USA & CANADA (901)

Latest News

QAnon and the storm of the U.S. Capitol: The offline effect of online conspiracy theories

Thursday, 07 January 2021 13:08 Written by theconversation

Marc-André Argentino, Concordia University

What is the cost of propaganda, misinformation and conspiracy theories? Democracy and public safety, to name just two things. The United States has received a stark lesson on how online propaganda and misinformation have an offline impact.

For weeks, Donald Trump has falsely claimed the November presidential election was rigged and that’s why he wasn’t re-elected. The president’s words have mirrored and fed conspriacy theories spred by followers of the QAnon movement.

While conspiracy theorists are often dismissed as “crazy people on social media,” QAnon adherents were among the individuals at the front line of the storming of Capitol Hill.

QAnon is a decentralized, ideologically motivated and violent extemist movement rooted in an unfounded conspiracy theory that a global “Deep State” cabal of satanic pedophile elites is responsible for all the evil in the world. Adherents of QAnon also believe that this same cabal is seeking to bring down Trump, whom they see as the world’s only hope in defeating it.

The evolution of QAnon

Though it started as a series of conspiracy theories and false predictions, over the past three years QAnon has evolved into an extremist religio-political ideology.

I’ve been studying the movement for more than two years. QAnon is what I call a hyper-real religion. QAnon takes popular cultural artifacts and integrates them into an ideological framework.

QAnon has been a security threat in the making for the past three years.

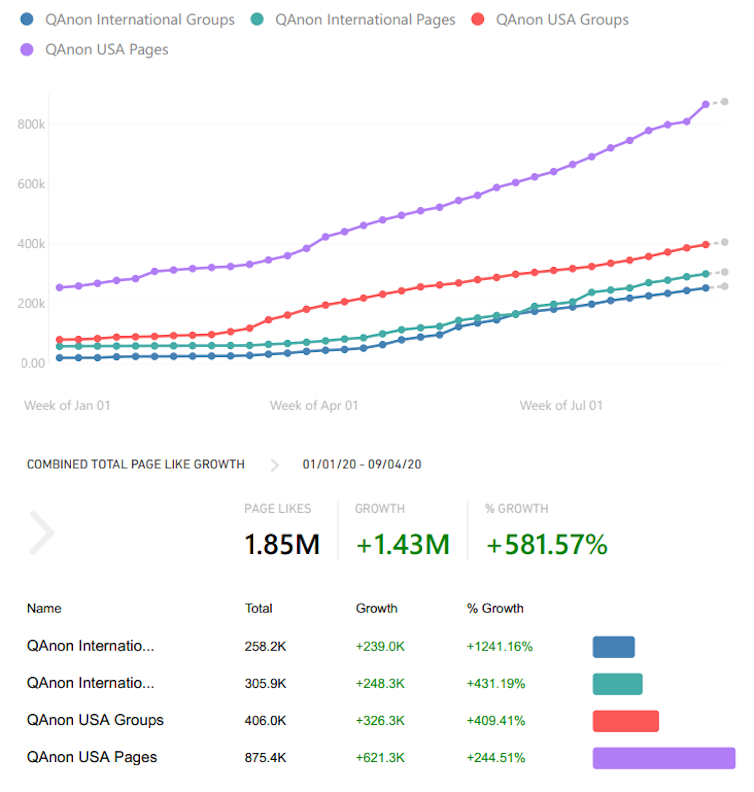

The COVID-19 pandemic has played a signficant role in popularizing the QAnon movement. Facebook data since the start of 2020 shows QAnon membership grew by 581 per cent — most of which occurred after the United States closed its borders last March as part of its coronavirus containment strategy.

As social media researcher Alex Kaplan noted, 2020 was the year “QAnon became all of our problem” as the movement initially gained traction by spreading COVID-related conspiracy theories and disinformation and was then further mainstreamed by 97 U.S. congressional candidates who publicly showed support for QAnon.

Crowdsourced answers

The essence of QAnon lies in its attempts to delineate and explain evil. It’s about theodicy, not secular evidence. QAnon offers its adherents comfort in an uncertain — and unprecedented — age as the movement crowdsources answers to the inexplicable.

QAnon becomes the master narrative capable of simply explaining various complex events. The result is a worldview characterized by a sharp distinction between the realms of good and evil that is non-falsifiable.

