brain stem - it has absolutely no survivors.

Speaking through an interpreter whose video feed was mounted on a television screen, the doctor had to explain this to the hopeful mother who, due to her circumstances, hadn't had an opportunity to reach a medical facility until that point.

"Her eyes plead with you. End it," the physician recalls. "You talk to the obstetricians, because eventually it will end. But nobody will do it. Not in this state. Not in this hospital. And so, the mother goes home, pregnant and grieving."

A few days later she returns. She is having a miscarriage, and after it is born, the mother cannot bring herself to hold her child. Moments later, the severely deformed infant died.

"Some of the nurses need you to fix it, to save this baby with the magic of medicine," the essay continues.

"You remind them that he is very premature, that he has no brain, that he cannot survive. This is not an ambiguous diagnosis."

With no standard treatment or cure, the hospital staff, who are used to doing everything they can to save a life, understandably feel helpless. Watching them grieve, the doctor recalls all the other women who have had their wishes "warped by politics".

"Dignity in grief is the gift," they conclude. "You've enabled false hopes, not for cures but for time to bond, hope, and heal. It is the parents you are healing. The hopes false. All these children died in the end."

This heart-wrenching, first-person account has been published amid a wave of anti-abortion laws in the US, some of which provide few exceptions, even for incest or rape. In Alabama, for instance, abortions are now only allowed when necessary for the mother's physical health, while her mental health and the health of her infant are rarely considered.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, abortions made in the third trimester are extremely rare, account for less than one percent of all cases, and usually involve fetal anomalies, such as anencephaly, which are deemed "incompatible with life".

While laws on this controversial and politically-loaded decision can vary right across the US, currently 43 states have a ban on certain abortions in late-term pregnancy.

Yet however it might sound to the layman, medically, a "late term" is a pregnancy that extends past the pregnant person's due date.

Meanwhile, political opponents use the phrase "late-term abortion" to describe abortions performed after about 21 weeks of pregnancy. (By the same token, a 'heartbeat bill' has nothing to do with an embryo having a real heartbeat.)

In a recent book on the history of abortion, sociologist Ziad Munson explains that there is nothing natural about how we think about abortion or the role it plays in politics and society.

"Instead," he says, "abortion has been constructed as a controversial issue because of a variety of historical events, the decisions of various individuals, organisations and social movements over the course of the country's history, and the ways in which social environments have changed over time."

The abortion debate is, and always has been, a cultural and social divide, based on disparate approaches to the complex question of the beginning of life.

"The Myth of Choice" may well drive the political wedge even further, and yet it brings up an important point: On certain occasions, saving the unborn life is impossible, and abortion may be the most merciful decision for all those involved.

"You've seen these infants cut, lanced, and battered in the name of intensive care," the anonymous doctor writes.

"Do everything. Because who does not want to save her child? Sometimes all we can control is our grief."

The essay was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ontario public health cuts will endanger the public

Friday, 28 June 2019 00:41 Written by theconversation

Thilina Bandara, University of Saskatchewan

Ontario recently announced that it will reduce funding towards public health agencies across the province to the tune of $200 million.

The Ford government also proposes to reduce the amount of public health units from 35 down to 10 over the next two years.

This has caused an uproar in the province, and generated anger from big-city mayors, concern from local health officials and expressions of public protest — due to the amount of funding being cut and the speed at which these cuts are occurring.

The cuts come as a surprise to many and will create a period of public vulnerability, as officials scramble to reorient around a new fiscal environment.

Read more: Explainer: How we all benefit from the public health system

This is an issue worth careful consideration. Not only is public health essential for a healthy state in general, but we are in a moment in time that requires especially strong public health infrastructure.

Public health averts large-scale disasters

As Toronto’s medical officer of health, Dr. Eileen de Villa explained to the Toronto Star, public health is invisible in its effectiveness. That is because public health personnel are in charge of large-scale issues like environmental hazard mitigation, disease prevention, food safety and health surveillance.

When these health issues are managed correctly, large-scale disasters are averted. Ironically, it’s exactly these merits that make public health a target for cuts.

David Hemenway, professor of health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, suggests that in the United States reductions in public health resources are not only dangerous to society, they are predictable due to the non-personalized, politically unpopular and long-term nature of up-front investment into public health interventions.

In the United Kingdom, public health budgets are also reportedly considered a “politically soft target,” especially after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Cuts to public health in Canada occur in an already resource-strapped environment. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that the public health system represented only 5.5 per cent of total health expenditures in 2017.

This is despite public health being arguably responsible for the largest contingent of patients in the health-care system: everybody.

Public health investment pays for itself

As microbes are becoming resistant to treatment, income inequality increases, the climate shifts, measles re-emerges around the world and substance abuse devastates a generation, public health officials need not only resources, but the confidence to mount meaningful long-term initiatives to protect the public.

And they don’t do it alone. Public health also serves as a connection point for other agencies who must work together to tackle these “wicked” problems.

Read more: Wicked problems and how to solve them

And while public health deals with the threats of today, this activity also reduces future burdens that the province will have to pay for in the form of overcrowded hospitals — an issue the Ford government is specifically looking to remedy.

A systematic review of the cost effectiveness of public health interventions suggests that cuts to public health activities for the sake of cost-saving represent a false economy. This is because public health interventions pay for themselves in future health-care costs at a staggering 14.3:1 ratio.

Findings like these reveal a deep and re-occurring misunderstanding of what constitutes value in health-care spending.

Rife with confusion and instability

It is difficult to articulate the level of discrepancy between the current Ontario administration’s priorities and best practice in public health.

Ceasing funding to some supervised injection sites while loosening public alcohol consumption restrictions is an exemplary case of such a paradox.

The most recent cuts continue this narrative of a new direction for public health infrastructure in Ontario, one that is rife with confusion, restructuring and instability.

A deficient, paranoid public health system may create short-term budget savings, but will create huge problems in the long term.

Thilina Bandara, PhD, Community and Population Health Sciences, University of Saskatchewan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Details of Osinbajo’s meeting with US Vice President, Pence

Thursday, 27 June 2019 23:33 Written by dailypost.ngNigeria’s Vice President, Yemi Osinbajo, SAN, and his American counterpart, Mike Pence, held discussions in the White House, with both leaders affirming the mutual benefit inherent in a deeper bilateral relationship between both countries.

They spoke on economy, military assistance and other issues and affirmed the need for continuous observation of the rule of law, while also noting Nigeria’s pride of place on the African continent and America’s reputed global leadership.

Osinbajo was quoted in a statement by his spokesman, Laolu Akande, as saying that, “The US is a natural ally of Nigeria, as Nigeria and US have many things in common.”

He noted that with Nigeria being the largest economy in Africa, its market offers great opportunities to US investors.

In their discussions on economic matters, Mr. Pence said, “Nigeria is a great country with a population of 200 million people, that’s a great nation. We want to see Nigeria prospering more.”

US VP Pence then told his Nigerian counterpart that, “I am grateful that you reached out, the door is open for more dialogue.”

He said Nigeria should continue to pursue market reforms in the economy and encourage an independent judiciary, adding that the rule of law will contribute to Nigeria’s future.

Both leaders also discussed Nigeria’s economic diversification efforts, during which Prof. Osinbajo spoke on how Nigeria is deepening the manufacturing industry and trying to reform the power sector to allow for more investors.

He appreciated the support of USAID through its Power Africa initiative that is helping Nigeria to further open the space in the power sector.

On the issue of security challenges and military assistance, the Nigerian VP thanked the Trump administration for its support on the purchase order for the Tucano aircrafts, stressing that such military equipment will help the Federal Government in the battle against terrorism and insurgency.

Discussing government’s efforts to secure the release of Leah Sharibu, Prof. Osinbajo expressed the commitment of the Buhari administration to continue to negotiate for her release and that of the remaining abducted Chibok girls.

“Over 100 of the Chibok girls that were abducted even before President Muhammadu Buhari came into government, have been released under the Buhari administration,” the VP explained adding that most of the Chibok girls, 90% of them, were also Christians.

The American VP was said to have appreciated the efforts of the Nigerian government and offered US’ support in ensuring the release of others still abducted.

Mr. Pence said he “appreciates the perspective on Leah Sharibu,” adding that, “I am aware of the sensitive nature of her plight,” while also noting that most of the girls that were released in the Chibok abduction were Christians.