No matter how much evidence journalists, academics and civil society offer as a counter to the claims promoted by the movement, belief in QAnon as the source of truth is a matter of faith — specifically in their faith in Trump and “Q,” the anonymous person who began the movement in 2017 by posting a series of wild theories about the Deep State.

Trump validated theories

The year 2020 was also Trump finally gave QAnon what it always wanted: respect. As Travis View, a conspiracy theory researcher and host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast recently wrote: “Over the past few months …Trump has recognized the QAnon community in a way its followers could have only fantasized about when I began tracking the movement’s growth over two years ago.”

Trump, lawyers Sidney Powell and Lin Wood, and QAnon “rising star” Ron Watkins have all been actively inflaming QAnon apocalyptic and anti-establishment desires by promoting voter fraud conspiracy theories.

Doubts about the validity of the election have been circulating in far-right as well as QAnon circles. Last October, I wrote that if there were delays or other complications in the final result of the presidential contest, it would likely feed into a pre-existing belief in the invalidity of the election — and foster a chaotic environment that could lead to violence.

Hope for miracles

The storming of U.S. Capitol saw the culmination of what has been building up for weeks: the “hopeium” in QAnon circles that some miracle via Vice-President Mike Pence and other constitutional witchcraft would overturn the election results.

Instead, QAnon followers are now faced with the end of a Trump presidency — where they had free reign — and the fear of what a Biden presidency will bring.

We have now long passed the point of simply asking: how can people believe in QAnon when so many of its claims fly in the face of facts? The attack on the Capitol showed the real dangers of QAnon adherents.

Their militant and anti-establishment ideology — rooted in a quasi-apocalyptic desire to destroy the existing, corrupt world and usher in a promised golden age — was on full display for the whole world to see. Who could miss the shirtless man wearing a fur hat, known as the QAnon Shaman, leading the charge into the Capitol rotunda?

What will happen now? QAnon, along with other far-right actors, will likely continue to come together to achieve their insurrection goals. This could lead to a continuation of QAnon-inspired violence as the movement’s ideology continues to grow in American culture.

Marc-André Argentino, PhD candidate Individualized Program, 2020-2021 Public Scholar, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

QAnon and the storm of the U.S. Capitol: The offline effect of online conspiracy theories

Thursday, 07 January 2021 13:08 Written by theconversation

Marc-André Argentino, Concordia University

What is the cost of propaganda, misinformation and conspiracy theories? Democracy and public safety, to name just two things. The United States has received a stark lesson on how online propaganda and misinformation have an offline impact.

For weeks, Donald Trump has falsely claimed the November presidential election was rigged and that’s why he wasn’t re-elected. The president’s words have mirrored and fed conspriacy theories spred by followers of the QAnon movement.

While conspiracy theorists are often dismissed as “crazy people on social media,” QAnon adherents were among the individuals at the front line of the storming of Capitol Hill.

QAnon is a decentralized, ideologically motivated and violent extemist movement rooted in an unfounded conspiracy theory that a global “Deep State” cabal of satanic pedophile elites is responsible for all the evil in the world. Adherents of QAnon also believe that this same cabal is seeking to bring down Trump, whom they see as the world’s only hope in defeating it.

The evolution of QAnon

Though it started as a series of conspiracy theories and false predictions, over the past three years QAnon has evolved into an extremist religio-political ideology.

I’ve been studying the movement for more than two years. QAnon is what I call a hyper-real religion. QAnon takes popular cultural artifacts and integrates them into an ideological framework.

QAnon has been a security threat in the making for the past three years.

The COVID-19 pandemic has played a signficant role in popularizing the QAnon movement. Facebook data since the start of 2020 shows QAnon membership grew by 581 per cent — most of which occurred after the United States closed its borders last March as part of its coronavirus containment strategy.

As social media researcher Alex Kaplan noted, 2020 was the year “QAnon became all of our problem” as the movement initially gained traction by spreading COVID-related conspiracy theories and disinformation and was then further mainstreamed by 97 U.S. congressional candidates who publicly showed support for QAnon.

Crowdsourced answers

The essence of QAnon lies in its attempts to delineate and explain evil. It’s about theodicy, not secular evidence. QAnon offers its adherents comfort in an uncertain — and unprecedented — age as the movement crowdsources answers to the inexplicable.

QAnon becomes the master narrative capable of simply explaining various complex events. The result is a worldview characterized by a sharp distinction between the realms of good and evil that is non-falsifiable.