Popular News

Canadian drug mule sentenced in Australia for cocaine cruise

Tuesday, 18 June 2019 05:20 Written by oasesnews

Melina Roberge, left, and Isabelle Lagace. Photo from Instagram.

Melina Roberge, 24, told the New South Wales state District Court that she risked a life sentence in an Australian prison for the opportunity to take selfies “in exotic locations and post them on Instagram to receive ‘likes’ and attention” during a $17,000 vacation she couldn’t afford.

Three Quebecers have pleaded guilty to smuggling 95 kilograms of the drug in suitcases aboard the MS Sea Princess during a seven-week cruise in 2016 from Britain to Ireland, the United States, Bermuda, Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Chile then Australia.

Roberge was sentenced to a non-parole period of 4 years and 9 months in prison before she is likely to be deported to Canada.

Judge Kate Traill condemned Roberge’s motivation for crime as a “very sad indictment” on her age group who “seek to attain such a vacuous existence where how many ‘likes’ they receive are their currency.”

“She was seduced by lifestyle and the opportunity to post glamorous Instagram photos from around the world,” the judge said. “She wanted to be the envy of others. I doubt she is now.”

Roberge’s accomplice with whom she shared a cabin, Isabelle Lagace, 29, was sentenced in November to 7 1/2 years in prison backdated to their arrest. Lagace will also likely be deported after serving a non-parole period of 4 1/2 years.

Police with sniffer dogs found 35 kilograms of cocaine in their cabin on Aug. 28, 2016, when the liner, operated by California-based Princess Cruises, berthed in Sydney.

Lagace told the court she took part to settle a debt in Canada.

Roberge did not admit her guilt until days before her trial was due to begin in February.

Traill said Roberge was recruited by a wealthy Canadian benefactor, whom Roberge described in court as her “sugar daddy” but never identified for fear of repercussions for her family in Canada, with the lure of a free vacation.

The third accomplice, Andre Tamin, 65, will be sentenced in October. He was caught with 60 kilograms of the drug in his cabin.

In an affidavit admitted to the court, Roberge said that at the time she was “a stupid young woman” who was governed by superficial goals.

“I have devastated so many people in the process,” she wrote.

The court heard Roberge met her “sugar daddy” in 2015, and they began an intimate relationship while she worked as an escort for him. He invited her to work as an escort in May 2016 during a trip to Morocco, where he first invited her to join drug-smuggling voyage.

Traill said the then 22-year-old was “there to look pretty,” acting as a decoy to the drug dealing below deck.

Roberge told the court she suspected drugs were brought aboard at Peru, because of increased activity during a stopover there.

The judge said Roberge was also motivated by profit. She was promised the ticket, 4,000 euros (US$5,000) in spending money plus more cash once she returned home.

The U.S. Department of Homelands Security and the Canada Border Services Agency identified the trio as high-risk passengers among the 1,800 on board. The haul was a record for cocaine smuggled in luggage through an Australian air or sea port.

Rod McGuirk, The Associated Press

originally posted at https://ca.news.yahoo.com/canadian-drug-mule-sentenced-australia-094015447.html

A growing source of Canadian asylum-seekers: US citizens whose parents were born elsewhere

Saturday, 15 June 2019 12:15 Written by theconversationSean Rehaag, York University, Canada

Jokes about moving to Canada became common among progressives in the United States during Donald Trump’s presidential bid. When he won, a spike in U.S. citizens seeking information about how to relocate crashed Canada’s immigration website.

I’m a scholar of Canadian immigration law and will soon become the director of the Centre for Refugee Studies at York University in Toronto. My friends and colleagues in the United States, who still make those jokes, are often surprised when I fill them in on how U.S. immigration patterns in Canada have changed during the Trump administration.

Overall, the number of U.S. citizens who have immigrated to Canada for any reason rose from 7,522 in 2015 to 9,100 in 2017. In contrast with this modest 21% increase, the number of U.S. citizens applying for refugee protection during the same two years spiked by more than 1,000%. It grew from 69 in 2015 to as much as 869 in 2017.

The more than 1,500 U.S citizens who have sought a safe haven in Canada are mainly the children of people fearing deportation due to a change of their immigration status after spending years in the United States. Even with the recent increase, they still account for a small share of total applicants for refugee protection in Canada – only 1% in 2018, for example. Nonetheless, the dramatic growth in the number of refugee claims by U.S. citizens illustrates some of the differences between Canadian and U.S. immigration policies.

Long history

People from the U.S. have been seeking asylum in Canada since at least the 18th century.

Fearing mistreatment in the newly established United States, and drawn by offers of free land, as many as 100,000 British Loyalists fled to what is now Canada during and after the American Revolution.

Many enslaved people seeking liberty via the Underground Railroad, prior to the Civil War, headed to Canada. Around 20,000 to 40,000 made lives for themselves there.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some 100,000 young U.S. men, many with wives and children, came to Canada during the Vietnam War to avoid being drafted into military service – or in some cases after deserting. Canada enacted a law that let these “draft dodgers” immigrate with lawful status. Even though President Jimmy Carter issued a blanket pardon for them when he took office, about half remained in Canada.

More recently, dozens of U.S. soldiers who had voluntarily enlisted in the military and served in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan sought asylum in Canada to avoid jail time when they deserted because they came to object to those wars. This time, the Canadian government denied most of their refugee claims, saying that they could have possibly qualified for conscientious objector status back home. However, the Canadian public expressed substantial support for these war resisters.

Change of status

The more recent wave of asylum applicants is related to changes in U.S. immigration policy.

Before Trump took office, the U.S. had granted hundreds of thousands of immigrants without papers from Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti, El Salvador and other countries temporary protected status. These policies protected formerly undocumented immigrants from deportation and let them work legally.

The Trump administration has tried to end temporary protected status for eligible immigrants of many nationalities, despite evidence that many of their countries remained dangerous or their economies were still too unstable for them to return.

For example, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an autonomous agency of the Organization of American States, asserts that Nicaragua operates as “police state” with government-sponsored repression that is resulting in hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries. The UN Refugee Agency estimates that 62,000 Nicaraguans have fled to neighboring countries in the past year.

For now, the fate of about 300,000 of these immigrants from multiple countries awaits resolution in the courts.

A big share of the families with U.S. citizen-children seeking asylum in Canada today are immigrants from Haiti and other countries who fear losing their temporary protected status. Some people with this status from Nicaragua and Honduras have had it since 1999. Qualifying Sudanese immigrants have been shielded from deportation since 1997. The U.S. granted 59,000 Haitians temporary protected status in 2010, following a big earthquake.

Canada will probably deny the refugee claims of the U.S. citizen children because the system requires applicants to prove a well-founded fear of persecution in their country of origin. In this case, that would be the United States rather than, say, Haiti, Sudan or El Salvador.

But parents who obtain refugee protection in Canada will be able to obtain permanent residence for their children as well, putting them on the path to citizenship in Canada. Many likely will succeed with their claims. Canada approved about half of the refugee claims made in 2018 after migrants crossed the U.S. border.

Indeed, some of the families with U.S. citizen children seeking asylum in Canada may figure that they are more likely to succeed in Canada than in the U.S. For example, Canadian refugee law is more permissive than U.S. asylum law for people fleeing gender-based violence or gang violence – both common types of claims for Central American asylum-seekers.

Different policies

Canadian and U.S. immigration policies have always been distinct but the contrast is becoming more stark.

Trump campaigned on an anti-immigrant agenda, while Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised voters he would increase the number of resettled Syrian refugees welcomed in Canada. On the same day that Trump first decreed a Muslim travel ban, Trudeau famously tweeted out his hospitality: “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith.”

Under Trudeau’s leadership, the Canadian government has decided to boost the number of immigrants it grants permanent resident status yearly, from 286,000 in 2017 to 340,00 in 2020.

The U.S., with a population that is nearly nine times bigger than its northern neighbor, grants permanent resident status to 1.1 million newcomers. The Trump administration is trying to overhaul the nation’s immigration policy in ways that could cut that number considerably and it has slashed refugee admissions. In April 2019, Trump addressed the rising number of asylum-seekers arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. “We can’t take you anymore,” he said. “Our country is full.”

As long as these sorts of divergences persist, I believe that immigrants who have been living in the United States for years, some with children who are U.S. citizens, will keep coming to Canada seeking asylum.

Sean Rehaag, Associate Professor, Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Canada must end complicity in China's brutal organ trafficking regime

Saturday, 15 June 2019 12:02 Written by theconversation

Maria Cheung, University of Manitoba

The clock is ticking on Canada’s chance to enact important measures against organ trafficking.