No matter how much evidence journalists, academics and civil society offer as a counter to the claims promoted by the movement, belief in QAnon as the source of truth is a matter of faith — specifically in their faith in Trump and “Q,” the anonymous person who began the movement in 2017 by posting a series of wild theories about the Deep State.

Trump validated theories

The year 2020 was also Trump finally gave QAnon what it always wanted: respect. As Travis View, a conspiracy theory researcher and host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast recently wrote: “Over the past few months …Trump has recognized the QAnon community in a way its followers could have only fantasized about when I began tracking the movement’s growth over two years ago.”

Trump, lawyers Sidney Powell and Lin Wood, and QAnon “rising star” Ron Watkins have all been actively inflaming QAnon apocalyptic and anti-establishment desires by promoting voter fraud conspiracy theories.

Doubts about the validity of the election have been circulating in far-right as well as QAnon circles. Last October, I wrote that if there were delays or other complications in the final result of the presidential contest, it would likely feed into a pre-existing belief in the invalidity of the election — and foster a chaotic environment that could lead to violence.

Hope for miracles

The storming of U.S. Capitol saw the culmination of what has been building up for weeks: the “hopeium” in QAnon circles that some miracle via Vice-President Mike Pence and other constitutional witchcraft would overturn the election results.

Instead, QAnon followers are now faced with the end of a Trump presidency — where they had free reign — and the fear of what a Biden presidency will bring.

We have now long passed the point of simply asking: how can people believe in QAnon when so many of its claims fly in the face of facts? The attack on the Capitol showed the real dangers of QAnon adherents.

Their militant and anti-establishment ideology — rooted in a quasi-apocalyptic desire to destroy the existing, corrupt world and usher in a promised golden age — was on full display for the whole world to see. Who could miss the shirtless man wearing a fur hat, known as the QAnon Shaman, leading the charge into the Capitol rotunda?

What will happen now? QAnon, along with other far-right actors, will likely continue to come together to achieve their insurrection goals. This could lead to a continuation of QAnon-inspired violence as the movement’s ideology continues to grow in American culture.

Marc-André Argentino, PhD candidate Individualized Program, 2020-2021 Public Scholar, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sowore: Nigeria presenting itself poorly to Biden – Ex-US envoy, Campbell

Thursday, 07 January 2021 05:25 Written by dailypostJohn Campbell, a former United States Ambassador to Nigeria, has criticised the arrest of Sahara Reporters Publisher, Omoyele Sowore.

Sowore and four others were put on remand at the Kuje Correctional Centre by an Abuja Magistrates’ Court.

In his reaction, Campbell told the Nigerian authorities that the arrest puts the country in a bad light.

The senior fellow for Africa at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington hinted that the coming government in America was taking notes.

“The arrest of Nigerian journalist and human rights activist Omoyele Sowore is a poor representation of Nigeria to the incoming Biden administration”, Campbell tweeted.

The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project has written to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention in protest of the detention.

SERAP urged the UN group to pressure President Muhammadu Buhari’s government to release the detainees.

In late 2019, Campbell likened the Buhari administration to military rule.

This followed Sowore’s re-arrest at the Federal High Court in Abuja on December 6 of the same year, and The Punch newspaper’s declaration that the Nigeria leader was a Major General not a President.

In an article titled: “Buhari’s Dictatorial Past and the Rule of Law Today in Nigeria”, Campbell stated that the Department of State Service’s (DSS) action had damaged the country’s international reputation.

He noted that in the immediate aftermath of the DSS’s “invasion of an Abuja court room and its re-arrest of Sowore, The Punch announced that it will prefix President Muhammadu Buhari’s name with his military rank, Major General, and will refer to his administration as a “regime,” until “they purge themselves of their insufferable contempt for the rule of law.”

According to Campbell, “The Punch draws parallels between Buhari’s government and his “ham-fisted military junta in 1984/85,” when he was military chief of state. For Punch the “regime’s actions and assaults on the courts, disobedience of court orders and arbitrary detention of citizens reflect the true character of the martial culture.”

He added that the newspaper also attacked the military and the police for failing to understand that peaceful agitation and the right to associate are fundamental rights.

Campbell said The Punch referred to the detention of Islamic Movement of Nigeria leader, Ibrahim el-Zakzaky, his wife, and former National Security Adviser, Sambo Dasuki, all in violation of various court orders, as well as governors’ moves to curtail media freedom and the right to demonstrate.

“Its criticism of Buhari is not surprising, but it is worth noting that Zakzaky and Dasuki are both northern Muslims. What is different this time is the parallelism between military rule and Buhari’s civilian administration. Buhari’s supporters are likely to find the Punch stance infuriating.

“Nigeria’s foreign friends will be hoping that the government takes no move to limit Punch’s freedom of expression. The SSS assault on a court room and the re-arrest of Sowore has already damaged the country’s international reputation”, Campbell stressed.

Washington: Curfew as Trump supporters protest after “never to concede” vow [Video]

Thursday, 07 January 2021 05:05 Written by dailypostWashington, D.C. will be under curfew from 6pm on Wednesday as authorities try to control President Donald Trump supporters clash with police.

The protesters charged up the steps of the U.S. Capitol as Congress debated the presidential vote count.

Muriel Bowser, Mayor of the United Stated capital, announced that the restriction will be in effect until 6 a.m. Thursday.

“No person, other than persons designated by the Mayor, shall walk, bike, run, loiter, stand, or motor by car or other mode of transport upon any street, alley, park, or other public place within the District,” a statement read.

The order will not apply to essential workers and media personnel on duty or traveling to or from work.

The demonstration started after Trump addressed his supporters vowing “never to concede” the election.

U.S. Capitol Police have ordered the Capitol locked down.

There were evacuations of the Library of Congress James Madison Memorial Building and the Cannon House Office Building.

The demonstration started after Trump addressed his followers vowing “never to concede” the election.

Also on Wednesday, Vice President Mike Pence rejected Trump’s call to him to block Congress’s confirmation of Biden as the next President.

Biden won the Electoral College by 306-232, and secured more than 80 million popular votes.

Video:

Popular News

Mike Pence rejects Trump’s demand to annul Biden’s victory

Thursday, 07 January 2021 04:33 Written by dailypostUnited States Vice President Mike Pence, on Wednesday, turned down President Donald Trump’s request regarding the November 3 election Joe Biden won.

Trump had asked Pence to try to block Congress’s confirmation of Biden as the next President.

The former Senator won the Electoral College by 306-232.

He also made history as the first presidential challenger to win more than 80 million popular votes.

CNBC reports that in a letter, Pence stressed that he lacks sole power to reject Electoral College votes for a candidate.

“It is my considered judgement that my oath to support and defend the Constitution constrains me from claiming unilateral authority to determine which electoral votes should be counted and which should not,” Pence wrote.

The VP said given the controversy surrounding the poll, some approach this year’s quadrennial tradition with great expectation, and others with dismissive disdain.

“Some believe that as Vice President, I should be able to accept or reject electoral votes unilaterally. Others believe that electoral votes should never be challenged in a Joint Session of Congress.”

Pence added that after a careful study of the U.S. Constitution, laws, and history, he believes neither view is correct.

About the same time the letter was released, Trump, outside the White House, insisted that Pence can overturn Biden’s election.

“Mike Pence, I hope you’re gonna stand up for the good of our Constitution and for the good of our country, and if you’re not I’m gonna be very disappointed in you, I will tell you right now,” he said.

The American leader Trump has not changed his position; that Biden did not defeat him.

Once Donald Trump is out of the White House, Americans should write him out of history too

Tuesday, 05 January 2021 23:21 Written by theconversationSince the US presidential election on November 3 2020, Donald Trump’s attempts to overturn the result and deny president-elect Joe Biden his victory have grown ever more desperate. Most recently a recording of a phone call to the secretary of the state of Georgia, Brad Raffensperger, on January 2, has revealed that Trump pressured Raffensperger to “find” more than 11,000 votes to tip the state’s result his way.

The call, which was published by the Washington Post, prompted senior Biden adviser Bob Bauer to remark: “We now have irrefutable proof of a president pressuring and threatening an official of his own party to get him to rescind a state’s lawful, certified vote count and fabricate another in its place.”

Concern at Trump’s refusal to concede the election, meanwhile, has led ten former defence secretaries to publish a letter in the Washington Post warning Trump against using the military in a last-ditch attempt to retain power.

A line has been crossed, perhaps into sedition. It seems unthinkable, but an American president is threatening the peaceful transfer of power – the cornerstone of any democracy. It seems inevitable that he will go, but then America will be forced to deal with the question: what to do with former President Trump?

The central tenet of republican philosophy and government is liberty – of the country as a whole and of the citizens individually. One is free only when one is free from arbitrary interference from the state or private persons. This is possible only when the powerful are constrained by the rule of law and are accountable to the people.