For the past two decades, the Chinese regime has been killing prisoners of conscience for their organs. The purchase and sale of human lives has become an industry, and Canada, among other developed countries, has been supporting it.

Bill S-240 seeks to put a stop to Canadian complicity by criminalizing organ tourism. The bill has received unanimous consent from both the Senate and the House of Commons, and is awaiting final Senate approval before the end of the parliamentary session before it can be passed.

This is a critical moment of decision for Canada.

As a member of the Canadian Committee of the International Coalition To End Transplant Abuse In China, I have been among those advocating for Bill S-240, an act that brings important changes to the Criminal Code and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act in order to combat organ tourism.

Live organs on demand

Organ trafficking is a global phenomenon. However, forced organ harvesting deserves special attention in the context of the Chinese. In China, this practice is driven by the state.

It’s directed at prisoners of conscience to advance policies of genocide. Forced organ harvesting in China is carried out at such scale that it constitutes an industry.

Since the early 2000s, Chinese hospitals have been providing live organs on demand. Perfectly matched organs can be obtained in weeks or even days.

With an estimation of 60,000 to 100,000 major organ transplant cases per year in China, the availability of organs cannot be accounted for by the number of death-row executions and voluntary organ donations.

Falun Gong, Uyghurs, Tibetans targeted

The sudden boom in organ transplantation in China coincides with the start of the eradication campaign against Falun Gong. Since July 1999, Falun Gong practitioners have been incarcerated and tortured in massive numbers. During captivity, Falun Gong adherents have been singled out for organ examinations and blood tests.

As well as the Falun Gong, Uyghurs, Tibetans and some Christian sects are also being targeted. Forced organ harvesting is continuing despite China’s announcement that it’s going to stop the illicit practice.

Human Rights Watch reported in December 2017 that the Chinese government forcibly collected biodata, including DNA and blood samples, from 19 million Uyghurs that year under the guise of a free public health program in which all citizens are given physical examinations.

At the same time, the Chinese regime began mass arrest and incarceration of Uyghurs, with a million Uyghurs imprisoned in concentration camps. Meanwhile, a priority lane labelled as “special passengers/human organs transport lane” appeared in the Kashgar airport of Xinjiang Uyghur.

Canadians travel to China for illicit organs

For the past two decades, Canada, among other developed countries, has been a participant in this abuse. Dr. Jeff Zaltzman, the head of renal transplants at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, revealed in 2014 that he alone had at least 50 patients who had gone to China for transplants. Zaltzman has since advocated for changing legislation to address the issue of forced organ harvesting.

Canada has, in fact, been identified as one of the seven major organ-importing countries, alongside the United States, Australia, Israel, Japan, Oman and Saudi Arabia.

Barring a few exceptions, the Canadian Criminal Code only criminalizes acts committed in Canada. As such, it is currently legal for Canadians to travel abroad and obtain organs from illicit sources, because such acts do not take place on Canadian soil.

An extraterritorial offence

Bill S-240 recognizes the extraterritorial nature of organ transplant abuse. By making the purchase of organs, and obtaining organs without donors’ informed consent an extraterritorial offence, the bill creates important measures to stem the flow of organ tourism to countries such as China.

The proposed legislation would also bring Canada into further conformity with emerging international legal norms, such as the principle against transplant commercialism enshrined in The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.

Countries like Israel, Spain, Taiwan, Italy and Norway have already enacted similar legislation. The European Union and United States have issued a declaration and resolution respectively condemning the crime of forced organ harvesting.

On Dec. 11, 2018, the China Tribunal — an independent people’s tribunal chaired by Sir Geoffrey Nice, former deputy prosecutor who led the prosecution of Slobodan Milosevic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia — stated the following in its interim judgment:

“The Tribunal’s members are all certain — unanimously, and sure beyond reasonable doubt — that in China forced organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience has been practised for a substantial period of time involving a very substantial number of victims.”

The final judgement is due to be released on June 17.

It’s vital that Canada ensures Bill S-240 is passed.

China plans globalization of mass murder

China has further ambitions to develop organ transplantation into an export industry as part of China’s “Belt and Road” initiative.