For all his talk of freedom, this is something Trump and his followers appear to have misunderstood. Is it that they think liberty is simply the right to do what they want? This is what seems evident in Trump’s willingness to discard the votes of millions of Americans in order to cling to power and then claim that that is democracy. This is the sort of hypocritical double-think that kills republics.

It seems unlikely that Biden will prosecute Trump – the president-elect and his team have been stressing the importance of healing and unity. But there must be consequences for Mr. Trump.

Vanishing act

What should they be? We can look to American history for the answer. When people think of malfeasance in the Oval Office, their minds probably turn to former president Richard Nixon, who after his resignation and pardon in 1974 spent some time as a social and political pariah. But Nixon is not the right parallel, in no small part because he fell on his own sword. Trump will never do this.

The better comparison is Benedict Arnold, the arch-traitor of the American Revolution. Before turning his coat for the British, Arnold fought gallantly for the Americans, especially at Saratoga. There are two memorials to him on that battlefield. One is of a boot, commemorating the spot where Arnold received a terrible wound to his leg. It describes him as the “most brilliant” soldier in the army, but does not name him.

The second memorial is the Saratoga Monument, where four niches commemorate the American commanders, but Arnold’s stands empty. He is not erased from history – like the Old Bolsheviks in Stalin’s Russia – but he is known through his absence, which stands as a warning.

You might think that writing a public figure out of history is not in keeping with American tradition. After all, the architects of the Confederacy have enjoyed public commemoration. Yet, these statues, mostly erected during the Jim Crow era as a way to strengthen segregation against the challenge of the civil rights movement, are being swept away. Someone like Robert E. Lee may have been an admirable general and “Southern gentleman”, but he took arms against his own country in defence of slavery. Many Americans feel that he does not merit a public memorial.

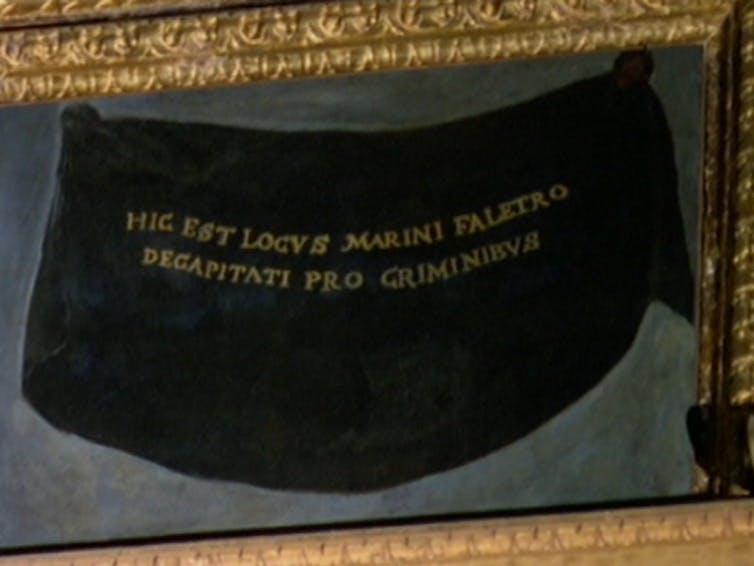

This is not uniquely American either. In Venice, the Great Council Chamber of the Palazzo Ducale is lined with portraits of the doges of that city’s great republic, a position comparable to the American presidency. However, one portrait is simply a black shroud.

This commemorates Marino Faliero, who plotted to overthrow the republic and establish a dictatorship. He was beheaded for treason, but death was not enough. He was condemned to damnatio memoriae, a practice that scrubs the memory of someone from society. The citizen who tries to destroy the republic has no place in the public memory of the state except by their absence.

Empty niche

Trump’s refusal to concede, the intimidation of governors, senators and other public officials, and his flirtation with sedition makes denying Trump the usual honours an appropriate punishment. It doesn’t mean he ought to be consigned to some Orwellian memory hole. He should still appear in textbooks and histories, but all the public commemoration that former presidents receive through custom should not be granted to him.

He should lose the honorific of “President” and should not be invited to official functions with other former presidents. There should be no portrait in the White House or any other public building, no military base or warship named in his honour, no presidential library. These honours should be stripped from him for the damage he has done to democracy, the rule of law and, ultimately, the freedom of every American citizen.