The industrialization and globalization of organ transplantation is the industrialization and globalization of mass murder. If this practice is allowed to take root in human societies, ever more vulnerable populations would be sacrificed in the pursuit of a healthy life by the powerful and the rich.

The cost of inaction means a continuation of Canadian complicity in one of the worst crimes of our times. It is vital that Canada passes this legislation before the end of this parliamentary session, bringing this complicity to an end.![]()

Maria Cheung, Professor of Social Work, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What the US could learn about vaccination from Nigeria

Tuesday, 11 June 2019 08:48 Written by theconversation

Shobana Shankar, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York)

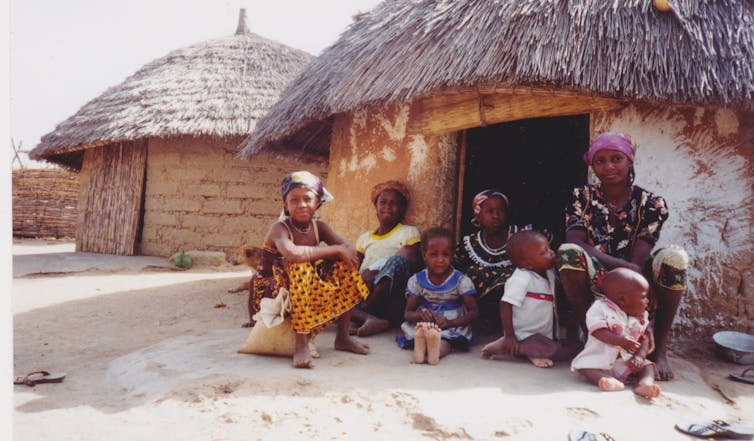

To consider that Nigeria, infamous for anti-vaxx campaigns leading to polio outbreaks, has any lessons for Americans may be shocking.

But as measles cases in the U.S. climb to an all-time high after the disease was declared eliminated in 2000, U.S. public health officials have been looking for ways to address the problem.

As a researcher on religious politics and health, I believe that Nigeria’s highly mobilized efforts to eliminate polio can teach America how to reverse the increase in measles cases and shore up its public health infrastructure. Working with international partners, Nigerians have combated misinformation, suspicion of vaccine science and religion-based boycotts to go from ground zero for polio on the African continent in 2003 to nearly polio-free in 2019.

Comparing Nigeria and the US

When the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was established in 1988 with the goal of complete eradication by 2000, several countries could not meet the target.

India needed another 14 years, while Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan faced stiff internal opposition to immunization. GPEI’s big 2003 push came shortly after Nigeria’s northern states implemented Sharia (Islamic law). Some clerics and political leaders encouraged boycotting immunization, citing contaminants that could reduce the Muslim population and mistrust of the government.

The U.S. is facing similar resistance now. Under scrutiny are anti-vaxx Orthodox and Hasidic Jews in New York City and Rockland County, but The New York Times has also uncovered resistance among Muslims, Catholics, Waldorf school parents and other cultural dissenters.

Anti-vaxxers in Clark County, Washington, are not religious opponents but rather Russian-speaking immigrants who, according to a report, harbor “mistrust of government that built up after being exposed to years of propaganda and oppression in the Soviet Union.” A doctor in their community blames tribalism for suspicion of “people coming from outside.”

Tackling tribalism

Nigerians understood that simply ostracizing religious communities would not work. Anti-vaxx politics tapped into mistrust of government and “others” that ran deep in a diverse but divided society, where religious, regional and ethnic loyalties took priority over national unity.

Nigerians know the ravages of tribalism better than most Americans. By conservative estimates, their nation is home to more than 250 ethnolinguistic groups. The civil war, lasting from 1966 to 1970 after anti-Igbo pogroms in the Hausa-majority north, was a terrifying manifestation of the hatred of difference and a total lack of faith in the government.

To foster reconciliation, Nigerians engaged in efforts to break down tribalism. One experiment, started in 1973 and still going, is compulsory service of college graduates in the National Youth Service Corps in “states other than their own and outside their cultural boundaries to learn the ways of life of other Nigerians.” Notwithstanding problems, the program has instilled in Nigerians a sense that education alone is not enough to build a healthy society. Sometimes it is the source of social separation.

Using this logic to combat polio, Nigerian public health officials took themselves to anti-vaxxers, leaving behind their offices in the city to visit villages with reported polio cases. Their mobility built the “polio infrastructure” that “intensified political and managerial support from all levels of the Nigerian government,” according to a Gates Foundation white paper that analyzed global polio eradication. Traditional leaders like the Sultan of Sokoto also invested time and energy into immunization campaigns and social engagement.

Intensive socialization across class, education and other divisions were as important as traditional public health measures such as scale-up of local technical capabilities and independent monitoring.

Nigerian physicians in the field

I accompanied a team to a village outside Kano city in 2011, after years of public health interventions had reduced reported cases of polio to 20 in all of Nigeria for a 13-month period. The doctor leading the team leader had met four chiefs regularly; the eldest was the most supportive, the youngest the least.

The doctor asked the young man to roll up his left sleeve and pointed to a round scar on his upper arm, remarking, “Your parents had you vaccinated against smallpox. This campaign, though for a different disease, is the same. What’s the problem?” The young chief shrugged, ashamed at direct confrontation and unwilling to insult his parents. They bantered for a bit before we left in the Ministry of Health truck, having accomplished seemingly nothing but a social visit.

“Some may never vaccinate,” the doctor told me, “but I feel better equipped than you or another stranger to talk to them about this issue.”

Between mass immunization campaigns, he visited the villagers. “I know them now, their excuses, habits. Some men say the women are unreasonable. Others don’t care. I know their different personalities. And they know I know them.”

The polio infrastructure in Nigeria immerses experts and local communities in an ongoing relationship. It is an elaborate multilayered surveillance system, with many strategies and functions, from mundane visits to weekly record reviews at health centers in polio-affected areas.

Good strategies matter more than good stories

The media in the West tend to talk about anti-vaxxers as weird and foreign, because they “make a good story,” writes researcher Amanda Vanderslott. She describes common hidden problems like vaccine delays and equipment shortage that sometimes prevent full immunization coverage, but these reasons are less sexy than anti-vaxxers, who are themselves a tribe sharing false beliefs peddled online by discredited doctors like Andrew Wakefield.

Criticism of parents not vaccinating their children may now be commingling with broader mistrust of, say, Facebook. Propaganda and tribal isolation have always existed but now are proliferating with social media that is, paradoxically, fostering anti-social tendencies.

Fearing negative attention would isolate anti-vaxxers and drive them underground, Nigeria fostered greater social engagement in the public health system. The nation’s polio infrastructure was tested in 2017 by new cases in the Lake Chad basin where Boko Haram’s violence reigned. Although international political observers feared the public health effects of Islamist-inspired terrorism, a common element in the remaining polio-affected countries, Nigeria’s disease surveillance capabilities held strong and surpassed those of Pakistan and Afghanistan in its polio surveillance capabilities in 2018.

One clear lesson for the U.S. from Nigeria’s experience with expanding vaccinations is that we should work to depoliticize public health. Scapegoating religious communities evokes ugly histories of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

Tribalism and insularity affect many communities, even the educated and political classes. Nigerians have rarely held back criticism of the elites who blame the masses for their own poverty and illnesses. Ordinary Nigerians, in turn, blame elite corruption for destroying the public sector including public health. Nigeria’s postwar efforts to reduce social stigma and scapegoating are unfinished business, but the polio eradication campaign is continuing the good fight.

Few American college grads will spend years immersed in a social experiment, but public health officials can prioritize resocialization around measles. For America to strengthen its measles infrastructure, trust to discuss and debate vaccine science needs to develop.

GPEI had to rejigger its own understanding of the interactions between monovalent oral polio vaccine and wild polio behavior. Like it or not, American public health officials must answer American advocacy groups like Informed Choice that highlight “the messy conundrum” of exposure to wild measles versus the existing measles-mumps-rubella vaccination strain. A disease infrastructure built on human capacity can handle disagreement.

It can also adapt. Nigeria spent over US$8 million on surveillance alone and expanded polio capabilities to fight other diseases like measles and rubella. While the system puts a heavy workload on health officials, it points the way for how the American public health system can reshape existing structures for the current era. America led international health partnerships for decades, but the time has come to follow other countries’ lead.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Shobana Shankar, Associate Professor, History/Africana Studies, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.