This is the fate that ought to await President Trump: to be an empty niche in the hall of presidents is the most fitting punishment for a man who valued his own ego and self-glorification over the stability and freedom of the republic that he swore to serve. Of course, given that more than 74 million Americans voted for him in 2020 makes this an unlikely prospect.![]()

Gwilym David Blunt, Lecturer in International Politics, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Reports: Trump preparing to flee to Scotland before Biden’s inauguration

Tuesday, 05 January 2021 14:58 Written by PM NEWSUnusual activity and surveillance near outgoing President Donald Trump’s golf resort in Turnberry, Scotland have triggered rumours that he might be fleeing there before Joe Biden’s inauguration.

As reported by Scotland’s weekly Sunday Post, Prestwick airport, which is near Trump’s Turnberry resort, was told to expect the arrival on Jan. 19 of a U.S. military Boeing 757 plane Trump has reportedly used before.

“There is a booking for an American military version of the Boeing 757 on Jan. 19, the day before the inauguration,” a source with Prestwick airport told the Post.

Trump playing golf in Turnberry in 2018. Credit: Photo by Peter Morrison/AP

“That’s one that’s normally used by the vice president but often used by the first lady. Presidential flights tend to get booked far in advance, because of the work that has to be done around it.”

Several U.S. Army aircraft have been seen performing surveillance above Trump’s flagship golf resort starting Nov. 12, several days after Biden was projected as the winner of the presidential election.

“The survey aircraft was based at Prestwick for about a week,” an airport source said.

“It is usually a sign Trump is going to be somewhere for an extended period.”

Some media outlets in the US have speculated that Trump would announce a 2024 re-election bid during a flight on one of the President’s official Air Force One planes on inauguration day.

Veteran NBC reporter Ken Dilanian tweeted: “Trump may announce for 2024 on inauguration day.

“Either way, he won’t attend the inauguration and does not plan to invite Biden to the White House or even call him.”

White House spokesman Judd Deere said Trump has not finalised his plans for inauguration day.

Trump asks Georgia SoS to alter November election result, phone call leaks

Monday, 04 January 2021 01:05 Written by PM NEWSOutgoing U.S. President Donald Trump urged fellow Republican Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia secretary of state, to alter the certified result of the November election so that he will emerge the winner.

In the extra-ordinary one hour phone call, published by Washington Post, Trump asked Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to overturn his defeat.

The call was made on Saturday.

Listen to the whole conversation:

Election experts said the call raised legal questions.

The Washington Post obtained a recording of the conversation in which Trump alternately berated Raffensperger, tried to flatter him, begged him to act and threatened him with vague criminal consequences if the secretary of state refused to pursue Trump’s false claims, at one point warning that Raffensperger was taking “a big risk.”

Throughout the call, Raffensperger and his office’s general counsel rejected Trump’s assertions, explaining that the president is relying on debunked conspiracy theories and that President-elect Joe Biden’s 11,779-vote victory in Georgia was fair and accurate.

Trump dismissed their arguments.

“The people of Georgia are angry, the people in the country are angry,” he said. “And there’s nothing wrong with saying, you know, um, that you’ve recalculated.”

Raffensperger responded: “Well, Mr. President, the challenge that you have is, the data you have is wrong.”

At another point, Trump said: “So look. All I want to do is this. I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have. Because we won the state.”

The rambling and at times incoherent conversation offered a remarkable glimpse of how consumed and desperate the president remains about his loss, unwilling or unable to let the matter go and still believing he can reverse the results in enough battleground states to remain in office.

“There’s no way I lost Georgia,” Trump said, a phrase he repeated again and again on the call. “There’s no way. We won by hundreds of thousands of votes.”

Several of his allies were on the line as he spoke, including White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and conservative lawyer Cleta Mitchell, a prominent GOP lawyer whose involvement with Trump’s efforts had not been previously known.

In a statement, Mitchell said Raffensperger’s office “has made many statements over the past two months that are simply not correct and everyone involved with the efforts on behalf of the President’s election challenge has said the same thing: Show us your records on which you rely to make these statements that our numbers are wrong.”

The White House, the Trump campaign and Meadows did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Raffensperger’s office declined to comment.

On Sunday, Trump tweeted that he had spoken to Raffensperger, saying the secretary of state was “unwilling, or unable, to answer questions such as the “ballots under table” scam, ballot destruction, out of state “voters”, dead voters, and more. He has no clue!”

*Published by Washington Post